Fortifications of Kingston upon Hull facts for kids

The city of Kingston upon Hull once had strong defenses to protect it. These included three main types of structures:

- The Hull town walls: These were made of brick and built in the early 1300s. They had four main gates, smaller back entrances called posterns, and many towers.

- Hull Castle: Built in the mid-1500s by Henry VIII, this castle was on the east side of the River Hull. It protected Hull's busy river harbor and had two strong blockhouses connected by a wall.

- The Citadel: This was a new, triangle-shaped fort built in the late 1600s. It replaced the old castle on the east bank of the river.

Over time, these defenses were removed. The town walls were taken down from the 1770s to make way for new docks. The Citadel was also demolished in the 1860s, and its land was used for shipbuilding and more docks.

Contents

Hull's City Walls

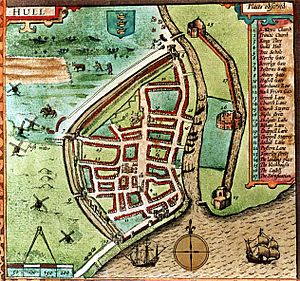

In the 1300s, Hull began building strong walls to protect itself. In 1322, King Edward I of England allowed the town to collect money for building walls. By 1327, they could build fortified walls and houses. The walls were mostly made of brick and were likely finished around 1356.

The walls stretched from the west side of the River Hull to the River Humber. They had gates at each end: Northgates near the River Hull and Hesslegates near the Humber. There were also gates in the middle called Beverley Gate and Myton Gate. A wall also ran along the Humber, with a gate called Water Gate for access to the river.

The town also had several smaller openings called posterns in the walls. These were only wide enough for one person and had a tower above them. In the 1500s, it was said there were more than twenty towers along the walls. After King Henry VIII visited in 1541, most entrances except the main gates were closed off.

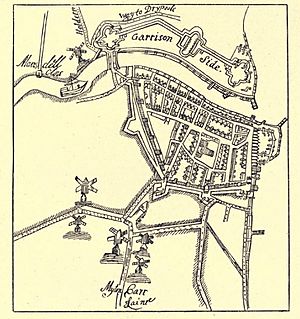

During the English Civil War (1642-1651), more defenses were added. Large earthworks, like half-moon shaped batteries for cannons, were built outside the main gates. A wide ditch was also dug outside the walls. The earth banks behind the walls were made taller. In 1646, a part of the wall near Myton Gate fell down, possibly because of heavy rain and the weight of the earth and cannons.

The walls were kept up in the late 1600s and 1700s. However, by 1752, they were in very poor condition.

Protecting the River Hull

The entrance to Hull by the River Hull was protected by a large chain stretched across the river's mouth. A tower on the east bank of the river, built around 1380, helped manage this chain. In the 1460s, a new chain and a winding machine (windlass) were installed to stop enemy ships from entering. In the 1590s, during fears of invasion, logs were added to the chain to help it float when deployed.

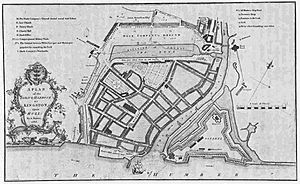

Walls Become Docks (1774–1829)

In 1774, the Hull Dock Company was created to build new docks for the town. This company took over the city walls and ditches west of the river. The walls were then torn down to make way for these new docks.

The first dock, later called Queen's Dock, was built in 1778 where Beverley and North gates once stood. A second dock, Humber Dock, opened in 1809 between Hessle and Myton gates. A third dock, Junction Dock (later Prince's Dock), opened in 1829 between the first two.

The southern walls along the Humber were removed in the early 1800s. By 1813, the land along the Humber had been extended outwards using earth dug up during the dock construction.

Hull Castle

After a rebellion called the Pilgrimage of Grace in 1536, King Henry VIII visited Hull in 1541. He ordered that the town's defenses be improved. He wanted the de la Pole house, which he now owned, to become the town's main fortress. He also wanted changes to the drainage system so the fields outside the town could be flooded if there was a threat.

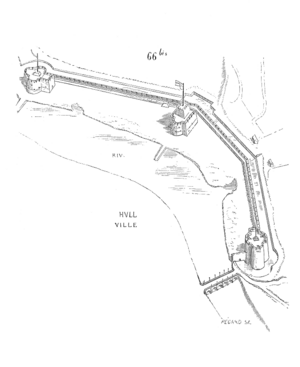

In 1542, Henry's plans grew to include building a new fortress. Hull Castle was finished by the end of 1543. It was built on the east bank of the River Hull. It had a main fort, "Hull Castle," and two smaller blockhouses at each end of a connecting wall. This wall stretched from the River Hull to the River Humber. At the same time, the first bridge across the River Hull, "North Bridge," was built just outside the town walls.

The main castle building was three stories tall with very thick walls. The blockhouses were smaller, two-story buildings. In 1552, the town of Hull took control of the Castle and blockhouses.

During the second Siege of Hull in 1643, the north blockhouse was partly destroyed when its gunpowder accidentally exploded. Both the blockhouse and North Bridge were later repaired.

By the 1680s, the castle needed major repairs. A Swedish engineer named Martin Beckman was put in charge of transforming the defenses on the east bank of the Hull. This work turned the old castle into a modern, triangular fort with a governor's house, a gunpowder storage building (magazine), and three barracks. This new fort became known as the Hull Citadel. The southern blockhouse and the main castle were included in the new Citadel. The northern blockhouse was outside the new fort and was later torn down in 1802.

The Citadel

The Citadel was a large, new fort built in the 1680s. It was created by heavily changing the old Hull Castle and South Blockhouse. It was a triangle-shaped fort designed for artillery, located where the River Hull meets the Humber. The work cost a lot of money, over £100,000, and the Crown bought 29 acres of land for the expanded fort.

The Citadel was an irregular triangle, with strong walls and pointed sections called bastions at each corner. The old Castle and south blockhouse were built into the new fort's bastions. A wide ditch surrounded the Citadel on its eastern and western sides.

The military stopped using the Citadel by 1848. In 1863, it was sold, and by 1864, the site was cleared to make way for new industries and docks.

Sieges of Hull

Hull faced several attacks throughout its history. Around 1392, villagers from nearby Cottingham and Anlaby briefly attacked the town. They were angry that Hull was taking fresh water from sources near their villages. About 1,000 people threatened the town, but they eventually left without success.

The Pilgrimage of Grace

In 1536, during a large rebellion in northern England called the Pilgrimage of Grace, Hull was attacked. The rebels tried to get Hull to join them, but the town refused. After a five-day siege, the rebel forces, estimated to be between 2,000 and 3,000 strong, took control of the town on October 19, 1536.

A truce was later made between the rebels and the King. During this time, the King's power grew stronger. The Mayor of Hull, William Rogers, and other local people then managed to expel the rebel leader, John Hallam, from the town. However, the rebels quickly retook Hull and placed cannons in the harbor to protect it from sea attacks. The rebellion officially ended on December 2, 1536, when the King offered pardons.

The rebellion started again on January 10, 1537. John Hallam and others tried to sneak into Hull on market day to capture it from the inside, but they didn't have enough support from the townspeople. Hallam was captured. Another rebel, Francis Bygot, tried to besiege Hull in 1537. His forces destroyed some windmills outside Beverley Gate but could not take the town. As they retreated, they were attacked by Hull's forces. Hallam was later tried and hanged in Hull. In May 1537, Robert Constable, another rebel leader, was also found guilty of treason and hanged in Hull. His body was displayed in chains from Beverley Gate.

The English Civil War

In 1638, before the First Bishops' War with Scotland, King Charles I of England sent agents to inspect Hull's defenses. In 1639, it was reported that 1,000 men could defend the town. Charles I visited Hull in 1639 to see the fortifications and weapons. However, in April 1642, when the King returned to secure the arsenal (weapons store) at Hull, he was refused entry at Beverley Gate by John Hotham.

In July 1642, Charles I began the first siege of Hull. Ditches were dug around Hull to stop the attacking forces from getting too close. The Charterhouse, a building outside the walls, was torn down so the Royalists couldn't use it for defense. Hessle and Myton Gates were closed and blocked. More cannon batteries were set up outside Beverley, Myton, and North gates. There were small fights and cannon exchanges outside the walls. The siege ended when Parliamentarian forces successfully attacked the Royalist headquarters in Anlaby.

On September 2, 1643, a second siege of Hull began. Thomas Fairfax was now in charge of Hull's defenses, and the Royalist Earl of Newcastle led the attack. The ruins of the Charterhouse outside the north walls were turned into a fort for cannons. The land around Hull was flooded again to stop the Royalists from attacking. On September 16, the north Blockhouse of the Castle accidentally exploded due to its own gunpowder. Fighting continued outside the walls, with Royalists briefly taking control of defenses at Hessle Gate and Charterhouse before being forced back. On October 11, 1643, 1,500 men fought a seven-hour battle outside the walls, captured the Royalist positions, and ended the siege.

Images for kids

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |