Brilliant Pebbles facts for kids

Brilliant Pebbles was a special idea for protecting countries from long-range rockets. It was suggested in 1987, near the end of a time called the Cold War, when there was a lot of tension between big global powers. The plan was to have thousands of small satellites, called "pebbles," orbiting Earth. Each pebble would carry a small missile. These pebbles would fly over a country and, if long-range rockets were launched, they would use heat-seeking sensors to find them. Then, the pebbles would crash into these rockets before they could release their powerful explosives. This way, one pebble could stop many explosives at once.

Contents

What Were Brilliant Pebbles?

This system got its name from an earlier idea called "Smart Rocks." That idea involved large space stations with many small missiles. But building and launching so many big stations was very difficult. Scientists then thought about making the missiles themselves "smarter" and able to work on their own. This led to the idea of "Pebbles," which were much smaller and could act independently thanks to new sensors and tiny computers.

To hit rockets quickly, these independent pebbles would stay in continuous low Earth orbit near the edge of Earth's atmosphere. Being so low meant they could be attacked by special weapons designed to destroy satellites. However, it also meant they were less likely to create too much space debris, as they would naturally fall back into the atmosphere and be replaced regularly. Because they orbited so low, the pebbles had to travel very fast. This meant they couldn't stay over one spot. So, thousands of pebble satellites were needed, spread evenly around Earth, to make sure there were always enough in the right place.

Pebbles became the main design for the defense program. By 1991, it was ordered into production. At this time, the former large country was changing, and the main threat shifted to shorter-range rockets. The Pebbles design was changed, but this made it heavier and more expensive. The original plan for about 10,000 missiles was estimated to cost $10 to $20 billion. But by 1990, the cost for only 4,600 pebbles had grown to $55 billion. Debates in Congress in the early 1990s led to the cancellation of Pebbles in 1993. However, parts of the idea reappeared in later defense plans.

How Did the Idea Start?

Smart Rocks: The First Idea

The idea for a space defense system came from different places. Some say it was inspired by a movie. Others point to a talk about defense in 1967. A visit to a special control center in 1979 also played a part. There, leaders saw systems that could detect enemy rocket launches. But when asked what they could do, the answer was only to launch their own rockets back. This made leaders want a way to stop rockets instead of just reacting.

A military advisor named Daniel Graham suggested a new system based on an older idea called Project BAMBI. This new idea was "Smart Rocks." It involved "battle stations" orbiting close to Earth. Each station would have many small missiles, like those used by airplanes. These stations would have advanced sensors to find and track enemy long-range rockets as they launched. Then, they would fire their missiles. The missiles would guide themselves using heat sensors to hit the enemy rockets. Since rocket engines are very hot, even simple missiles could track them.

However, these small missiles had limited fuel. This meant they could only attack rockets close to their stations. To cover a large country, hundreds of stations were needed. But launching so many heavy stations was almost impossible with the technology at the time. Also, these stations would be easy targets for special weapons designed to attack satellites. It would be cheaper for an enemy to destroy the stations than for the US to build them.

Early Challenges and New Ideas

Around the same time, scientists at a lab called Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) were working on powerful laser weapons. They thought powerful explosive devices could create strong X-ray beams for long-range lasers. This project was called Project Excalibur. The idea was that one powerful explosive device could destroy many enemy rockets.

One of the scientists, Edward Teller, who worked on Excalibur, thought the Smart Rocks idea was not good. He suggested Excalibur instead. But Smart Rocks supporters pointed out that Excalibur weapons would destroy themselves when used. So, if an enemy attacked them, they would be destroyed anyway. Teller then suggested putting Excalibur weapons on missiles launched from submarines when needed.

Many of the early defense ideas faced problems. The Excalibur laser system failed important tests. Other ideas, like particle beam weapons, did not work well enough. Even the space-based laser needed to be much more powerful to stop a long-range rocket.

A group of scientists, the American Physical Society (APS), reviewed these energy-based weapons. Their report in 1987 said that none of the ideas were ready. They needed many more years of work and huge improvements to become useful.

The Birth of Brilliant Pebbles

After Excalibur failed its tests, scientists Teller and Lowell Wood looked for a new, more practical idea. They met with another physicist who noted that computers were becoming very small and powerful. This meant that the complex calculations needed for defense could now fit inside the missiles themselves. Also, new sensors could see targets clearly from far away and fit into a missile's nose.

This new design had a huge advantage: the interceptors (the pebbles) could fly on their own, without needing a large "garage" station. This meant an enemy could not easily destroy many interceptors at once. To attack the system, an enemy would need to launch a special weapon for every single pebble.

Wood started working on this idea. He combined new computer systems with advanced sensors. He realized that if a pebble hit a long-range rocket at very high speeds, the impact itself would be powerful enough to destroy the rocket, without needing an explosive warhead. He calculated that a practical pebble would weigh only a few kilograms.

To cover a large country, about 7,000 pebbles would be needed in orbit. This would ensure about 700 were always over the target area. If complete coverage was needed, up to 100,000 pebbles might be required. Each pebble was expected to cost around $100,000. Even a very large system might cost about $10 billion.

Launching these pebbles would be much cheaper than launching large battle stations. A single Space Shuttle could carry dozens, or even hundreds, of them. Some even thought about launching them from the ground using a special railgun. These lightweight pebbles would have a limited range, only able to attack targets directly in front of them. Larger pebbles with more fuel could attack more targets, meaning fewer would be needed overall.

By late 1987, Wood had detailed plans, a physical model, and computer simulations. He cleverly named this new, smaller, and smarter concept "Brilliant Pebbles."

Becoming a Key Defense Plan

Edward Teller helped Wood present the Brilliant Pebbles idea to important leaders in 1987. They were impressed and gave more money for studies. In March 1988, Teller and Wood showed a model of a pebble directly to President Reagan. Teller said the system would cost around $10 billion.

The Air Force also studied the idea and agreed that sensors could be placed directly on the missiles, making the system much simpler. For the next year, Wood and Teller strongly promoted Pebbles. However, there were concerns about the rising cost estimates. Initially, a pebble was estimated at $100,000, but by late 1988, this had increased to $500,000 to $1.5 million. There was also doubt if the sensors could be made small and cheap enough.

Changes and New Goals

When George H. W. Bush became president in 1989, the Cold War was ending. He ordered a review of all defense programs. This led to a decision to continue the defense program, with Brilliant Pebbles as a key part. Bush and Vice President Dan Quayle strongly supported Pebbles, noting its low cost and light weight.

A group of science advisors, the JASONs, reviewed Pebbles and found no major problems, though they worried about possible ways enemies could counter it. Another review by the Defense Science Board agreed.

A third review looked at how an enemy might try to stop Pebbles. It found some issues, but noted that these problems applied to any space-based system. A final Air Force report in 1989 compared Pebbles to older ideas and found Pebbles would be much cheaper, costing about $55 billion for 4,600 pebbles. This version of the system would also help detect launches.

The new plan for the defense system now relied on Brilliant Pebbles as its main design. Other parts of the original plan, like ground-based interceptor missiles and radars, remained.

Contracts were sent to companies to start building prototypes. Tests were planned, with early pebbles being tested on the ground and in space using small rockets. The goal was to have enough information by 1993 for the President to decide whether to build the full system.

Soon after, another review suggested that with the Cold War ending, the main threat was no longer a massive attack. Instead, it was shorter-range rockets that could threaten troops overseas. The report suggested modifying Pebbles to defend against these new threats.

This new idea was called "Protection Against Limited missile Strikes," or PALS. For Pebbles to work against shorter-range rockets, they would need much better sensors to track missiles even after their engines stopped firing.

The Gulf War then broke out, and the scenario of troops being attacked by short-range missiles came true. News showed images of missiles being intercepted. This made leaders in Congress, who were once doubtful, much more supportive of defense systems like PALS.

In January 1991, President Bush announced that the defense program would focus on "Global PALS," or GPALS. This meant protecting against limited rocket strikes from any source, whether against the United States, its forces overseas, or its allies. With this change, the number of pebbles needed was reduced to between 750 and 1,000.

The End of the Program

The GPALS plan was detailed in a May 1991 report. It consisted of four parts: a ground-based missile system to protect the United States, a ground- and sea-based system to defend overseas United States forces and allies, Brilliant Pebbles in space, and a command and control system tying them all together. Brilliant Pebbles was meant to detect launches early and attack any rocket with a range greater than 600 kilometers.

To get money for the system, the plan went to Congress. This led to the Missile Defense Act of 1991. This act supported funding for Brilliant Pebbles. However, it also said that the immediate goal was a smaller defense system by 1996 that would follow existing treaties. This meant Brilliant Pebbles would not be part of this first system.

Despite this, the director of the defense program, Henry F. Cooper, continued to prioritize Pebbles. In June 1991, contracts were given to companies to develop Brilliant Pebbles. This was the first time since the 1960s that a missile defense system was funded for production.

However, some politicians, like Senator Sam Nunn, criticized the focus on Pebbles. They argued that too much money was going to Pebbles, which wouldn't be ready by 1996. Cooper defended his choices, but eventually, $2 billion was moved from Pebbles to ground-based systems. The program faced more challenges when a Pebbles test failed in October 1992, as the rocket booster broke apart after launch.

In November 1992, Pebbles was removed from production contracts and sent back to being a research program. Its management was transferred to the Air Force. The contracts in January 1993 were for "advanced technology demonstration" instead of building a system for use.

When Bill Clinton became president in 1993, his new Secretary of Defense, Les Aspin, further reduced the budget for Pebbles. On February 2, 1993, he lowered its budget and moved it to a "follow on technology" category. In March 1993, it was renamed the Advanced Interceptor Technology Program. Finally, on December 1, 1993, the program was stopped. Brilliant Pebbles was no longer being developed.

How a Brilliant Pebble Worked

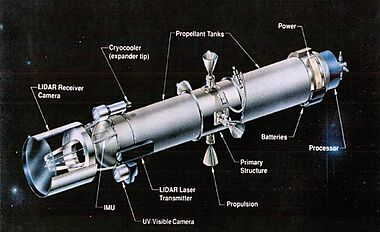

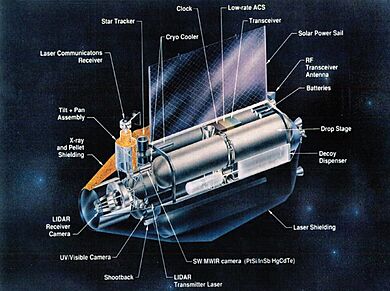

The final design of a pebble looked like a small missile, but it wasn't designed to fly through the air. It was about 3 feet long. Most of its body held fuel tanks for steering. At the very front, it had a special laser receiver and a laser to light up targets, along with a camera. Batteries were at the back. To move forward, it used four booster stages, each with its own fuel tank and engine.

For most of its time in space, a pebble would stay inside a "life jacket." This jacket gave it electricity from a solar panel, helped it know its position using a star tracker, and allowed it to communicate using lasers. The jacket also protected the pebble from laser attacks and small pellets from enemy anti-satellite weapons.

Testing the Pebbles

Only three full tests of the Brilliant Pebbles concept happened before the program was stopped. All three tests failed for different reasons.

The first test was on August 25, 1990. A pebble was launched into space. It was supposed to separate from its rocket and use its sensors to track the rocket's third stage. But an explosive bolt fired too early, causing part of the rocket to break and pull the pebble out. Only a separate experiment on another satellite successfully tracked the rocket. This failure delayed future tests.

The second test was on April 17, 1991. This time, the pebble was supposed to look down at a target against the bright Earth. But because of the first failure, they repeated the simpler nighttime test. The pebble was supposed to separate, turn, and then track its launcher. It failed to find the target, and its movements were not accurate enough. Its internal sensors also had problems.

The final test was on October 22, 1992. This used a more advanced, smaller prototype. The pebble and its target were launched from the same rocket. The pebble was supposed to track the target and get very close to it. But just seconds after launch, pieces started falling off the rocket booster. It was destroyed by safety officers. The problem was a failure in one of the rocket's engines.

Why Were Pebbles Special?

Cost-Effectiveness

Older missile defense systems had a problem: they cost more to build than the enemy's rockets they were supposed to stop. This meant an enemy could simply build more rockets to overcome the defense. This was called the "cost-exchange ratio." For a defense system to be successful, it needed to be cheaper to add to the defense than for the enemy to add to their attack.

Brilliant Pebbles seemed to solve this. Since each pebble flew on its own, an enemy would need to launch a special weapon for every single pebble they wanted to destroy. This would be very expensive for them, especially for a country with a weaker economy. So, it seemed like the enemy couldn't just build more rockets or anti-satellite weapons to defeat Pebbles cheaply.

The "Absentee Ratio" Challenge

However, critics pointed out a key issue: the "absentee ratio." A pebble could only attack a rocket if it was in the right place at the right time. So, adding just one enemy rocket didn't mean you needed one more pebble. You needed many more pebbles to ensure one was always in the right area. For Pebbles, this ratio was about 10 to 1. This meant adding one enemy rocket would require ten new pebbles, making the defense much more expensive.

Also, for pebbles to hit rockets during their "boost phase" (when their engines are firing), they had to reach the target very quickly. Some rockets could burn their engines for only a few minutes. If an enemy built rockets that burned even faster, they could release their explosives in as little as one minute. To catch such fast rockets, many dozens of pebbles would be needed for each one, making the defense extremely costly.

Some argued that this would lead to an "arms buildup," where both sides kept making more weapons, which was the opposite of what the defense system was supposed to achieve.

Other Problems

Another concern was that existing enemy defense systems could be used to attack the pebbles. By timing an attack just before launching their own rockets, an enemy could destroy pebbles approaching their country, creating a temporary "hole" for their rockets to fly through. Because of the absentee ratio, countering this would require adding many more pebbles, making it very expensive for the defense.

Finally, there was a technical issue with all space-based weapons. Since the late 1970s, some countries had used ground-based lasers to temporarily blind satellites. The energy needed to do this was much less than what was needed to destroy a missile. This meant that even if a powerful laser weapon couldn't destroy a rocket, a weaker laser could blind the sensors of a defense system like Pebbles. Such a system could make the pebbles useless for a short but critical time while enemy rockets were launched.

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |