Cotehele clock facts for kids

The Cotehele clock is a very old and special clock found at Cotehele House in Calstock, Cornwall. It is the oldest turret clock (a large clock often found in a tower) in the United Kingdom that still works exactly as it was first built. It's also still in its original spot! This amazing clock was probably put in place between 1493 and 1521.

Contents

History of the Cotehele Clock

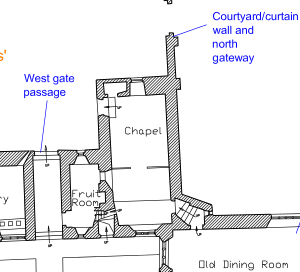

The first chapel at Cotehele House was built around 1411. Only parts of its original walls remain today.

Piers Edgcumbe became the owner of Cotehele House in 1489. He married Joan Durnford in 1493. She passed away in 1521. Because of special artworks made to celebrate their marriage, it's likely that the chapel was worked on starting in 1493. The clock's special spot (called an alcove) was added to the chapel's west wall during this time. Experts believe the clock was installed between 1493 and 1521, possibly closer to the earlier date.

This clock is known as the oldest turret clock in the UK that still works in its original form and place. It doesn't have a clock face. Instead, it's connected to a bell that rings to tell the hour.

Most old clocks like this were changed over time to use a pendulum. But the Cotehele clock was never changed. This makes it one of the oldest clocks that still uses its original "verge escapement" and "foliot" system. Other famous clocks, like the Salisbury Cathedral clock, were changed and then later put back to their original style.

The building dates for the Salisbury and Wells Cathedral clocks are debated. They are likely from the early 1500s. This means the Cotehele Clock might actually be the oldest working turret clock in the UK. Many turret clocks were built in the 1300s, but none of them survived. The special care at Cotehele House made sure this clock was never replaced or thrown away.

The alcove where the clock sits seems to have been built just for it. It has a special chute that goes up to the bell. The space is just right for the clock, its weights, and the pulley system. It's unlikely that an old, used clock would have been bought for such a grand new building. Also, the Cotehele clock looks very similar to clocks at Castle Combe and Marston Magna.

Clock Care and Upgrades

1962 Overhaul

In 1962, the clock was taken apart and sent to a company called Thwaites & Reed for repair. Some parts were worn but still okay, so they were left as they were. Other parts were repaired with new steel. After the work, the clock was put back together at Cotehele.

During this repair, a part called the "strike release mechanism" was replaced. The new part has the company's name and date stamped on it. The wooden frame holding the clock also seems to have been replaced.

2002 Overhaul

Another big project happened in 2002. The goal was to get the clock and bells working perfectly for the Queen’s Golden Jubilee celebration that June.

Peter Watkinson, an expert in old clocks, worked on it. He took the clock apart, cleaned everything carefully, added grease, and put it back together. If the weights are set correctly, the clock can keep time to within a few minutes each day. The sound of the bell ringing the hour adds a lot to the feeling of Cotehele, just as it has for 500 years.

The clock uses two weights. One weight powers the part that tells the time. The other weight powers the part that makes the bell strike. Today, the clock is started in the morning and stopped in the afternoon. But it could run for a full 24 hours if it were fully wound.

How the Cotehele Clock Works

The part that makes the bell strike is at the top of the clock. The part that tells the time is below it.

Clock Frame

The clock's frame is made from strong wrought iron. It has two tall posts and horizontal bars at the top and bottom. These bars are strongly fixed together. The whole frame is about 115 centimeters (about 45 inches) tall. The iron bars are about 4 centimeters (1.5 inches) wide.

Going Train (Time-Telling Part)

The "going train" is the part of the clock that keeps track of time. It has several gears. The largest gear, called the great wheel, turns once every hour. The "foliot" is a horizontal bar that swings back and forth. It helps the clock tick.

The foliot is about 89 centimeters (35 inches) wide. It has small grooves on each side where tiny weights can be moved. Moving these weights helps adjust how fast the clock runs. The "verge" is a vertical rod connected to the foliot. It has two small paddles, called pallets, that interact with the escapement wheel.

The going train is wound using a special handle with four spokes. The rope can be wound around the barrel many times. This means the clock could run for a full day and night without needing to be wound again.

It's interesting that the great wheel has 95 teeth instead of 96. If it had 96 teeth, the timing would be much simpler. This suggests the clock was made in the late 1400s. At that time, clockmakers mostly cared about hours, not minutes or seconds.

Also, the small section on the foliot for adjusting weights shows this clock was always meant to measure "equal hours." This means every hour was the same length, unlike some older clocks that had "unequal hours" (where hours were shorter in winter and longer in summer).

Striking Train (Bell-Ringing Part)

The "striking train" is the part of the clock that makes the bell ring. The great wheel of this train has 78 teeth and 8 pins. These pins push a lever that makes the bell strike.

This part of the clock also has a "count wheel." This wheel turns once every 12 hours. It has 78 teeth on the outside and 12 notches on the inside. These notches help the clock strike the correct number of times for each hour (1 for 1 o'clock, 2 for 2 o'clock, and so on, up to 12). If you add up all the strikes from 1 to 12, it equals 78 strikes in 12 hours.

The barrel of the striking train can hold enough rope to make the clock strike 156 times. This is enough for a full 24 hours of ringing.

Clock Weights

The going train (time-telling part) uses a stone weight. The striking train (bell-ringing part) uses an iron weight. The iron weight is about 40 kilograms (about 88 pounds). The stone weight is a little heavier. Both weights use a special double-pulley system. This means they only drop half the distance of the rope, and they put half their actual weight's force on the clock.

How Accurate is the Cotehele Clock?

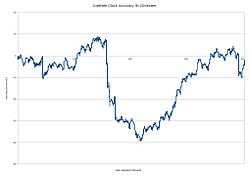

Experts measured the clock's accuracy on May 5, 2011, for over three hours. The clock's time varied, sometimes being 10 seconds fast and sometimes 40 seconds slow. It's hard to guess how accurate it will be from day to day.

There are a few reasons why the Cotehele Clock's accuracy changes:

- The part that holds the verge (the vertical rod) is not original and causes some rubbing. If it were suspended by a string, it would work more smoothly.

- The foliot (the horizontal bar) swings at a slight angle, not perfectly flat.

- The escapement wheel and the verge's paddles don't always connect perfectly. This can cause the paddles to "fall" onto the teeth, making the clock vibrate. This might be due to wear over many years or how the paddles were rebuilt during an earlier repair.

- The part that releases the strike mechanism is heavier than the original. This extra weight can put more pressure on the time-telling part of the clock just before it strikes.

Even with these small changes, the Cotehele clock was a great way to tell time in the 1400s and 1500s. Back then, sundials could be off by as much as 15 minutes throughout the year. If the Cotehele clock ran 24 hours a day (the bell could be turned off at night), it only needed to be adjusted every few days. This could be done at noon using a sundial when the sun was out. Even if the sun wasn't visible for a long time, the clock would still keep good enough time if it was wound fully once a day.

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |