Benjamin Jesty facts for kids

Benjamin Jesty (born around 1736 – died 16 April 1816) was a farmer from Yetminster in Dorset, England. He is remembered for an important early experiment. He tried to protect people from smallpox by using a milder disease called cowpox.

In the late 1700s, many country people knew that if you caught cowpox, you wouldn't get smallpox. Cowpox was a much less serious illness. Jesty was one of the first people to purposely give someone cowpox to protect them. He did this in 1774. Other people in England, Denmark, and Germany also tried this between 1770 and 1791. Only Jobst Bose in Germany did something similar before Jesty, in 1769.

Edward Jenner, a doctor, is often given credit for creating the smallpox vaccine in 1796. However, Jesty did his work about 20 years earlier. Unlike Jenner, Jesty did not tell many people about his discovery.

Benjamin Jesty's Early Life

Benjamin Jesty was born in Yetminster, Dorset. He was baptized on 19 August 1736. He was the youngest of at least four sons. His father, Robert Jesty, was a butcher. We don't know much else about his early years.

In March 1770, he married Elizabeth Notley (1740–1824). They got married in Longburton, which is about four miles from Yetminster. The couple lived at Upbury Farm, near the Yetminster church. They had four sons and three daughters.

Jesty and the Smallpox Epidemic

In the 1700s, smallpox was a very common and dangerous disease in England. There were often epidemics, which are outbreaks of a disease that spread quickly. In farming areas, especially where dairy cows were kept, people noticed something interesting. Milkmaids and other farm workers who got cowpox from handling cows often did not catch smallpox. They could even care for smallpox patients without getting sick themselves.

This knowledge slowly spread among doctors. By 1765, some doctors were discussing how cowpox could prevent smallpox.

In 1774, a smallpox epidemic came to Yetminster. Benjamin Jesty, along with two of his servants, had already caught cowpox. Jesty decided to try and protect his wife, Elizabeth, and his two oldest sons. He wanted to give them immunity by infecting them with cowpox.

He took his family to a farm in nearby Chetnole. There was a cow there that had cowpox. Jesty used a darning needle to take some pus from the cow's sores. He then scratched his family's arms with the needle to transfer the material. His sons had only mild reactions and got better quickly. His wife's arm became very swollen and painful. For a while, people were worried about her, but she also recovered fully.

Jesty's neighbors were not happy about his experiment. They called him cruel and would shout at him and throw things when he went to market. People thought it was disgusting to put an animal disease into a human body. Some even feared that people would turn into horned beasts!

But Jesty's treatment worked. In the years that followed, his two older sons were exposed to smallpox. They did not catch the disease. This proved that Jesty's method was effective.

Interest in using cowpox to prevent smallpox grew. In May 1796, more than 20 years after Jesty's experiment, Edward Jenner began his own vaccination experiments. Around 1797, Jesty and his family moved to Downshay Manor Farm in Worth Matravers. Here, he met Dr. Andrew Bell, a local church leader. Dr. Bell was inspired by Jesty's work and vaccinated over 200 people in his area in 1806.

Later Recognition and Final Years

In June 1802, the House of Commons gave Edward Jenner £10,000 for his work on vaccination. He received another £20,000 in 1807. Before Jenner received his first award, a doctor named George Pearson told the House of Commons about Jesty's earlier work in 1774. This was 22 years before Jenner's experiments.

Unfortunately, Jesty did not ask for a reward himself. Also, Pearson included other people who claimed to have done similar work, but their stories could not be proven. So, Jesty did not receive any money.

Later, Dr. Andrew Bell, who knew Jesty, also tried to get him recognized. In 1803, Bell wrote a paper saying Jesty was the first person to use cowpox for protection. He sent copies to a medical institution and a politician.

In 1805, Jesty was invited to London by George Pearson and the institution. He gave his story to 12 medical officers. Robert, Jesty's oldest son (who was 28 at the time), also went to London. He agreed to be given smallpox again to show that he was still immune. After Jesty was questioned, he received a special award and a pair of gold medical tools called lancets. Their story was published in a medical journal.

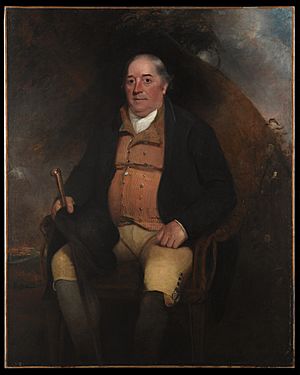

For his trip to London, Jesty's family wanted him to wear nicer clothes. But he refused, saying he saw no reason to dress better in London than at home. Right after his meeting, Jesty went to the studio of a portrait painter named Michael William Sharp. Jesty was not a patient person, so Mrs. Sharp played the piano to help calm him while the painting was done. This portrait is now owned by the Wellcome Trust. It is on loan to the Dorset County Museum in Dorchester.

On Sunday, 15 July 1806, Dr. Bell gave a sermon twice to honor Jesty. He reminded people about Jesty's discovery, which was often forgotten even though they knew about Dr. Jenner.

Benjamin Jesty died in Worth Matravers on 16 April 1816. He was buried in a special spot in the churchyard. His wife, Elizabeth, died on 8 January 1824 and was buried next to him. Their gravestones are now protected because of their historical importance.

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |