Crash at Crush facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

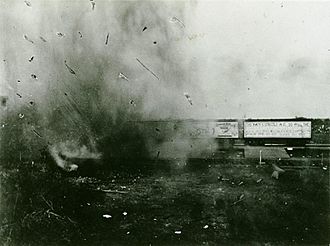

The locomotive boilers explode during impact

|

|

| Date | September 15, 1896 |

|---|---|

| Location | "Crush", McLennan County, Texas, United States |

| Type | Train wreck publicity stunt |

| Organized by | Missouri–Kansas–Texas Railroad |

| Deaths | 2 |

| Non-fatal injuries | 6+ |

The Crash at Crush was an amazing, but also sad, event that happened in Texas on September 15, 1896. It was a special show where two empty locomotives (train engines) were crashed into each other at high speed. This was planned as a way to get people excited about the Missouri–Kansas–Texas Railroad, also known as the "Katy" Railroad.

William George Crush, who worked for the Katy Railroad, came up with this big idea. He wanted to create a huge public show. There was no charge to watch the crash. However, people paid a special low price of US$3.50 (equivalent to $123.12 in 2022) to ride the train to the crash site. This temporary town was even named "Crush" just for the event!

About 40,000 people came to watch, which was a huge crowd for that time. But something unexpected and terrible happened. When the trains crashed, their large steam boilers exploded. This sent pieces of metal and wood flying everywhere. Sadly, two people died, and many others were hurt.

Contents

How Was the Crash at Crush Planned?

The Katy Railroad had built tracks through the Crush area in the 1880s. As the railroad grew, they got newer, more powerful engines. This meant they had many older, smaller steam engines they no longer needed.

In 1896, William Crush suggested using these old trains for a big show. He chose a spot about 14 miles (23 km) north of Waco. A similar train crash show had been very popular in Ohio earlier that year. Crush thought the Katy Railroad could do something similar and attract thousands of passengers.

His bosses at the railroad agreed to the plan. They put him in charge of everything. The railroad decided not to charge for the show itself. Instead, they would make money by selling tickets for special trains to the site. A round-trip ticket from anywhere in Texas cost US$3.50 (equivalent to $123.12 in 2022).

Setting Up the Temporary Town of Crush

To prepare for the big day, two water wells were dug. A large circus tent from Ringling Brothers was set up. There were also places for people to sit, stands for speakers, and a special area for reporters. Two telegraph offices were built, along with a train station. A giant sign above the station proudly announced the new town: "Crush, Texas."

The event also had many fun activities, like those found at a carnival. There were lemonade stands, games, and other side shows. People were very excited about these extra attractions.

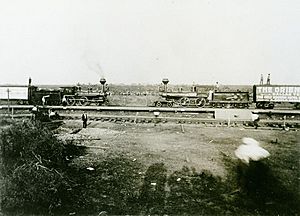

A special four-mile section of track was built just for the crash. This track was separate from the main railroad line. This made sure that a runaway train could not accidentally get onto the main tracks. Each end of this special track was on a small hill. The trains would meet in the valley between these hills. The two engines used were old Baldwin engines, No. 999 and No. 1001.

Safety Measures for the Spectators

The day before the crash, railroad officials tested the engines' speed. This helped them guess where the trains would crash. Katy engineers told Crush that the event would be safe. They believed the engines' boilers were strong and would not explode, even in a high-speed crash.

Each engine would pull six boxcars. The cars were chained together tightly. This was to prevent them from breaking apart during the impact.

Crush insisted that the public stay at least 200 yards (180 m) away from the track. However, members of the press were allowed to be closer, at 100 yards. Railroad officials expected about 20,000 to 25,000 people. But the clever advertising worked even better than planned! The railroad sold out more than 30 special trains for the event.

The Big Crash

The crash was delayed for an hour. This was because the huge crowd did not want to move back to the safe distance. Around 5:00 PM, the two trains, carrying railroad ties, slowly met in the middle of the track. They stopped for photographs. Then, they rolled back to their starting points at opposite ends of the track.

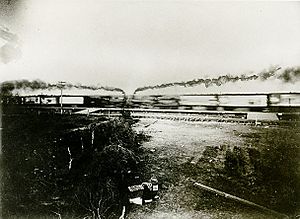

Crush, riding a white horse, signaled the start of the main event. The engineers and crew on each train set the steam to a certain level. They rode for exactly four turns of the driving wheels, then jumped off the trains.

The Dallas Morning News newspaper described the exciting moment:

The rumble of the two trains, faint and far off at first, but growing nearer and more distinct with each fleeting second, was like the gathering force of a cyclone. Nearer and nearer they came, the whistles of each blowing repeatedly and the torpedoes which had been placed on the track exploding in almost a continuous round like the rattle of musketry...

They rolled down at a frightful rate of speed to within a quarter of a mile of each other. Nearer and nearer as they approached the fatal meeting place the rumbling increased, the roaring grew louder...

Each train reached a speed of about 45 miles per hour (72 km/h) when they crashed. Some people thought they were going even faster.

Right after the trains hit, there was a huge explosion:

A crash, a sound of timbers rent and torn, and then a shower of splinters... There was just a swift instance of silence, and then as if controlled by a single impulse both boilers exploded simultaneously and the air was filled with flying missiles of iron and steel varying in size from a postage stamp to half of a driving wheel...

Pieces of the trains flew hundreds of feet into the air. People in the crowd panicked and ran. Some of the flying debris hit spectators. Sadly, two people were killed, and at least six others were badly hurt. A photographer named Jarvis "Joe" Deane lost one eye from a flying bolt. The trains and their boxcars were completely destroyed. They became just piles of broken metal and wood.

What Happened After the Crash?

The story of the Crash at Crush was in newspapers all over the country. William Crush was immediately fired from the Katy Railroad. But because the event brought so much attention, he was hired back the very next day! He continued to work for the company for six decades until he retired.

The Katy Railroad quickly paid money to the families of the victims. They also gave lifetime train passes to some. The injured photographer received US$10,000 (equivalent to $351,760 in 2022) for his injuries. Even though the event ended in tragedy, the Katy Railroad became very famous because of it. Many other railroads continued to stage train crashes in the years that followed.

A famous ragtime composer named Scott Joplin was performing in the area at the time. He wrote a piano song called the "Great Crush Collision March" to remember the crash. This song was special because it included instructions on how to make sounds like the trains crashing.

In 1976, the Texas Historical Commission placed a historical marker near the site in West, Texas.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |