Disappearing gun facts for kids

A disappearing gun was a special type of gun that could hide itself after firing. It was mounted on a disappearing carriage. This design allowed the gun to stay safe from enemy fire and observation.

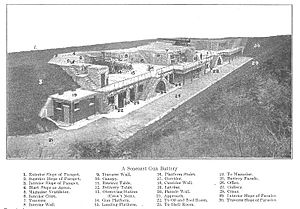

Most of these carriages let the gun move backward and down. It would go behind a protective wall or into a hidden pit after shooting. A few designs simply used a platform that could be pulled back. Either way, pulling the gun back hid it from view. This also protected it from direct enemy fire while it was being reloaded.

Reloading became easier too. The gun's back part (the breech) would lower to a good height. This meant shells could be rolled right up to the open breech for loading. Disappearing guns also fired faster and made the gun crew less tired.

However, some disappearing carriages were very complex. It was also hard to protect them from air attacks. Most of them could not aim very high. Because of these issues, building new disappearing gun setups mostly stopped by 1918. The very last one was a large 16-inch gun at Fort Michie in New York, finished in 1923. In the U.S., these guns were still common for coast defense until World War II. This was because there wasn't enough money for newer weapons.

Even though some early designs were for field use, disappearing guns became known for fixed forts. Most of these were coastal artillery, meaning they defended coastlines. One rare exception was in Switzerland's mountain forts. Six 120mm guns on special rail-mounted carriages stayed at Fort de Dailly until 1940.

The gun usually moved down using the force of its own recoil (the kickback from firing). But some also used compressed air. A few were even built to be raised by steam power.

Contents

How Disappearing Guns Were Invented

Captain (later Colonel Sir) Alexander Moncrieff made big improvements to gun carriages. He wanted a gun that could rise above a wall to fire, then reload safely behind cover. He got his ideas from watching the Crimean War. His design was the first to be widely used, especially in British Empire forts.

Moncrieff's main new idea was a clever counterweight system. This system not only raised the gun but also controlled its powerful recoil. He said his system was cheaper and faster to build than older gun setups.

People had thought about such a system before. Some early ideas involved platforms that could be raised or special wheels with built-in weights. Some even used two guns where one acted as a counterweight for the other.

An early attempt in the U.S. was King's Depression Carriage in the 1860s. It used a counterweight to move a large 15-inch gun up and down a ramp. This let the gun reload and aim from behind cover. But it still needed a lot of manual work and was not widely used.

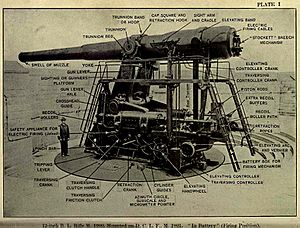

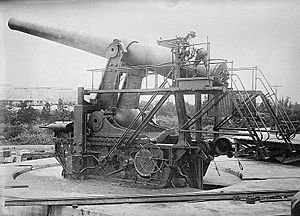

Later, in the 1880s, Adelbert Buffington and William Crozier made the design even better. Their Buffington–Crozier Disappearing Carriage (1893) was the best of its kind. Very large guns, up to 16 inches, were put on these carriages.

Disappearing guns became very popular in the British Empire, the United States, and other countries. In the U.S., they were the main weapons in forts built between 1898 and 1917.

Around 1893, France and Germany also developed mobile disappearing guns. These could move on roads or rails. France used them for 120mm and 155mm guns in World War I. Switzerland also used 120mm guns on these mounts at Fort de Dailly.

Even though they were good against ships, these guns were easy targets for airplanes. After World War I, coastal guns were usually put inside strong concrete rooms (casemates) or hidden with camouflage. By 1912, the British Army considered disappearing guns old-fashioned. Only a few countries, like the U.S., kept building them until World War I. They stayed in service until newer weapons replaced them in World War II.

The only major battle where U.S. disappearing guns were used was during the Japanese invasion of the Philippines in World War II. These guns were meant to stop warships from entering Manila Bay. But they couldn't turn enough to fight the Japanese ground forces. Even with camouflage, their positions were easy targets for air attacks and high-angle artillery.

What Was Good About Disappearing Guns?

Disappearing carriages had several main benefits:

- Protection for the crew: The gun crew was safe from direct enemy fire. The gun only popped up to shoot, then went back down.

- Hard to spot: When the guns were hidden, the fort was much harder for enemy ships to see. Flat-shooting cannon fire would often fly right over the battery without hitting it.

- Less strain on the fort: The way the gun moved reduced the stress on its platform. This meant the fort could be built with lighter materials.

- Cheaper to build: Simple gun pits made of earth and stone were much cheaper than building big, strong walls and protected rooms for guns.

- Surprise attacks: The whole battery could be hidden when not in use. This allowed for surprise attacks.

- Faster firing: They could fire more rounds per minute than guns that stayed in the open.

- Less tiring for crew: The crew didn't get as tired because reloading was easier.

What Were the Problems?

Disappearing guns also had some downsides:

- Limited aiming height: Some British designs couldn't aim very high (under 20 degrees). This meant they couldn't shoot as far as newer naval guns. (Later U.S. designs could aim up to 30 degrees).

- Slower firing rate: The time it took for the gun to swing up, fire, swing down, and reload could slow down the rate of fire. Some British guns fired only one shot every one to two minutes.

- Hard to aim quickly: As warships got faster, guns needed to fire more quickly. A disappearing gun couldn't be aimed or moved while it was in the lowered position. The gunner had to climb up to aim after it came back up.

- Expensive and complex: They were more complex and costly than simpler gun mounts. In 1918, a 12-inch disappearing gun cost $102,000, while a simpler mount cost $92,000. However, the cheaper cost of building the fort around them sometimes made up for this.

Other Uses of the Idea

Gun Lift Battery

One very rare and complex type was Battery Potter at Fort Hancock in New Jersey. This battery was built in 1892. Instead of using recoil to lower the gun, two 12-inch guns were placed on huge hydraulic elevators. These elevators would lift the 110-ton gun and carriage 14 feet (about 4 meters) to fire over a wall. After firing, the gun was lowered for reloading using hydraulic rams.

Battery Potter was slow, taking 3 minutes per shot. But its design allowed it to shoot in any direction (360°). This design was not used again, and Battery Potter was taken apart in 1907. It needed a lot of machinery, like boilers and steam-powered pumps. Its boilers had to run all the time, which was very expensive.

People also tried to use the disappearing gun idea on ships. HMS Temeraire, built in 1877, had two disappearing guns. These 11-inch guns would sink down into protective circular walls (barbettes) after firing. This was meant to combine the ability to turn with the protection of fixed naval guns.

This complex system seemed too difficult for the rough conditions at sea. The saltwater and constant rocking of the ship caused problems. However, a simpler version was used on river and harbor gunboats. The 1867 HMS Staunch had a large 9-inch gun on a lowering platform. This was a big success. These boats had a single large gun hidden behind hinged shields. The gun was not usually lowered between shots.

Similar Systems

U.S. "balanced pillar" and "masking parapet" mounts were a mix of simple and disappearing mounts. The guns were hidden when not in use. But once they started firing, they were out in the open. These mounts only allowed the gun to be pulled back at a certain angle. This meant you couldn't aim the gun while it was hidden.

In 1893, Germany developed an armored turret called a "Fahrpanzer" (mobile armor). It had a 53mm gun and could move on roads or rails. These were sold to other countries and used in World War I. They were often hidden in trenches or bunkers when not firing.

Retractable turrets were also similar. But they usually didn't use recoil to hide. Like the balanced pillar systems, they often stayed visible when firing. However, they could usually be aimed from cover, allowing for a surprise first shot. These were used a lot in European land defenses.

See also

- List of disappearing gun installations

- Coastal artillery

- Seacoast defense in the United States