Glen Davis Shale Oil Works facts for kids

The Glen Davis Shale Oil Works was a factory in the Capertee Valley, Australia, where oil was extracted from a special rock called oil shale. It operated from 1940 to 1952. This factory was the last place in Australia to produce oil from shale for many years. Between 1865 and 1952, it made about one-fifth of all the shale oil produced in Australia.

Contents

Building the Oil Works

The idea for the Glen Davis oil shale factory came about to help Australia's national security by making its own oil. It also aimed to create jobs for miners who were out of work. In 1936, the government asked companies to help develop the oil industry in the Glen Davis area.

A company called National Oil Proprietary Ltd. was formed to build and run the new factory. It received money from both the Australian and New South Wales governments.

Glen Davis was chosen for the factory because it was thought to have better mining conditions than the older site at Newnes. It also avoided the high cost of fixing the old Wolgan Valley railway.

Construction of the factory began in 1938, and it started working on January 3, 1940. Building the factory cost much more than expected, reaching £1,300,000.

Government Takes Control

During World War II, the oil produced at Glen Davis was very important for Australia's defense. In 1941, the factory made over 4.2 million imperial gallons of shale oil.

Because of the high costs and concerns about the project, the Australian government took over the management of the factory in December 1941. They bought out the private owners in 1949.

Experts from the United States suggested expanding the factory using new types of equipment called Renco or NTU retorts. However, Glen Davis decided to stick with its own 'modified Pumpherston' or 'Fell' retort design. From 1943 to 1945, the Glen Davis factory also refined about 2 million gallons of crude shale oil from another site near Lithgow.

Challenges and Closure

After the factory was expanded in 1946, it was supposed to make 10 million imperial gallons of petrol each year. But it faced a big problem: there wasn't enough oil shale being mined to keep the factory busy.

By 1947, the refinery section of the plant was only working for about 70 days in the first half of the year. The factory was losing money, and it was hard to find enough skilled workers because Glen Davis was in an isolated location. About 600 people worked there.

In 1948, a report showed that there wasn't enough shale left at Glen Davis to support further expansion. So, the government decided not to invest any more money.

In December 1950, the decision was made to close the factory. In 1951, its last full year, it produced only 1.45 million imperial gallons of oil and lost a lot of money. The main reason for the losses was the ongoing problem of not being able to mine enough shale.

The government stopped funding in 1952, and the Glen Davis factory closed on May 30. Some workers tried to keep the factory running by going on a 'stay down' strike, refusing to leave without pay. But the strike ended after 26 days without success.

There were disagreements among the workers' unions at Glen Davis. Some union leaders were accused of limiting how much shale miners could dig, which was called the 'darg'. This was said to be a reason for the low production. Others blamed the mining equipment or the factory's management for the problems.

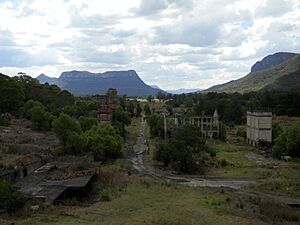

The closure was a big blow for the people who lived in Glen Davis. The government agreed to pay some compensation to help them. Most of the factory's movable parts were sold off in 1953. The town's population quickly dropped from about 2,000 to just 195 by late 1954, and Glen Davis became almost a ghost town. The parts of the factory that couldn't be moved became ruins.

Even though the factory was meant to help Australia make its own petrol, it only produced a very small amount compared to what the country used. By 1952, Australia used 638 million imperial gallons of petrol each year. The Glen Davis operation ended up having only a very small impact on Australia's economy.

Oil Shale and Water Supply

Two layers of oil shale were mined at Glen Davis. The main layer was called torbanite and was between 2 and 5 feet thick. Above it was a layer of clay, and then another layer of shale called the 'top' or 'secondary' seam.

The richer 'main seam' shale contained about 50% oil, which meant over 130 imperial gallons per long ton. The 'top' seam had much less, only about 8.5% oil. When both seams were mined together, the mixed shale averaged about 20% oil. The entire deposit was thought to hold about 2,000 million imperial gallons of oil. Mining both seams together allowed for using machines, even though it reduced the overall oil content.

A separate coal mine nearby supplied coal to the factory, which was used as fuel for its processes.

Water was also a challenge. Glen Davis only received 16 to 18 inches of rain per year. In dry times, there wasn't enough surface water. From March 1946, water was brought to the factory through a 105 km (65 mile) long pipeline from the Oberon Dam. This was unusual because it meant water from the Murray-Darling catchment was moved to an area east of the Great Dividing Range. Despite this, heavy rains in 1949 and 1950 caused flooding from the nearby Capertee River, affecting the factory.

How the Factory Worked

The mining and oil extraction complex covered a huge area of 55,000 acres.

Miners used a method called bord-and-pillar mining in the oil shale mine. About 170 miners worked there, and the mine was highly mechanized. Electric trains pulled the mined shale out of the mine on a narrow-gauge railway. The shale was then crushed and sent into large ovens called retorts.

The company first planned to use special tunnel ovens from Estonia and Germany. However, to save money, they decided in 1939 to use 64 modified Pumpherston retorts from the closed Newnes Shale Oil Works. There were some initial problems with these retorts, but they were eventually fixed. Another 44 similar retorts were added in 1946.

The retorts were heated by coal from the nearby coal mine. They were able to recover about 82% of the oil from the shale. This crude shale oil was then refined to make petrol, with a little over 50% of the crude oil turning into petrol.

The petrol was pumped through a 32-mile (51 km) long pipeline to storage tanks at Newnes Junction. From there, it was transported by train. The pipeline was made of 3-inch wide steel pipe. It crossed difficult terrain, including chasms and valleys.

The factory also had its own brickworks and power station.

Images for kids