Centriole facts for kids

A centriole is a tiny, tube-shaped part inside most eukaryotic cells. Think of it like a small, organized cylinder. It's mostly made of a protein called tubulin. Centrioles are super important for how cells work and divide. They help create structures like cilia and flagella, which are like tiny hairs or tails that help cells move or sense things. They also play a key role when a cell gets ready to split into two new cells. You won't find centrioles in all living things, though. For example, most flowering plants and fungi don't have them.

Contents

What are Centrioles?

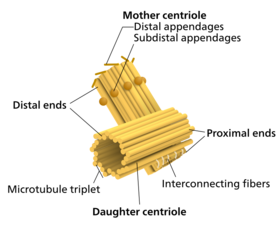

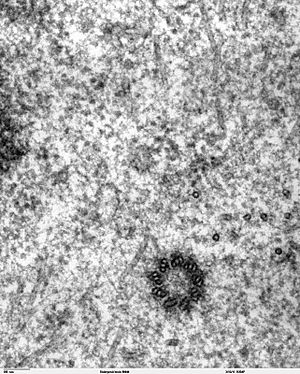

Centrioles are usually built from nine groups of short microtubules. These microtubules are arranged in a cylinder, almost like a tiny barrel. Each group typically has three microtubules, called a triplet. However, some creatures have slightly different setups. For instance, crabs and fruit fly embryos have nine pairs of microtubules instead of triplets. Other important proteins, like centrin, also help make up a centriole.

A pair of centrioles often works together. They are surrounded by a special material called the pericentriolar material (PCM). This whole structure, the two centrioles plus the PCM, is known as a centrosome. The centrosome acts like the main control center for organizing the cell's internal skeleton.

How Centrioles Help Cells Divide

Centrioles are very important during cell division. When a cell is getting ready to split, centrioles help form the mitotic spindle. This spindle is like a framework that pulls the cell's DNA apart evenly into the two new cells. They also help finish the process of cytokinesis, which is when the cell fully divides its cytoplasm.

Scientists once thought centrioles were absolutely necessary for the spindle to form in animal cells. But newer studies have shown that some cells can still divide even if their centrioles are removed. For example, certain fruit flies without centrioles can still grow normally. However, their adult cells might lack flagella and cilia, which are important for movement. This shows that while centrioles are usually there, cells can sometimes find other ways to manage.

Centrioles and Cell Structure

Centrioles are key parts of centrosomes. Centrosomes are like the main organizers for the cell's internal "roads" called microtubules. These microtubules help give the cell its shape and move things around inside. The location of the centrioles helps decide where the cell's nucleus will be. This is crucial for how the cell is shaped and how it works.

Centrioles in Reproduction and Development

Centrioles play a vital role in reproduction and the early growth of animals.

Making Cilia and Flagella

In cells that have flagella (like sperm tails) or cilia (tiny hair-like structures), the mother centriole becomes a basal body. This basal body acts as the anchor and starting point for building the flagellum or cilium. If cells can't use centrioles to make these structures correctly, it can lead to certain health problems. For example, issues with centrioles moving into the right place before building cilia have been linked to conditions like Meckel–Gruber syndrome.

Centrioles in Animal Growth

Centrioles are also important for how animals develop. For instance, in early mammal embryos, the correct placement of cilia by centrioles helps set up the body's left-right asymmetry. This means deciding which side will be the left and which will be the right, which is important for organ placement.

How Centrioles Make Copies

Before a cell divides, it needs to make copies of its centrioles. Each cell starts with two centrioles: an older one called the mother centriole and a younger one called the daughter centriole. When it's time to copy, a new centriole starts to grow next to both the mother and daughter centrioles.

These new centrioles are built at a specific end of the existing ones. After they are copied, the two pairs of centrioles stay connected until the cell is ready for mitosis. Then, a special enzyme helps them separate. Each new cell that forms after division will get one of these centriole pairs. This ensures that every new cell has the necessary structures to function properly.

Different Kinds of Centrioles

Most centrioles have a standard structure: nine groups of three microtubules arranged in a circle. But some centrioles are a bit different. For example, in fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster), centrioles have nine pairs of microtubules instead of triplets. In a tiny worm called Caenorhabditis elegans, they have nine single microtubules.

There are also "atypical" centrioles that might not have microtubules at all, or their microtubules aren't arranged in a perfect circle. An example is found in human sperm. These atypical centrioles can be very important for specific functions. For instance, the unusual distal centriole in sperm helps connect the sperm's tail movement to its head. This makes the sperm swim more effectively, which is important for reproduction. Scientists believe these special centrioles have evolved many times to help animals adapt.

The Story of Centriole Discovery

The idea of centrioles and centrosomes has been around for a long time. Scientists like Walther Flemming and Edouard Van Beneden first described the centrosome in the late 1800s. Theodor Boveri gave them the names "centrosome" in 1888 and "centriole" in 1895. Later, around the 1950s, Étienne de Harven and Joseph G. Gall figured out how centrioles make copies of themselves.

Where Centrioles Came From

The very first common ancestor of all eukaryotes (cells with a nucleus) likely had centrioles and cilia. Over time, some groups of eukaryotes, like land plants, lost centrioles in most of their cells. However, some still have them in their moving male reproductive cells. For example, conifers and flowering plants don't have centrioles at all because their reproductive cells don't need to swim. Genes important for centriole growth are only found in eukaryotes, showing their unique role in these complex cells.

What the Name "Centriole" Means

The word "centriole" means "little central part." This name makes sense because centrioles are often found near the center of a cell.

See also

In Spanish: Centriolo para niños

In Spanish: Centriolo para niños