Battle of Kowloon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Kowloon |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First Opium War | |||||||

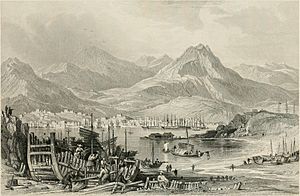

The Chinese fort in Kowloon, 1841 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Charles Elliot Henry Smith Joseph Douglas (WIA) |

Lai Enjue | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 4 boats1 | 3 junks 1 fort |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3 wounded | 2 killed 6 wounded |

||||||

| 1 1 cutter, 1 schooner, 1 pinnace, and 1 barge. | |||||||

The Battle of Kowloon was a small fight between British and Chinese ships. It happened near the Kowloon Peninsula in China on September 4, 1839. This area is now part of Hong Kong. This battle was the first armed conflict of the First Opium War.

The fight started because British boats tried to get food. The Chinese government had stopped selling food to the British community. This ban happened after a Chinese man died in a fight with British sailors. The Chinese authorities wanted the British to hand over the sailor responsible. But British officials handled the punishment themselves, which the Chinese did not think was enough. So, they cut off food supplies to pressure the British.

Captain Charles Elliot was the main British trade official in China. He sailed to Kowloon in his boat, the Louisa, to get food. He was joined by the Pearl and a small boat from HMS Volage. They met three Chinese war junks. Elliot sent an interpreter to ask for food. After hours of talks, Elliot gave an ultimatum: if they didn't get supplies, the junks would be attacked. When the time ran out, the British opened fire. The junks fired back, supported by a fort on shore. The Chinese junks chased the British boats when they ran low on ammunition. But the British reloaded and fought back. The Chinese then went back to their original spot, and the battle ended in a tie.

Why Did the Battle Happen?

On July 7, some British and American sailors landed in Kowloon. After some of them drank a local rice liquor, a local man named Lin Weixi was badly beaten in a fight. He died the next day.

Charles Elliot, the British trade official, offered rewards to find those responsible. He also gave money to Lin's family. However, the Chinese Imperial Commissioner Lin Zexu demanded that the British hand over the person who killed Lin. Elliot refused.

Instead, Elliot held a trial on a British ship. Two men were found guilty of rioting and three others of assault. They were fined and sentenced to work in England. But when they arrived in England, they were set free. This was because the trial held on the ship was later found not to have the right authority. Elliot had invited Chinese officials to watch the trial, but none came. Since no one was handed over to the Chinese, Lin Zexu was not happy. He felt that the British trial was an attack on China's power.

So, on August 15, Lin stopped all food sales to the British. Chinese workers helping the British in Macao also left. Chinese war junks appeared, and warnings were put up that water springs were poisoned. By the end of August, about 2,000 British people were stuck in Hong Kong harbor on over 60 ships. They had no fresh food or water. Captain Henry Smith arrived with his ship, the Volage. Elliot warned Chinese officials that trouble would happen if the food ban continued.

How the Battle Unfolded

On September 4, Elliot sailed to Kowloon in his boat, the Louisa, to get food. He was with the Pearl and a small boat from the Volage. They found three Chinese war junks anchored there, blocking food supplies. Elliot sent his interpreter, Karl Gutzlaff, to the largest junk. Gutzlaff carried messages from Elliot demanding food and asking them to stop poisoning water.

A Chinese spokesman said they couldn't allow food sales without orders from their superiors. Gutzlaff asked if they would starve while waiting for orders. They agreed that no one would want to starve. They then sent him to another junk where a naval officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Lai Enjue, was.

Gutzlaff kept going back and forth between the British and Chinese. He even offered money. The Chinese soldiers went to talk with an officer in a nearby fort. They said nothing could be done without permission from higher officials. Gutzlaff wrote a list of needed items. He was told they couldn't get them, but some items would be given for immediate needs. Gutzlaff believed this was just a trick to give the Chinese time to prepare their fort. He left, feeling frustrated.

After five or six hours of delays, Elliot sent a boat to a different part of the bay to buy food. They succeeded, but Chinese officials forced them to return the food. Elliot was very angry when he heard this. He then ordered his ships to open fire on the Chinese junks. This was the first armed conflict of the First Opium War.

A clerk named Adam Elmslie, who was there, said Elliot sent a warning at 2 pm. He said if they didn't get food in half an hour, they would sink the junks. When the time passed, Captain Smith ordered his small boat to fire. Elmslie wrote that the junks then fought back strongly, firing many guns. He noted that the Chinese shots were not aimed low enough, or else no one would have survived.

At 3:45 pm, shore cannons also started firing to help the junks. By 4:30 pm, the Louisa had fired many shots and was running low on ammunition. The British boats started to sail away. The junks, which were much larger, chased them.

After getting more ammunition, the British boats turned around and fought the junks again. Elmslie described the loud noise and chaos. He said the Chinese junks retreated back to where they started. More British boats arrived, but night fell, ending the fight. The next morning, the junks were empty. Elliot decided not to continue the fight since the Chinese were not causing more trouble.

In total, three British sailors were wounded. The Chinese reported two killed and six wounded.

What Happened After?

That evening, Elliot and Smith talked about destroying the Chinese junks and attacking the fort. But Smith agreed with Elliot not to do it. Elliot felt that an attack would harm the local village and its people. He wrote that he didn't want a British warship to kill Chinese sailors, even though his small boat could have done it. He felt he had done well by holding back.

Elliot put up a notice on shore that day. It said that the British wanted peace but would not be poisoned or starved. They didn't want to bother Chinese ships but insisted that people must be allowed to sell food.

An American sea captain, Robert Bennet Forbes, watched the battle from a distance. He called it "quite a farce" and stayed away from the fight.

After the battle, the British were able to get food supplies. However, the food was a bit more expensive. One historian, Arthur Waley, thought that Chinese patrol boats might have been trying to get unofficial payments from farmers. They would allow farmers to sell food during the ban if they paid. After the battle, the Chinese might have accepted smaller payments. This would have made food available again, but at a slightly higher price.

The Chinese commander, Lai, sent a report claiming victory. He said they sank a British ship and caused many casualties. This was one of several reports during the war where Chinese officials gave misleading information to the emperor. They often exaggerated their successes to get rewards or promotions. The emperor later found out that he had been systematically misled about events during the war.

Images for kids

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |