Cicer facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Cicer |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| the cultivated annual chickpea Cicer arietinum | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae |

| Tribe: | Cicereae |

| Genus: | Cicer L. |

| Species | |

|

|

|

|

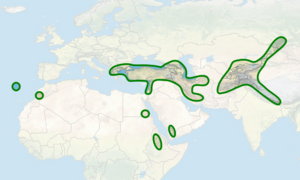

Cicer is a group of plants in the legume family, called Fabaceae. This family also includes peas, beans, and lentils. The Cicer group is the only one in its special tribe, Cicereae. These plants originally grew across the Middle East and Asia. The most famous and only plant from this group that people grow for food is Cicer arietinum, which you know as the chickpea!

Contents

Growing Cicer Plants

Right now, the only Cicer plant grown by farmers is C. arietinum, the chickpea. But scientists are looking at other types too.

The wild plant that chickpeas came from is called Cicer reticulatum. Since chickpeas grew from this wild plant, scientists think C. reticulatum might offer new kinds of edible chickpeas. Wild C. reticulatum pods often stay closed when they are ripe. This trait made them easier to turn into a farm crop. It means their features, like how they feel, their size, and their nutrients, could be changed over time.

Domesticated chickpeas can grow and flower at any time of the year. Wild C. reticulatum, however, needs a long period of cold weather before it can grow well. This means it can only grow in certain areas.

Even though C. reticulatum could become a new food source, it's hard to domesticate. One problem is that it doesn't have much genetic variety to improve chickpeas. Also, wild C. reticulatum grows in a small area. This makes it hard to collect and save its seeds for future use.

In the past, trying to breed new chickpeas has been tough because of a lack of genetic variety. This has made it hard to make chickpeas resistant to diseases like Ascochyta blight and Fusarium wilt. There have also been problems with insects breaking through chickpea pods. It's also been hard to make them tolerate dry weather or very hot temperatures.

To fix these issues, scientists need to add new genes from wild plants. This will make cultivated chickpeas more diverse. Currently, the closest wild relatives, C. reticulatum and Cicer echinospermum, are the main sources of new genes. Scientists are also looking at other, more distant Cicer species for useful genes.

Strong Cicer Plants and How They Can Be Improved

Some Cicer plants that live for many years (called perennials) are very tough. They can survive in harsh environments better than other plants. Even if some are hard to harvest, scientists are working to make them easier to grow. Studies show that certain perennial Cicer species have special strengths. For example, Cicer canariense, a perennial, can be made to grow better with scientific help.

Cicer canariense seeds often don't sprout well because they have very hard outer coats. But scientists have found ways to help them sprout. They can use strong chemicals like sulphuric acid or hot water. One study found that scratching the seed coat or soaking it in sulphur worked best. More research could make this plant a new food source.

Another perennial plant, Cicer anatolicum, is much better at resisting chickpea ascochyta blight than the chickpeas we eat. But it's hard to mix its genes with cultivated chickpeas. Studies show that if scientists can match the plant hormones between the two types, they might be able to create new hybrid plants. This could help make modern chickpeas stronger.

Many Cicer plants, both perennials and annuals (plants that live for one year), grow in different climates. So far, no perennial Cicer species has grown well in hot, wet places where annual Cicer species thrive. If scientists could save and transport the pollen of perennial species, they could try cross-breeding them in new places. This would help use the genes from perennial plants more effectively.

A big problem for Cicer plants is a pest called the bollworm, Helicoverpa armigera. Finding plants that can resist this pest is a good solution. A study found that perennials like C. canariense and C. microphyllum are very resistant to this worm. This is much better than C. judaicum, an annual plant. More studies on cross-breeding could show where this resistance comes from. Drought resistance is another challenge for many Cicer perennials.

About 90% of the world's chickpeas grow in areas with very little rain. Drought is a major problem for their growth. A study compared how well many perennials resisted drought compared to annuals. The perennial wild Cicer species recovered after wilting and drying out. They also handled high temperatures well. Among all the perennials tested, Cicer anatolicum should be studied for cross-breeding. This is because it is genetically similar to the annual chickpea.

These strengths in wild Cicer perennials could help scientists find genes that make plants tough. Resistance to drought and pests, along with better ways to grow crops, are important for the future of Cicer plants. More studies on mixing genes and cross-breeding between Cicer perennials could improve our food crops. It could also give us new ideas for plant innovation.

How Cicer Plants Changed Over Time

The Cicer group has many different kinds of plants. This makes them interesting for growing as food crops. Today, only one Cicer species, the modern chickpea, is grown by farmers. But scientists are looking at other types to grow, especially perennial crops. One exciting idea is to mix annual and perennial species. However, this mixing (called hybridization) only works between certain species, and scientists are still figuring out which ones.

To expand into perennial crops, the first step is to look at how perennial and annual Cicer species are related. Scientists study their physical traits and their genes. Unfortunately, research shows big differences between perennial and annual Cicer plants. This suggests that mixing them to create new types might be hard. For example, a study on seed coats showed clear differences between the two groups. Genetic studies also showed that annual species (called Monocicer) and perennial species are quite far apart in their family tree.

More research has looked at how closely related annual and perennial species are. Scientists studied 12 different gene locations. They found one perennial species, C. incisum, that was more closely related to annual plants than other perennials. This was also seen in genetic family trees. While most annual and perennial species form their own separate groups, C. incisum is an exception. Another exception is C. cuneatum, an annual species. It is more closely related to the perennial C. canariense than to other annuals. These exceptions suggest that there might be close relatives that could be grown as new crops. Even though there's a big evolutionary gap between modern perennial and annual species, this research gives hope for growing a perennial Cicer as a food crop.

Creating New Cicer Plants Through Hybridization

Hybridization is when two different species reproduce to create a unique new plant. This is very important for making new food crops from existing plants. Based on past genetic studies, creating a hybrid between perennial and annual Cicer species looks promising. Many steps have been taken to improve how scientists create these hybrids. But it has been hard to make a healthy new plant from these crosses. As expected, it's been easier to mix annuals with annuals, and perennials with perennials.

However, some research has shown success in crossing specific annual and perennial Cicer species. One successful cross was between the annual C. cuneatum and the perennial C. canariense. The new plant from this cross was partly able to reproduce and looked like a mix of both parents.

This success depends on which plant provides the egg and which provides the pollen. This can make growing the new crop harder. This cross is special because it's one of the few times annual and perennial crosses have partly worked. Also, the species crossed, C. cuneatum and C. canariense, were already known to be closely related from earlier studies on their evolution.

This kind of research is key to developing a perennial food crop related to the modern chickpea. Perennial crops are better for food production because they are more sustainable. They don't need to be replanted every year. As you can see, understanding how species are related genetically and through evolution is crucial for creating new hybrid plants.

See also

In Spanish: Cicer para niños

In Spanish: Cicer para niños