Fort Howell facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Fort Howell

|

|

| Nearest city | Hilton Head, South Carolina |

|---|---|

| NRHP reference No. | 11000371 |

| Added to NRHP | June 15, 2011 |

Fort Howell is an earthworks fort built in 1864 during the American Civil War. It's located on Hilton Head Island, South Carolina. The fort was named after Union Army Brigadier General Joshua B. Howell. Its main job was to protect Mitchelville, a special town for formerly enslaved people, which was located to its east.

Fort Howell was added to the National Register of Historic Places on June 15, 2011. It's also recognized as a site on the National Park Service's Network to Freedom, which is part of the Underground Railroad story. You can also find it on the Civil War Discovery Trail here. The Hilton Head Island Land Trust, Inc. owns the Fort. This group works hard to protect and keep the Fort safe forever.

Visiting Fort Howell Today

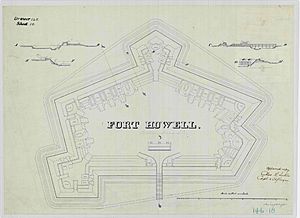

Fort Howell is a historic site you can visit! It's shaped like a five-sided enclosure, made from built-up earth. Even after almost 150 years, with trees and plants growing, you can still clearly see its shape.

Today, the Fort is open to everyone. There are places to park nearby and several signs that explain its history. You'll find a special kiosk with information about the Fort's past. Local artist Mary Ann Ford created cool metal figures of soldiers and other people, which are placed around the grounds.

It's free to visit Fort Howell, and it's open from sunrise to sunset. You can also take guided tours. These tours are offered by the Hilton Head Island Land Trust, Inc. and the Coastal Discovery Museum.

Fort Howell's History

Fort Howell is an earthworks fort built in 1864 during the American Civil War. It was constructed by soldiers from the 32nd United States Colored Infantry Regiment from Pennsylvania and the 144th New York Infantry. These regiments were part of the Union Army's forces on Hilton Head Island.

The Fort was built between late August and mid-October 1864. Soldiers used tools like shovels, spades, picks, and axes. They worked under the guidance of Captain Patrick McGuire and other engineers. Fort Howell was designed to be a strong, semi-permanent fort. It was meant to hold artillery guns and protect the nearby town of Mitchelville. This town was a new home for formerly enslaved people. The Fort was built on an open area, possibly a recently cleared forest or a cotton field.

The Fort was planned to hold as many as 27 guns. Some guns would fire over the top of the wall from wooden platforms. Others would fire through special openings in the wall. The Fort covers more than 3 acres of land.

Even though Fort Howell never saw any battles, it showed how skilled the engineers and soldiers were. It was a strong and well-built earthwork fort. Outside the fort, there was a moat (a ditch filled with water) and a wooden fence made of sharpened logs. These features were designed to slow down any attacking troops. Guns placed in special parts of the fort, called bastions, also protected the areas right next to the walls.

Building the Fort

Two Union Army regiments worked together to build Fort Howell. One was an African-American regiment, the 32nd United States Colored Infantry. The other was a white regiment, the 144th New York Infantry. This fort was an important addition to the defenses of Hilton Head Island late in the war.

In August 1864, orders were given to start building the fort near Mitchelville. The 32nd United States Colored Infantry was specifically assigned to this construction. They were told to provide as many soldiers as possible each day to work on the fort.

The soldiers from the 32nd United States Colored Infantry did most of the building. They worked from late August to mid-October 1864. They used shovels, picks, and axes under the supervision of Captain Patrick McGuire and other engineers. The 32nd United States Colored Infantry had about 500 officers and men. Like other black regiments during the Civil War, they had white officers and black non-commissioned officers and enlisted men.

Sometimes, the work was slow. It was common for Union commanders to assign black units to hard labor, like building forts. This allowed them to save white units for fighting. However, African-American soldiers and their white officers sometimes protested this treatment. They felt it was unfair to be given these tasks more often than white units, especially since it reminded them of enslaved people being forced to build forts for the Confederates.

For example, Private Nimrod Rowley, an African-American soldier, wrote to President Abraham Lincoln in August 1864. He complained that his regiment was given "the Spad and the Whelbarrow and the Axe" instead of muskets.

Engineers supervising the work at Fort Howell often wanted more soldiers assigned to construction. They expected 250 to 300 men daily, but often only 150 to 200 showed up for work on the fort. Many others were assigned to guard duty.

By mid-October, the 32nd United States Colored Infantry was moved to different locations. The 144th New York Infantry then took over and finished building the fort. They worked from mid-October to late November 1864, also supervised by engineers.

Fort Howell was completed near the end of 1864. By this time, the Confederate forces in the area were not strong enough to seriously threaten Hilton Head Island. So, Fort Howell never saw any battles.

Fort Engineering

Fort Howell is one of the best-preserved Civil War forts made of earth in South Carolina. It's special because it's a great example of a complex fort built by the Union Army. Most other surviving earthworks in South Carolina were built by the Confederate Army.

This fort shows how skilled United States Army engineers were. It was designed to be a strong defensive position. The way it was built, using packed earth reinforced with wood, was typical for forts of that time. However, its design was more detailed because it was meant for artillery guns, which stayed in fixed positions. Even though engineers designed it, infantry soldiers built it under their guidance.

Fort Howell has a five-sided shape with two bastions (outward-projecting parts) and a priest-cap (another type of projection). It also has four magazines (places to store ammunition) and spots for up to 27 guns. Sixteen of these were large "seacoast" or siege guns, and the other eleven were smaller field guns.

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |