Helene Nomsa Brath facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Helene Nomsa Brath

|

|

|---|---|

Helene Nomsa Brathwaite Street Naming

|

|

| Born |

Helene White

March 15, 1942 |

| Died | October 30, 2023 (aged 81) |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Community organizer, education reformer, activist, public speaker, artist |

| Spouse(s) | Elombe Brath |

| Children | 6 |

Helene Nomsa Brath was an amazing woman who worked hard for her community. She was a mother, wife, and a strong voice for education. Nomsa was also an artist and a public speaker.

For over 50 years, she worked alongside her husband, Elombe Brath. Together, they were important leaders in the Black Arts Movement. They also helped start the "Black is beautiful" movement in the 1960s. Nomsa was one of the first members of the Grandassa Models.

Helene Nomsa Brath is also known as Helene Nomsa Brathwaite.

Nomsa Brathwaite, along with Cinque Brathwaite and Kwame Brathwaite, helped create the Elombe Brath Foundation. This charity was started to honor her husband, Elombe Brath. Some of Nomsa's paintings were sold to help fund this important foundation.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Nomsa's birth name was Helene White. When she was a child, she had a special mentor named Goldie Seifert. Goldie was a very smart person. Her husband, Charles Seifert, was an expert in African and African American history.

Nomsa often said that Goldie taught her to love reading and thinking for herself. The Seifert family had a large collection of books. They even created a library in their home to help educate the Black community.

Making a Difference

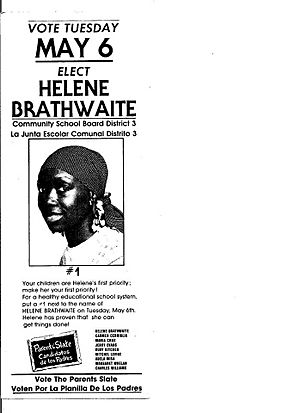

Helene Nomsa Brathwaite was known by several names, including Helene White and Nomsa Brath. She was married to Elombe Brath, who was a leader in the Black Arts Movement. For many years, Nomsa Brath was an important activist for education in New York City.

Champion for Education

From 1994 to 2003, Nomsa was a strong supporter of education reform. This means she worked to improve schools and how students learn. She was part of a discussion panel led by Hugh Bernard Price, who was the president of the National Urban League.

On this panel, Nomsa spoke for parents who wanted better education. This discussion was even shown on C-Span in 1997. For several years in the 1990s, she also represented a group called Partners for Reform in Math and Science (PRISM).

As an education reformer, Nomsa even decided to homeschool her fifth child. This child later scored very high on the SAT test. After homeschooling, he returned to public school and attended the Bronx High School of Science. This was a very good specialized high school in New York City. She also homeschooled her sixth child. After this, she volunteered to teach other children in her community.

Grandassa Models: Celebrating Black Beauty

In 1956, a group called the Jazz-Art Society was formed. It later became known as the African Jazz-Art Society & Studios, or AJASS. This group included organizers like Elombe Brath and Kwame Brathwaite.

AJASS started in Harlem and put on art shows and African cultural events. They were a big part of what later became the "Black Arts Movement." They also held jazz concerts. AJASS created the Grandassa Models with the idea that "Black Is Beautiful."

The Grandassa Models were inspired by Carlos A. Cooks and the African Nationalist Pioneer Movement (ANPM). This movement grew from Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA). The UNIA used to host a "Miss Natural Standard of Beauty Contest" each year.

Helene White was one of the first Grandassa Models. She was part of the "Naturally '62" beauty and fashion show. She even appeared as the cover girl on many jazz albums by Lou Donaldson. Her popularity grew, and she was featured on magazine covers in Africa. These magazines showed Black women in the United States wearing their hair naturally.

Grandassa models showed the natural beauty of African American women. They became beauty icons on magazine and album covers in the United States. Nomsa became a symbol for Black female empowerment in a cartoon strip in the New York Citizen Call Newspaper. This newspaper was an important voice for the Black community in the 1950s and 60s.

In the early 1980s, Nomsa Brath's popularity grew even more. Her husband, Elombe Brath, created a Grandassa Logo featuring her image for event flyers. These flyers were given out in Harlem for cultural and political events. They helped share the voice of the urban community. The "Naturally" beauty shows continued regularly through the 1980s and later became special commemorative events.

Making Schools Safer

Nomsa was also a strong supporter of removing asbestos from public schools in New York City. Asbestos is a natural material that was once used in building construction. However, it was later found to be dangerous and linked to serious illnesses.

In 1985, a legal journal called Journal of Law and Education wrote about Helene Brathwaite's work to remove asbestos from schools. Her efforts, along with others, helped close unsafe primary and grade schools in the 1970s. She was the President of the Parents Teacher Association and a leader of the Parents' Committee for two schools, PS 185/208. Her own children and their friends attended these schools, which were shut down because of asbestos dangers. It was known that 20% of New York City schools had asbestos.

Nomsa researched and learned about the dangers of asbestos. Her research helped her convince the school superintendent to close the schools. She also pushed for children to be bused to other schools in New York that were safe. Her strong advocacy showed what parents could achieve when they worked together. Since then, rules about asbestos in schools have become much stronger.

Today, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) sets and enforces federal laws about asbestos in school buildings. The Asbestos Hazard Emergency Response Act (AHERA) requires schools to inspect their buildings for asbestos. They also need to create plans to manage or reduce the risk of asbestos exposure. However, the law does not always require schools to remove asbestos if it is not damaged. It only needs to be removed if it is seriously damaged or might be disturbed during renovations.

The United Federation of Teachers, a group for teachers, wrote open letters to parents and educators. They said that Nomsa Brath, almost by herself, made the Board of Education accept how dangerous asbestos was. Scientists had known about these dangers for years.

The Central Park Five Case

Nomsa Brath was a key organizer in a very important case in New York City, known as the Central Park Jogger case. Five African American teenagers were accused in this case and became known as the Central Park 5.

Nomsa started a group called "Mother Love." This group was made up of mothers and female activists. They worked to support the innocence of the five teenagers. Nomsa and others believed the young men were innocent. The media at the time often showed sympathy for the jogger. The case caused a lot of division in New York City. Strong opinions and newspaper ads were published.

Many people felt the media was too quick to judge. "Mother Love" started a media campaign to push for justice. Nomsa's husband, Elombe, used his connections in television and radio to help share the story of the unfairness.

In 2002, the five young men known as the Central Park 5 were found innocent. This happened after Matias Reyes, a convicted criminal, confessed to the crime. DNA evidence proved he was guilty. He said he acted alone.

Nomsa's work and advocacy in this case are mentioned in several books. These include Black Women in America edited by Kim Marie Vaz, High-Profile Crimes by Lynn S. Chancer, and The Central Park Five: A Chronicle of a City Wilding by Sarah Burns. Sarah Burns is the daughter of Kenneth Lauren Burns, a documentary filmmaker. Sarah and Ken produced a 2012 documentary about the Central Park 5.

In a miniseries about the Central Park 5, directed by Ava DuVernay and released in April 2019, Nomsa Brath was played by actress Adepero Oduye. This series is called When They See Us.

In 2008, Nomsa had a stroke. This made it harder for her to continue her activism and painting.