Barbara Leonard Reynolds facts for kids

Barbara Leonard Reynolds (born Barbara Dorrit Leonard; Milwaukee, Wisconsin, June 12, 1915 – February 11, 1990) was an American writer, Quaker, peace activist, and teacher.

In 1951, Barbara moved with her husband to Hiroshima, Japan. There, her husband studied how radiation affected children who survived the first atomic bomb. After this, Barbara and her family became strong peace activists. They even sailed around the world to protest nuclear weapons. In the early 1960s, she traveled globally with atomic bomb survivors. They wanted to show world leaders the terrible effects of nuclear war. Barbara then started the World Friendship Center, where she worked for 13 years. She also helped create the Hiroshima Nagasaki Memorial collection.

Later in her life, after 1978, she continued her work for peace and against nuclear weapons. In California, she helped people from Cambodia who were escaping war and danger.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Barbara Dorrit Leonard was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. She was the only child of Sterling Andrus Leonard and Minnetta Florence Sammis. Her father was an English professor and writer. Her mother was an educator who checked if new toys were safe for children. Barbara's grandmother, Eva Leonard, was also a writer for newspapers.

When Barbara was fifteen, her father died in a canoeing accident on Lake Mendota. He was with another professor, Dr. I. A. Richards. Their canoe turned over, and after two hours in the cold water, her father disappeared. Dr. Richards was rescued. This event was a big story in newspapers at the time.

In 1935, Barbara married Earle L. Reynolds. They had three children: Tim (born 1936), Ted (born 1938), and Jessica (born 1944). In 1951, Dr. Reynolds was sent to Hiroshima by the Atomic Energy Commission. His job was to study the effects of radiation on children who had survived the atomic bomb. Barbara and their children went with him. They lived near an army base. During their three years there, Earle built a 50-foot (15 m) yacht called the Phoenix of Hiroshima.

Sailing for Peace

In 1954, the Reynolds family sailed around the world in their yacht, the Phoenix of Hiroshima. In 1958, Barbara, Earle, Jessica, and a crew member named Niichi (Nick) Mikami arrived in Honolulu. They saw another yacht, the Golden Rule, which belonged to four Quaker men. These men had tried to protest American nuclear testing in the Pacific Ocean. They were arrested because the government had made a rule saying people couldn't enter the test area.

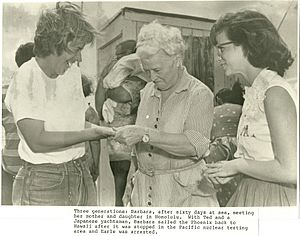

On July 2, 1958, the Reynolds family and Nick sailed the Phoenix into the nuclear test zone. The American Coast Guard stopped them. Dr. Reynolds, as the captain, was arrested. He was told to sail the Phoenix to Kwajalein. From there, he, Barbara, and Jessica were flown to Honolulu for Earle's trial. Barbara later flew back to Kwajalein to help Ted and Nick sail the yacht back to Hawaii. This trip took sixty days. After a long legal process, the family finished their trip around the world. Nick Mikami became the first Japanese person to sail around the world.

When they arrived back in Hiroshima, the family received a warm welcome. Many hibakusha (atomic bomb survivors) thanked them for protesting nuclear weapons. One woman showed Barbara her scars from the bomb and thanked her for speaking out. This made Barbara realize she needed to do more. She decided to speak out against nuclear weapons and work for disarmament.

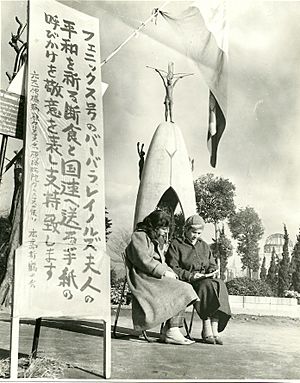

In 1961, to protest Soviet nuclear testing, the family sailed to Nakhodka, Russia. They were stopped by a Soviet Coast Guard boat. Barbara and her family had a two-hour talk about peace with the captain. Barbara wanted to give him hundreds of letters from Hiroshima and Nagasaki survivors, asking for peace. But he would not take them.

When they returned to Hiroshima, Barbara decided to bring a survivor from Hiroshima to deliver the letters personally to world leaders and the United Nations. She believed these survivors were like "prophets" for their time. A committee in Hiroshima chose two survivors: Miyoko Matsubara, a 29-year-old woman, and Hiromasa (Hiro) Hanabusa, an 18-year-old student who had lost his family in the bombing.

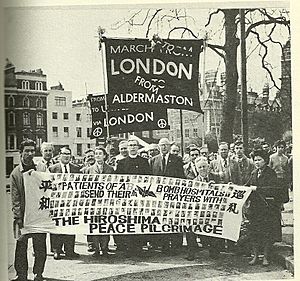

In 1962, Barbara organized the Peace Pilgrimage. She traveled with the two hibakusha around the world. They shared their personal stories of atomic war and asked world leaders to ban nuclear weapons. For over five months, they visited 13 countries, including the Soviet Union. They were welcomed by leaders, churches, schools, and the media. In the United States, they spoke to many groups and met with leaders in Washington D.C. and at the United Nations. They also attended a disarmament conference in Geneva.

Two years later, Barbara organized the World Peace Study Mission. She took 25 survivors from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, along with 15 interpreters, to every nuclear nation, including the Soviet Union. Teachers met with teachers, and doctors met with doctors. At the UN, they asked the U.S. government to return a film called Hiroshima – A Documentary of Atomic Bombing, which had been taken by the U.S. military. Dr. Tomin Harada, a doctor who cared for hibakusha, said that through Barbara's mission, the survivors were introduced to the world, and the anti-nuclear movement grew stronger.

World Friendship Center

Barbara wanted a place where visitors could stay and hear the stories of the survivors. In 1965, the World Friendship Center was opened. It helps connect hibakusha with people from around the world through peace efforts. Barbara was its first Director. Dr. Albert Schweitzer, a famous doctor, even became an honorary sponsor. Thousands of people have stayed at the center since it began.

Barbara spent 13 years getting to know the people who had lived through the bomb. Many lived in simple homes and felt self-conscious about their scars. They often faced discrimination. Barbara started "Hibakusha Handicrafts." She found people to teach survivors how to make small items like coin purses. She would then sell these items in the United States to help the survivors earn money. She also visited the Hiroshima A-Bomb Hospital, where survivors were still suffering from serious illnesses caused by radiation.

Barbara adopted Hiro Hanabusa, the orphan survivor she had traveled with on the Peace Pilgrimage. She helped him go to college in the United States. She also helped arrange a marriage for Hiro with the woman he loved. Hiro, who was an orphan, later had seven children.

In 1975, Barbara found a home for the 3,000 books and documents she had collected about Hiroshima, Nagasaki, nuclear weapons, and peace. This collection, called the Hiroshima Nagasaki Memorial Collection, was opened at Wilmington College in Ohio. It is the largest collection of materials about the bombings outside of Japan.

Later Life and Activism

In 1978, Barbara moved to Long Beach, California. She quickly became involved in helping Cambodian refugees who were escaping war and danger. She helped them find homes, jobs, and education, and gave them support.

During this time, she also worked to help a young Vietnamese woman named Mai Phuong Dao, who was badly injured. Dao had worked in an orphanage in Saigon. When American troops left, the orphanage became a military building. Dao, worried about five half-American orphans, took two of them into her own home, along with her own baby. When Dao and her children were finally allowed to come to America, Barbara let them live in her apartment.

Barbara believed it was wrong to pay taxes that supported war. So, she chose to live simply, below the poverty line, so she wouldn't owe taxes. She vowed not to have an easier life than the bomb survivors or the Cambodian refugees she helped.

Author

Barbara came from a family of writers. She, her husband Earle, all three of their children, and two of their grandchildren became published authors.

Barbara's books often reflected her family's adventures. After writing a mystery book called Alias for Death, she wrote books for each of her children. Pepper was about Tim and his raccoon. Hamlet and Brownswiggle was about Ted and his hamsters. Emily San was about an American girl living in Japan. She also wrote Cabin Boy and Extra Ballast about a brother and sister sailing with their family. After her family sailed around the world, Barbara co-wrote a non-fiction book for adults with her husband, called All in the Same Boat.

Awards and Recognition

For her work helping survivors and founding the World Friendship Center, Barbara received a key to the city of Hiroshima in 1969. In 1975, she was made an honorary citizen by Mayor Araki. She was the first woman and only the second American to receive this honor. The first was Norman Cousins, who raised money to bring 25 "Hiroshima Maidens" to the U.S. for surgery after their severe injuries from the atomic bomb.

In 1984, Barbara received one of 15 Wonder Woman awards. These awards honored women over 40 who were working to fix problems that people often ignored. The award organizers called them "role models for the next generation" and "living history."

Death and Legacy

Barbara died suddenly in Wilmington, Ohio, in 1990. Memorial services were held in Wilmington, Long Beach, Philadelphia, and Hiroshima. All major Japanese TV networks and newspapers covered her life and passing. Dr. Tomin Harada, the doctor who cared for Mai Phuong Dao, attended the service in California. He later wrote that Americans seemed not to have fully understood Barbara's importance, compared to the Japanese. When he returned to Hiroshima, he organized a memorial service for her there.

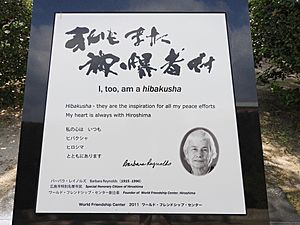

Survivors designed a monument to Barbara, which includes her statement, "I, too, am a hibakusha." This monument was revealed in the Hiroshima Peace Park (Ground Zero) on June 12, 2011, which would have been her 96th birthday.

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |