Cache replacement policies facts for kids

In computing, cache replacement policies (also called cache algorithms) are smart rules or algorithms that a computer program or hardware uses to manage a cache. A cache is like a small, super-fast storage area for information. It helps your computer work faster by keeping data you use often or just used very recently in a place that's quicker to get to than regular memory.

When this fast storage (the cache) gets full, the computer needs to decide which old information to throw out to make space for new stuff. That's where cache replacement policies come in! They help the computer choose the best items to remove so that the most important or most likely-to-be-used data stays in the cache.

Contents

- How Caches Work: Hits and Speed

- Different Ways to Replace Data

- See also

How Caches Work: Hits and Speed

There are two main things that show how well a cache is working:

- Hit Ratio: This tells you how often the computer finds the information it's looking for already in the cache. A higher hit ratio means the cache is doing a great job, and the computer doesn't have to go to slower memory as often.

- Latency: This is how quickly the cache can give you the information once you ask for it (if it's there). Faster policies usually don't keep track of as much information, which makes them quicker.

Every cache policy tries to find a good balance between getting a high hit ratio and having low latency (being fast).

Sometimes, certain types of data, like video or audio streams, don't work well with caches. This is because each piece of data is usually read only once and then never needed again. This can sometimes fill up the cache with useless data, pushing out important information. This is called "cache pollution."

Other things to think about when managing a cache:

- Cost of items: Some data is harder or slower to get than others. The cache might want to keep the "expensive" items longer.

- Size of items: If data pieces have different sizes, the cache might remove one large item to fit several smaller ones.

- Expiring items: Some information, like news updates or website data, might have an "expiration date." The cache will remove these when they are no longer fresh.

Different Ways to Replace Data

There are many different policies (or algorithms) for deciding what to remove from a cache. Here are some of the most common ones:

Bélády's Algorithm: The Perfect (But Impossible) Way

The absolute best way to manage a cache would be to always remove the information that won't be needed for the longest time in the future. This perfect method is called Bélády's optimal algorithm.

Imagine your computer knows exactly what you'll click on next! It would keep only the files you're about to use. But since computers can't actually predict the future, this algorithm can't be used in real life. It's mostly used to compare how good other, real-world algorithms are.

Random Replacement (RR)

This is the simplest policy. When the cache is full, it just picks a random piece of data and throws it out to make space. It doesn't keep track of how often or when data was used. Because it's so simple, it's very fast.

Simple Queue-Based Policies

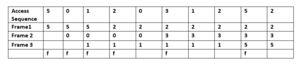

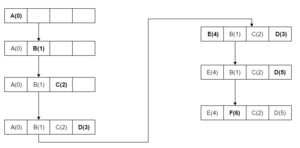

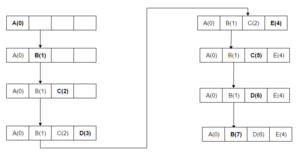

First In, First Out (FIFO)

Think of a line at a theme park ride. The first person to get in line is the first person to get on the ride. In a cache, the data that was put into the cache first is the first to be removed when space is needed. It doesn't matter if that data is used a lot.

Last In, First Out (LIFO)

This is the opposite of FIFO. Imagine a stack of plates. You always take the top plate (the last one put on). In a cache, the data that was added most recently is the first to be removed.

Simple Recency-Based Policies

Least Recently Used (LRU)

This policy removes the data that hasn't been used for the longest time. It's like cleaning out your closet and getting rid of clothes you haven't worn in ages.

To do this, the computer has to keep track of when every piece of data was last used. This can be a bit complicated and slow for very large caches.

Time Aware Least Recently Used (TLRU)

TLRU is a special version of LRU for situations where cached content has a limited "lifespan," like news articles that go out of date. It adds a "Time to Use" (TTU) value to content. This helps the cache decide to remove older, less popular content first, even if it was recently used. It's often used in network caches, like those that help deliver videos quickly.

Most Recently Used (MRU)

This policy is the opposite of LRU. It removes the data that was used *most recently*. This might sound strange, but it can be useful in specific situations. For example, if you're repeatedly scanning a very large file, the data you just read might not be needed again for a long time. In such cases, keeping the older data makes more sense.

LRU Approximations

Because keeping perfect track of LRU can be expensive for computer hardware, many systems use simpler versions that are "good enough."

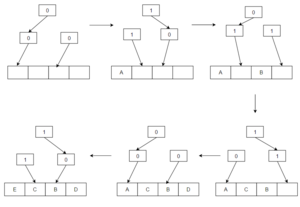

Pseudo-LRU (PLRU)

For very large caches, a perfect LRU system is too complex. PLRU is a simpler way that almost always removes one of the least recently used items. It uses less power and is faster than a full LRU system, even if it's not quite as perfect.

