Haytor Granite Tramway facts for kids

A section of the track as it appeared in 2005

|

|

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Dates of operation | 1820–1858 |

| Successor | Abandoned |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 3 in (1,295 mm) |

| Length | 10 miles (16 km) |

The Haytor Granite Tramway was a special railway built a long time ago. It was used to move heavy granite rocks from Haytor Down in Dartmoor, Devon, to the Stover Canal. What made it really unique was that its tracks were made from large pieces of granite, not metal! These granite tracks were shaped to guide the wheels of wagons pulled by horses.

This tramway was built in 1820. Back then, granite was very popular for building public buildings and bridges in growing cities across England. Around 1850, about 100 men worked at the quarries. But by 1858, the quarries closed because granite from Cornwall became cheaper to get.

Today, the Haytor rocks and quarries are protected. This means they are kept safe from new buildings or changes.

Contents

Moving Granite: How the Tramway Worked

The granite from the quarries near Haytor Rock was in high demand for building. But moving such heavy stone was a big challenge. This was before modern railways and good roads existed. Shipping by sea was a good option. The Stover Canal could carry goods from Ventiford to the Teign Navigation, which led to the sea.

The Haytor Tramway was built to carry the granite about 10 miles (16 km) to the canal. The tramway went downhill about 1,300 feet (400 m) to reach the Stover Canal. It was like an early type of railway called a "plateway." These used L-shaped metal plates to support and guide wagon wheels. But the Haytor Tramway used L-shaped granite blocks instead of metal. The raised part of the granite block guided the wagon wheels.

The wagons had plain wheels without flanges (the raised edges you see on train wheels). This meant they could be moved easily at the ends of the line without needing complex track switches. The track was 4 ft 3 in (1,295 mm) wide. At places where tracks joined, special "point tongues" were used to guide the wheels. These "tongues" were either made of oak wood or iron.

Empty wagons were pulled uphill to the quarries by teams of horses. But when the wagons were full of heavy granite, they rolled downhill by themselves, using gravity, all the way to the Stover Canal at Ventiford.

The route was carefully planned to go downhill smoothly towards the canal. This meant it followed the natural shape of the land. There was even a side track at Manaton Road. This might have been used to let wagons pass each other if they were going in opposite directions.

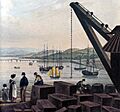

The Stover Canal was built between 1790 and 1792 by James II Templer. It was first used for clay. In 1820, it was extended to Teigngrace. From there, the granite went by canal boat to the New Quay at Teignmouth. This quay was built in 1827 for shipping granite by sea.

In 1829, James Templer's son, George Templer, faced money problems. He sold Stover House, the Stover Canal, and the Haytor Granite Tramway to Edward St Maur, 11th Duke of Somerset. George Templer later returned to Devon and became the main agent for the granite company.

The wagons were flat-topped and made of wood, with iron wheels that didn't have flanges. They were about 13 feet (3.96 m) long. Usually, about twelve wagons were pulled together. Horses pulled them from the front when going uphill and from the back when going downhill. An old sailor named Thomas Taverner wrote a poem about it:

Nineteen stout horses it was known,

From Holwell Quarry drew the stone,

And mounted on twelve-wheeled car

'Twas safely brought from Holwell Tor.

The "twelve-wheeled car" in the poem actually meant "twelve wagons with wheels." The wheels were about 2 ft (610 mm) wide and could turn freely on their axles.

Stover House itself was built with Haytor granite in 1781. Granite became more and more popular for building. The tramway was likely built because George Templer got a big contract to use the stone for London Bridge. Other famous buildings like parts of the British Museum and the old General Post Office in London also used Haytor granite. The very last time Haytor granite was used was for the Exeter War Memorial.

To split the granite, workers used a method called "feather and tare." This was better than older methods. First, they made a series of holes along where they wanted the rock to break. Then, they put two metal "feathers" (curved prongs) into the holes. A wedge-shaped metal "tare" was hammered between the feathers until the granite split.

The granite business wasn't always busy. Sometimes, no granite was produced or moved at all, like between 1841 and 1851. The quarries and tramway closed by 1858. Even though thousands of tons of granite were moved some years, cheaper granite from Cornwall made the business stop. The tramway was left unused. But because it was built so strongly and the granite wasn't worth much to recycle, much of it still exists today.

Building the Tramway

The tramway was built in 1820 without needing a special law from Parliament. It officially opened on September 16, 1820. George Templer managed the quarries and was likely in charge of building it. A description from that time shows how big an achievement it was:

On Saturday Mr. Templer, of Stover House, gave a grand fete champetre on Haytor Down, on the completion of the granite rail road. The company assembled at its foot on Bovey Heathfield, and in procession passed over it to the rock. A long string of carriages, filled with elegant and beautiful females, multitudes of horsemen, workmen on foot, the wagons covered with laurels and waving streamers, formed in their windings through the valley, an attractive scene to spectators on the adjacent hill. Old Haytor seemed alive: its sides were lined with groups of persons, and on its top a proud flag fluttered in the wind. Previously to returning to dine, Mr Templer addressed the assemblage in a short and energetic speech, which excited bursts of applause...

Many important people attended the opening, including Lord and Lady Clifford and Sir Thomas Dycke Acland.

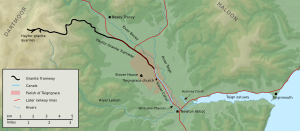

This tramway was very unusual in how it was built. It ran from the Haytor quarries all the way to Ventiford Quay on the Stover Canal. At first, it was about 7 miles (11 km) long. Later, it was extended to about 9 miles (14 km) or 10 miles (16 km), including all the side tracks. The hard granite stone was perfect for tracks because it could handle heavy loads.

The tramway had a main line going down to the Stover Canal. It also had six smaller branches or side tracks that went to different quarries. These side tracks were changed several times as needed. There were also some small hills cut through, small raised sections, and a few short bridges along the way. Because the "rails" were made of granite, large parts of the old tramway still exist today, especially near Haytor.

The Tramway's Path

In the late 1820s, people like Carrington wrote about how the tramway could be used as a path. People could walk or ride horses along it from Haytor to Teigngrace. This was because the tramway was often part of a road. Also, the granite wagons didn't move very often or very fast. So, it wasn't too dangerous for people to use the path.

Milestones were put up along the route. These stones marked the distance from Ventiford. The tramway never carried passengers, so these milestones might have just been a fun idea by George Templer. Four of these stones still exist today:

| Miles | Location |

|---|---|

| 3 | Between Pottery Road/Ashburton Road, Brimley |

| 4 | In a small group of trees south of the road from Bovey Tracey to Haytor near Lowerdown Cross |

| 5 | Yarner Wood |

| 6 | Across from the Bel Alp Hotel on the road to Haytor, soon after it reaches the open land at the eastern end of Haytor |

The tramway mostly carried granite. The company didn't want to spend money building special wagons for other things, like iron ore.

When the Moretonhampstead and South Devon Railway opened in 1866, the granite tramway had already been unused since 1858. However, the land owner, the Duke of Somerset, insisted that a side track and a crane be built. New exchange tracks were made at the 'Bovey Granite Siding,' about 1-mile (1.6 km) south of Bovey Tracey. But it was probably never used. About a mile of the old tramway's path was used for the new railway line.

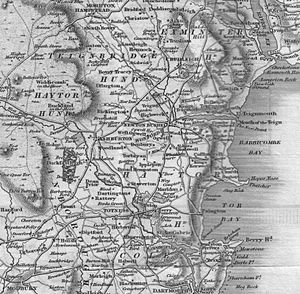

Old maps from the 1830s and 1860s show the path of the tramway.

The Templer Way

The Templer Way is a walking route today. It closely follows the path of the old Haytor Granite Tramway and the Stover Canal. It continues all the way to the New Quay in Teignmouth docks.

A great place to see the old granite tracks is where the route crosses a small road that leads to Manaton. This is just off the main road from Haytor to Bovey Tracey.

Once you are off the moor, you can see a good section of the tramway running through Yarner Wood. There is also a well-preserved five-mile (8 km) marker stone there. You can follow the granite track sections through the woods before the path goes back to the main Bovey Tracey road.

The tramway also crossed fields down to the road near the Edgemoor Hotel. You can still see some granite track pieces scattered on the hotel's lawn. Chapple Bridge was the first bridge on the tramway, crossing the Bovey leat (a man-made water channel). Later, another bridge was built when the second quarry opened at Holwell Tor.

Ventiford Cottages were built for the workers who worked on the tramway and canal. Stables were also kept here for the horses that worked both the canal and the tramway. You can clearly see granite blocks used in the construction of bridges along the Templer Way.

In late 2014, a part of the tramway that was previously unknown was found at its end point in Ventiford Basin.

Images for kids

-

A reconstructed section of flangeway track as used by Richard Trevithick showing striking similarities to the granite trackwork of the Haytor Tramway.

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |