Great Molasses Flood facts for kids

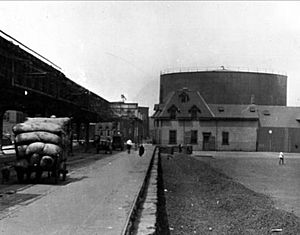

Wreckage of collapsed tank is visible in background, center, next to light-colored warehouse

|

|

| Date | January 15, 1919 |

|---|---|

| Time | approximately 12:30 pm |

| Location | Boston, Massachusetts |

| Cause | Cylinder stress failure |

| Deaths | 21 |

| Non-fatal injuries | 150 injured |

The Great Molasses Flood, also called the Boston Molasses Disaster, happened on January 15, 1919. It took place in the North End area of Boston, Massachusetts.

A huge storage tank filled with about 2.3 million US gal (8,700 m3) of molasses burst. This amount of molasses weighed around 13,000 short tons (12,000 t). A giant wave of molasses rushed through the streets. It moved at an estimated 35 mph (56 km/h). This terrible event killed 21 people and injured 150 others.

The disaster became a famous local story. For many years, people living in the area said it still smelled like molasses on warm summer days.

Contents

Cleaning Up After the Molasses Flood

After the flood, cleanup crews got to work. They used salt water from a fireboat to wash away the sticky molasses. They also used sand to soak it up. The nearby harbor turned brown with molasses and stayed that way until summer.

Cleaning the immediate area took many weeks. Hundreds of people helped with the effort. It took even longer to clean the rest of Boston and its suburbs. Rescue workers, cleanup crews, and even people just watching had tracked molasses everywhere. It spread to subway platforms and inside trains. It got on telephone handsets, in homes, and many other places. People said that "Everything that a Bostonian touched was sticky."

Why Did the Molasses Tank Burst?

Several things likely caused this disaster. One idea is that the tank might have leaked from the very first day it was filled in 1915.

The tank was also built poorly and not tested enough. Also, carbon dioxide gas might have built up inside. This gas is made when molasses ferments, like when sugar turns into alcohol. Warmer weather the day before the disaster could have made this pressure worse. The air temperature rose from 2 to 41 °F (−17 to 5.0 °C) during that time.

The tank broke from a manhole cover near its bottom. A small crack, called a fatigue crack, probably grew bigger over time until the tank failed.

After the disaster, an investigation looked into what happened. It found that Arthur Jell, who was in charge of building the tank, ignored important safety checks. For example, he didn't fill the tank with enough water to properly check for leaks. He also ignored warning signs, like loud groaning noises every time the tank was filled. He had no experience in building or engineering. When the tank was filled with molasses, it leaked so much that it was painted brown to hide the leaks. Local people even collected the leaked molasses for their homes.

In 2014, engineers studied the disaster using modern methods. They found that the steel used for the tank was only half as thick as it should have been. This was true even for the less strict building rules of that time. The steel also didn't have enough manganese, which made it more brittle and likely to break. The tank's rivets (metal fasteners) also seemed to be faulty. Cracks first appeared at the rivet holes.

In 2016, a team from Harvard University studied the disaster in detail. They used old newspaper articles, maps, and weather reports from 1919. The students also tested how cold corn syrup flowed in a small model of the neighborhood. They found that reports of the flood's high speed were likely true.

Two days before the disaster, warmer molasses was added to the tank. This made the molasses inside less thick. When the tank broke, the molasses cooled quickly as it spread. It reached Boston's cold winter temperatures, and its thickness increased a lot. The Harvard study concluded that the molasses cooled and thickened fast. This made it harder for rescuers to free victims before they suffocated.

The Area Today

United States Industrial Alcohol, the company that owned the tank, did not rebuild it. The land where the tank and a paving company once stood became a yard for the Boston Elevated Railway. This railway is now the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority.

Today, this spot is a city park called Langone Park. It has a Little League Baseball field, a playground, and bocce courts. Next to it is Puopolo Park, which has more recreational areas.

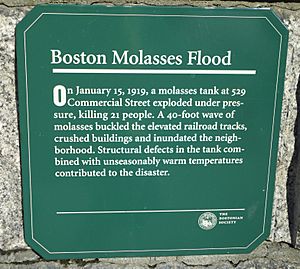

A small plaque at the entrance to Puopolo Park remembers the disaster. The Bostonian Society placed this plaque. It says:

On January 15, 1919, a molasses tank at 529 Commercial Street exploded under pressure, killing 21 people. A 40-foot wave of molasses buckled the elevated railroad tracks, crushed buildings and inundated the neighborhood. Structural defects in the tank combined with unseasonably warm temperatures contributed to the disaster.

The accident is now a big part of local history. Not just because of the damage, but also because of the sweet smell. This smell filled the North End for decades after the flood. A journalist named Edwards Park said, "The smell of molasses remained for decades a distinctive, unmistakable atmosphere of Boston."

On January 15, 2019, a ceremony was held for the 100th anniversary of the event. Ground-penetrating radar was used to find the exact spot of the tank from 1919. The concrete base of the tank is still there. It is about 20 inches (51 cm) below the surface of the baseball field at Langone Park. People at the ceremony stood in a circle marking the tank's edge. The names of the 21 people who died in the flood were read aloud.

Images for kids

-

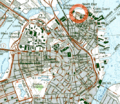

- Detail of molasses flood area:

- 1. Purity Distilling molasses tank

- 2. Firehouse 31 (heavy damage)

- 3. Paving department and police station

- 4. Purity offices (flattened)

- 5. Copps Hill Terrace

- 6. Boston Gas Light building (damaged)

- 7. Purity warehouse (mostly intact)

- 8. Residential area (site of flattened Clougherty house)

See also

In Spanish: Gran inundación de melaza de Boston para niños

In Spanish: Gran inundación de melaza de Boston para niños