Imagine a set of arrows. When you use a piece of data, the arrows pointing to it flip to point somewhere else. When the cache is full, you follow the arrows to find the item to replace.

CLOCK-Pro

CLOCK-Pro is another simplified version of LRU, designed to be efficient for operating systems. It's like a clock hand moving around the cache. It keeps track of how often data is used and how recently. It's good at quickly removing data that's only used once. Many modern computer systems, like Linux, use a mix of LRU and CLOCK-Pro.

Simple Frequency-Based Policies

Least-Frequently Used (LFU)

This policy counts how many times each piece of data has been used. When the cache is full, it removes the data that has been used the fewest times. So, if you have a file that's been opened 100 times and another that's only been opened 5 times, the one opened 5 times will be removed first.

Least Frequent Recently Used (LFRU)

LFRU tries to combine the best parts of LFU (how often something is used) and LRU (how recently something is used). It divides the cache into two parts: a "privileged" part for very popular items and an "unprivileged" part. Popular items move to the privileged part, and less popular ones are removed from the unprivileged part.

LFU with Dynamic Aging (LFUDA)

LFUDA is a version of LFU that helps with a problem called "cache pollution." Sometimes, an item might have been very popular in the past, but now it's not used much. With regular LFU, it might stay in the cache forever because its "use count" is so high. LFUDA adds a "cache age" factor that helps reduce the count of old, unused items, making them eligible for removal.

Policies that Try to Predict the Future

Some advanced cache policies try to guess which data will be needed in the future, similar to Bélády's algorithm.

Hawkeye

Hawkeye tries to predict if data will be used again soon or not. It watches how your computer uses data and learns which instructions create "cache-friendly" data (data that will be used again) and "cache-averse" data (data that won't be used again). It then uses this prediction to decide which data to keep and which to remove. Hawkeye won a big competition for cache policies in 2017!

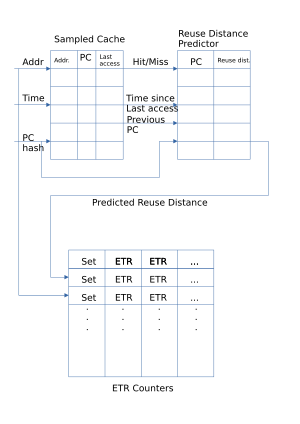

Mockingjay

Mockingjay is an even newer policy that tries to improve on Hawkeye. It makes more detailed predictions about when data will be reused. It keeps track of when data was last accessed and uses that to estimate when it might be needed again. When the cache is full, it removes the data that is predicted to be needed farthest in the future (or has been needed farthest in the past and wasn't used). Mockingjay gets very close to the perfect performance of Bélády's algorithm.

Cache Policies Using Machine Learning

Some researchers are exploring using machine learning (like how AI learns patterns) to predict which data to remove from the cache. This allows the cache to "learn" from past usage patterns to make better decisions.

Other Cache Replacement Policies

Adaptive Replacement Cache (ARC)

ARC constantly tries to find the best balance between LRU (least recently used) and LFU (least frequently used). It learns from how the cache is being used and adjusts itself to make the best use of the available space.

Clock with Adaptive Replacement (CAR)

CAR combines the good ideas from ARC and the CLOCK algorithm. It performs very well, often better than LRU and CLOCK alone. Like ARC, CAR automatically adjusts itself without needing special settings from the user.

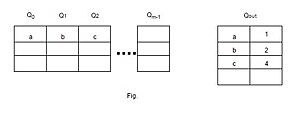

Multi Queue (MQ)

The Multi Queue algorithm uses several LRU queues (Q0, Q1, Q2, etc.) to manage data. Each queue holds data based on how long it's expected to stay in the cache. Data that's used more often gets promoted to a higher queue, meaning it stays in the cache longer. If data isn't used for a while, it gets demoted to a lower queue or removed.

For example, data accessed only once might go into Q0. Data accessed twice might go into Q1, and so on. When the cache is full, data from the lowest queue (Q0) is removed first.

Pannier: Container-based caching algorithm for compound objects

Pannier is a special caching method for flash storage (like in your phone or SSD drive). It groups data into "containers" and ranks these containers based on how long their data is expected to stay useful. It also helps manage how much data is written to the flash storage to make it last longer.

See also

In Spanish: Algoritmo de caché para niños

In Spanish: Algoritmo de caché para niños

- Cache-oblivious algorithm

- Locality of reference

- Distributed cache