Historical Panorama of Alabama Agriculture facts for kids

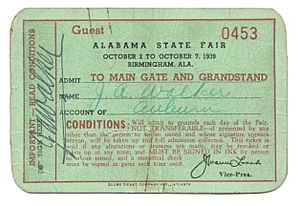

The Historical Panorama of Alabama Agriculture was a special series of large paintings. These paintings were ordered by the Alabama Extension Service. They were partly paid for by the Works Progress Administration (WPA). The murals were made for the 1939 Alabama State Fair, which happened in Birmingham.

Contents

Meet the Artist: John Augustus Walker

The job of painting these murals went to John Augustus Walker. He was a well-known artist from Mobile. Walker had already done other art projects for the WPA. He helped start the Mobile Art Guild. He was also known for his paintings and murals. You can find his art in homes and public buildings across Alabama and the Gulf Coast. He also designed Mardi Gras parade floats, costumes, and stage sets.

Why Were the Murals Created?

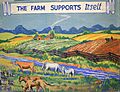

These murals show important times in Alabama's farming history. They start with the Native Americans. These paintings are very important items linked to Alabama Extension's long history with farming. They are also great examples of WPA art from the Great Depression era.

Walker was first asked to paint 29 murals. All of them were supposed to show farm life from Alabama's past. But because he didn't have enough time, he only finished ten. This project was one of many funded by the WPA. The WPA helped talented young artists like Walker, who was 37 at the time. It also encouraged people to stay interested in art during and after the Great Depression.

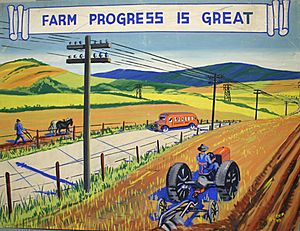

The murals were made to teach people as much as they were made to look nice. P. O. Davis, who was the Alabama Extension Director then, explained the purpose of the paintings. He said that "farming in Alabama, and in this nation, is changing. It's changing for the better and moving forward."

Alabama, Davis explained, was growing beyond just cotton. It was becoming a mix of cotton, other crops, and farm animals like livestock and chickens. He saw these murals and the fair exhibits as a way to celebrate the past. But they also helped farmers imagine a "vision of the future."

Davis wrote that the panorama would show "that Alabama agriculture is not only changing and improving. It is also ready to move forward in a big way, with efficiency and saving money."

Davis saw the murals as another way to teach. They were a way of "guiding farmers on what to do and how to do it."

State Fairs: A Big Deal for Learning

Back then, many ways of sharing information were new. So, state fairs were a great place to teach people. In the 1930s, during the Depression, state fairs were very popular. Thousands of Americans who were struggling financially could go there. They could forget their money problems and the worries about war in Europe for a little while.

Farm exhibits were a main part of these state fairs. Bruce Dupree, an art expert for the Alabama Cooperative Extension System, said:

- Fairgoers excitedly moved through buildings. These buildings often had poor lighting and no air conditioning.

- They saw prize-winning farm animals, colorful quilts, farm displays, baking contests, and canning demonstrations.

- In Alabama, each of the state's 67 counties had a space. They used it to show off local produce and specific farm industries.

Managing so many entries was often hard for fair planners. This led many of them to think of new ways to handle farm exhibits. The Historical Panorama of Alabama Agriculture was one of these new ideas.

The panorama was the idea of Warren Leech, the fair's vice president. He wanted to find a new and better way to show off Alabama farming. He planned to combine all the separate county exhibits into one big farm show.

Leech visited Alabama Extension Service Director P. O. Davis in Auburn. He wanted to talk about his ideas. Davis quickly saw this as a chance to show the important role of the Alabama Extension Service. He also wanted to highlight the Alabama Polytechnic Institute (now Auburn University) in helping the state's food and fiber industries.

Planning the Murals

Davis and other Alabama Extension leaders trusted Walker's artistic skills. In a report about the project in May 1939, it was called "in good hands." They thought it would be "unusually successful." Also, Extension workers who visited Walker in Mobile told Davis they were sure the panorama would "show Alabama agriculture in a very interesting way." They believed the whole series, especially if explained well, would "make a very strong impression" on visitors.

Alabama Extension planners were also happy with the price. With the WPA helping to pay, they felt they were getting murals worth $6,000 for "about the cost of the materials."

Even so, these planners didn't just leave everything to Walker's talent. They watched over the creative process throughout the project. Davis and other Alabama Extension workers worried about historical accuracy. For example, in a letter from April 18, 1939, Donald Robertson, the Alabama Extension Agricultural Editor, told Walker to change a male figure in a sketch about Native American farming life to a female. He wrote that "according to Indian Legend, the women did most of the field work while the men did the hunting and 'took life easy.'"

Robertson also suggested another picture. It would show "the arrival of women folks on the farm and perhaps one or two children. This would show the beginning of a well-rounded farm family."

Walker probably didn't expect so much close attention from Auburn. Not only his Extension Service sponsors but also employees from the U.S. Department of Agriculture were very involved in the planning. They gave detailed instructions. They even told him how to choose and place objects in front of the murals. For example, each mural was supposed to have a curtain border. In front of it, there would be a table filled with produce, farm tools, or household items to complete the artwork.

H.T. Baldwin, an employee with the Extension Exhibits Division of the USDA, gave instructions. He said, "The objects should be 100 percent related to the stage of development shown by the mural." Baldwin was one of several communication experts who traveled around the country. He advised state Extension services and checked the quality of Cooperative Extension art projects.

Baldwin also suggested putting more objects in the foreground. This would mean Walker wouldn't have to paint as much detail. Because of lighting, he also recommended that Walker use dull colors instead of oils, which would look shiny.

He also suggested that Walker include signs to help visitors "understand" the information in all the scenes. Baldwin also recommended painting the inside of the hall in Auburn University's school colors.

This project put a lot of stress on Walker, both physically and mentally. Besides his regular job, he was also dealing with a serious family illness. With only three weeks left before the fair opened, Walker worked very hard to finish. By then, the project had been cut down to 10 murals. The artist was also given full power to buy any materials needed. He could also fill the space left empty by the 10 unfinished paintings. He ordered 40 new spotlights, over 600 yards of curtain fabric, hundreds of feet of rope, and all the crepe paper he could find to cover the exhibit hall ceiling.

The finished murals were about 7.5 feet tall and 5.5 feet wide. They were painted with dry color on plain canvas. Also, since the murals were only meant to last for the fair, Walker used tempera paint. This is a water-based paint that is less durable. He usually preferred oil paints.

The Fair Was a Hit!

The fair and the panorama were very popular and successful. Huge crowds filled the midway, grandstand, and exhibit halls day and night.

Then-Governor Frank Dixon praised the fair and its planning. He called the fair "the best ever and a model for the entire nation to see."

The fair also made front-page news for five days in a row. It seemed to do what fairs usually did back then. It helped a tired state forget its money troubles and worries about the coming war in Europe. Also, the farming and industry exhibits seemed to interest people more than the rides and games.

What Happened Next?

Right after the Alabama State Fair, the murals were packed up. They were sent to Shreveport, Louisiana. They were displayed at the Louisiana State Fair, which took place from October 21–30, 1939.

Sometime after that, the murals were taken to Auburn University. They were stored in Duncan Hall, which was the main office for the Alabama Extension Service. They stayed there mostly untouched for 45 years. They were found again in the early 1980s. After being cleaned up, they were displayed in Foy Student Union on the Auburn University campus. After they were found, at least one person who admired Walker wanted to buy the murals from Auburn University. They wanted to return them to Mobile, where the artist was from.

However, the murals stayed in Auburn. In fact, as part of Auburn University's 150th anniversary celebration in 2006, the Alabama Cooperative Extension System, with Dupree's help, showed the paintings again. This was after more than 20 years. They held a public talk and display in the Foy Union Student Union Gallery.

The artist's son and grandchildren were there for the talk and exhibit. They greeted visitors and answered questions.

Images for kids

-

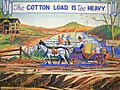

Originally, this painting was meant to show a poor "one-armed Confederate" veteran working in a field with eroded soil. This picture showed the opposite of what farming was supposed to be in the 20th century. Everything in the painting was meant to highlight this fact: a run-down plantation house, very eroded farm soil, a farm that only grew cotton, and a wagon loaded with supplies that should have been grown on the farm.

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |