Ebola virus cases in the United States facts for kids

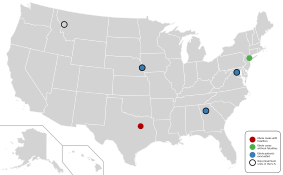

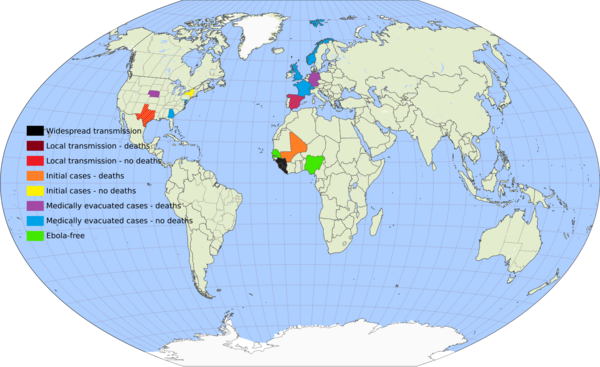

In 2014, the United States saw a few cases of Ebola virus disease, often just called "Ebola." This happened during a large Ebola outbreak in West Africa. In total, 11 people in the U.S. were diagnosed with Ebola.

Seven of these people were Americans who got sick with Ebola in other countries and were flown back to the U.S. for special medical care. Two of these seven people sadly passed away. The first case diagnosed in the U.S. was in September 2014.

Two people actually caught Ebola while they were in the United States. Both were nurses who cared for an Ebola patient. Luckily, both of these nurses recovered fully. After November 2014, no new cases of Ebola were found in the U.S.

Ebola Cases Diagnosed in the U.S.

First Case: Thomas Eric Duncan

Thomas Eric Duncan's Journey from Liberia

Thomas Eric Duncan was from Monrovia, Liberia. This country was hit very hard by the Ebola outbreak. On September 15, 2014, Duncan helped a sick pregnant woman get to an Ebola treatment center. She later died from Ebola.

On September 19, Duncan flew from Liberia to Brussels, then to Washington D.C., and finally to Dallas, Texas. He arrived in Dallas on September 20, 2014, and stayed with his family.

Duncan's Illness in Dallas

Duncan started feeling sick on September 24, 2014. He went to the Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital emergency room on September 25. He had a fever and other symptoms. The hospital staff didn't ask about his recent travel to Liberia at first. He was sent home with medicine that doesn't work for viruses.

His condition got worse, and he returned to the same hospital on September 28. This time, doctors learned he had come from Liberia and immediately suspected Ebola. They began following strict safety rules. On September 30, tests confirmed he had Ebola.

Duncan was very sick and his organs began to fail. Nurses Nina Pham and Amber Joy Vinson cared for him constantly. He was given an experimental medicine. Sadly, Thomas Eric Duncan died on October 8, 2014. He was the first person to die from Ebola in the U.S.

Finding People Who Had Contact with Duncan

After Duncan was diagnosed, health officials worked to find everyone he might have had contact with. This process is called "contact tracing." They monitored about 50 people who had low risk of exposure and 10 people who had high risk, like his close family and ambulance workers.

Everyone was watched daily for symptoms. By November 7, 2014, Dallas was officially declared "Ebola free." This meant that 177 people who were monitored had passed the 21-day period without getting sick.

Reactions to Duncan's Case

The Liberian government said they might prosecute Duncan if he returned. This was because he had filled out a form saying he had not been in contact with an Ebola case, which was not true.

Duncan's family felt he didn't get good care at the hospital. The hospital stated they gave him the best care possible. The hospital also saw fewer patients coming in after the incident.

The situation with Duncan and the nurses who later got sick made many hospitals wonder if they were ready to treat Ebola patients safely.

Second Case: Nina Pham

On October 10, Nina Pham, a 26-year-old nurse who had cared for Thomas Eric Duncan, developed a fever. She was immediately isolated. On October 11, she tested positive for Ebola, becoming the first person to catch the virus in the U.S.

Hospital officials said Pham had worn the recommended protective gear. On October 16, she was moved to a special hospital unit in Maryland. By October 24, she was declared free of the Ebola virus and even met President Obama at the White House.

Concerns About Hospital Safety

Initially, the head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Tom Frieden, suggested that a mistake in safety rules caused the infection. However, nurses' groups said the hospital didn't have clear rules or enough training for Ebola patients.

Nurses said they didn't get proper training or protective equipment. The CDC later admitted they could have been more active in managing the virus at the hospital. Nina Pham later sued the hospital's parent company, saying she got sick because of their lack of proper training and safety.

Third Case: Amber Vinson

On October 14, Amber Vinson, another nurse who had treated Duncan at the same hospital, reported a fever. She was quickly isolated. The next day, she tested positive for Ebola.

Before she felt sick, Vinson had flown on a commercial plane from Cleveland to Dallas. She had a slightly elevated temperature before boarding. The CDC had actually given her permission to fly because her temperature was not considered a "high risk" fever at the time.

As a precaution, people on her flights were asked to contact the CDC. Sixteen people in Ohio who had contact with Vinson were also monitored. On October 15, Vinson was moved to Emory University Hospital in Atlanta. Seven days later, she was declared Ebola-free.

Fourth Case: Craig Spencer

On October 23, Craig Spencer, a doctor who had treated Ebola patients in West Africa, tested positive for Ebola in New York City. He had just returned from working with Doctors Without Borders in Guinea.

Before he felt sick, Dr. Spencer had used public transport, walked in a park, and gone bowling. Health officials quickly worked to find anyone he might have been in contact with. They cleaned his apartment and the bowling alley. Officials said it was unlikely he could have spread the disease through public surfaces.

New York hospitals had prepared for Ebola patients. Dr. Spencer was treated in a special isolation unit at Bellevue Hospital. His condition improved, and on November 7, he was declared free of Ebola. He was released from the hospital on November 11, cheered by medical staff and hugged by the Mayor of New York, who declared the city "Ebola free."

This case led to discussions about funding for cities treating Ebola patients, as Dr. Spencer's care involved many healthcare workers and public health staff.

Americans Evacuated from West Africa

By the time the Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa ended in 2016, seven Americans had been flown back to the U.S. for treatment after catching Ebola while helping in West Africa.

- Kent Brantly and Nancy Writebol: These two aid workers got sick in Liberia in July 2014. They were flown to Emory University Hospital in Atlanta. Both recovered and were discharged on August 21. Brantly later donated blood to help other Ebola patients.

- Rick Sacra: A doctor from Massachusetts, Rick Sacra, was airlifted from Liberia in September 2014 to be treated in Omaha, Nebraska. He likely caught Ebola while performing surgery. He received a blood transfusion from Kent Brantly and was declared Ebola-free on September 25.

- Ian Crozier: In September 2014, another American doctor, later identified as Ian Crozier, was brought to Emory University Hospital. He was considered the sickest patient treated there but recovered.

- Ashoka Mukpo: An NBC News photojournalist, Ashoka Mukpo, tested positive for Ebola in Liberia in October 2014. He was evacuated to the University of Nebraska Medical Center. On October 21, he was declared Ebola-free and went home.

- Martin Salia: A doctor from Sierra Leone, who was a permanent resident of the U.S., became sick in November 2014. He was flown to the Nebraska Medical Center. He was very ill when he arrived, and sadly, he died from the disease on November 17.

- Preston Gorman: In March 2015, a U.S. physician assistant named Preston Gorman contracted Ebola in Sierra Leone. He was evacuated to the National Institutes of Health in Maryland. He was very sick but recovered and was discharged on April 9, 2015.

Efforts to Stop the Spread

Operation United Assistance

The U.S. military sent thousands of troops to West Africa as part of "Operation United Assistance." Their job was to build hospitals and treatment centers to help fight the Ebola outbreak there. This included a 25-bed hospital just for healthcare workers and 17 treatment centers, each with 100 beds, in Liberia.

Some U.S. soldiers returning from this operation were quarantined for 21 days as a safety measure.

Updated CDC Guidelines

The CDC provides rules for hospitals to control infections. Before October 2014, their guidelines for Ebola allowed hospitals some freedom in choosing protective gear.

However, after the nurses in Dallas got sick, many experts said the guidelines were not strict enough. On October 14, the U.S. officials changed their guidelines. This showed that there were problems with how healthcare workers were being protected.

The new guidelines, updated on October 20, gave very detailed instructions for personal protective equipment. They said no skin should be exposed and gave clear steps for putting on and taking off the gear. The CDC also clarified that Ebola could spread through wet droplets, like from sneezes.

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |