History of education in Missouri facts for kids

The history of education in Missouri tells the story of schools and learning in the state. It covers more than 200 years, from the first small towns in the early 1800s until today. You'll learn about students, teachers, schools, and the rules that guided education.

Contents

Early Schools in Missouri

When Missouri became part of the United States in 1803, there were only a few small French settlements. These places had very limited schooling. By 1821, schools started appearing in towns like St. Louis, St. Charles, and Cape Girardeau. Some rural areas also had schools.

These early schools were often run by traveling teachers. They taught boys from families who could afford to pay a small fee. Sometimes, the teacher would even live with the family. By the 1830s, a few schools in the countryside taught both boys and girls. There were also about eleven schools just for girls. These schools taught basic reading and writing, plus skills for running a home.

In the 1830s to 1850s, state lawmakers tried to create big plans for schools. However, these plans were too complicated and expensive, so they never really started.

In 1818, Louis William Valentine Dubourg became the Catholic bishop of St. Louis. He started many new projects. A Catholic school, St. Louis Academy, opened that same year. It later became Saint Louis University, the first college west of the Mississippi River. Father Peter Verhaegen, a Jesuit leader, helped build up Catholic education in the West. He made the school fit the needs of people living on the frontier and even added a medical department.

Before the Civil War, Missouri was like many southern states. Public schools were not a big focus. Wealthy families often sent their children to private schools. Families with less money sometimes hired teachers together for their children. Public high schools did open in St. Louis and St. Joseph in the 1850s.

Growth After the Civil War (1860-1900)

After the Civil War, during a time called Reconstruction, new leaders in Missouri wanted to improve the state. They strongly supported building many more public schools. The state's new rules in 1865 called for a large network of public schools, including schools for Black children. The goal was for children to attend school for at least four months each year.

Under the leadership of Thomas A. Parker, the number of public schools grew quickly. From 1867 to 1870, the number of schools jumped from 48,000 to 75,000. Student enrollment also increased from 169,000 to 280,000. This included 9,100 Black students. About 59% of white children and 21% of Black children attended school in 1870.

Parker also helped teachers learn better ways to teach. New "normal schools," which trained teachers, opened in Kirksville and Warrensburg in 1870. A new state university was also founded in Columbia.

Most public schools at this time focused on basic reading, writing, and math. High schools were rare outside of big cities. Many private schools and colleges, often run by religious groups, also existed. St. Louis, led by superintendent William Torrey Harris from 1868 to 1880, created one of the best public school systems in the country. It even had the first public kindergartens. However, after 1872, public schooling became less important in rural Missouri.

In 1863, Anna Brackett became the principal of the St. Louis Normal School (now Harris-Stowe State University). She was the first female principal of a high school in the United States. Anna worked hard to make sure female students could get a good education to become professional teachers. She helped create rules for students to be a certain age and pass an entrance exam to get into the school.

Schools for African Americans

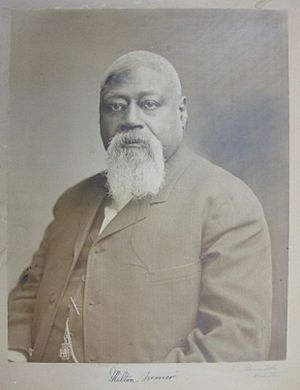

Before the Civil War, enslaved people in Missouri had almost no chance to go to school. A small number of free Black people in St. Louis had some small schools. During and after the Civil War, a group from New England called the American Missionary Association helped Black education in Missouri. They supported leaders like Colonel F. A. Seely and James Milton Turner. After 1864, these leaders traveled across the state and opened 32 schools for Black children.

During the war, the 62nd Colored Infantry regiment, made up mostly of soldiers from Missouri, started an education program for its soldiers. After the war, these soldiers raised money to start a school for Black students. This school, Lincoln Institute, opened in Jefferson City in 1866. It had Black students and both Black and white teachers. The state government also helped, giving money to train teachers for the new Black school system. The school was later renamed Lincoln University.

Learning About Engineering and Agriculture

In 1860, it was rare for colleges to teach engineering or farming. But this changed in 1862 when the Morrill Land-Grant Acts were passed. These laws gave land to states that created colleges with programs in engineering and scientific farming. After some delays, Missouri finally created the Missouri School of Mines and Metallurgy in Rolla and a new agricultural school at the University of Missouri in Columbia in 1870.

Education in the 20th Century

Older farmers often didn't see the benefit of school for their sons. They thought it took them away from learning farming skills at home. Around 1902, reformers started "educational trains" that traveled across the state. These trains showed farmers new scientific ways to farm and new technology. After 1914, the government created the "county agent system." This system provided ongoing support in each county to help farmers learn about new technology. The 4-H movement also grew in the 1920s to help educate young people in farming communities.

School Integration

In the early 1950s, Black students began to challenge the rules that kept them out of white-only schools. Some Black students were finally allowed into the University of Missouri. From 1950 to 1954, Black families tried to enroll their children in white schools in Kansas City and St. Louis. For example, 150 Black students tried to enroll in a white school in Kansas City, but they were turned away.

In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court made a very important decision called Brown v. Board of Education. This ruling said that separating students by race in schools was against the law. After this, Missouri's Attorney General announced that the state's school segregation laws were no longer valid.

However, some school districts in Missouri still refused to integrate. Schools in Charleston, Missouri, and other areas avoided integration until the mid-1960s. In many cases, Black students were sent to schools far from their homes, even if white schools were closer. Many libraries and parks also remained closed to Black students. Sadly, many Black teachers lost their jobs after integration began. For example, 11 Black teachers in Moberly were laid off in 1955.

By 1970, the Kansas City school district faced big problems. Many white and middle-class Black families moved out of the city. This meant the district had less money from taxes. The district relied more on money from the federal government, which required faster integration. Even with these efforts, desegregation in Kansas City happened too slowly. Most white students had already moved to the suburbs.

In the 1970s, a lawsuit challenged segregation in St. Louis city and suburban schools. In 1983, an agreement was reached. School districts in St. Louis County agreed to accept Black students from the city who wanted to attend. State money helped pay for transportation for these students. The agreement also encouraged white students from the county to attend special "magnet schools" in the city. This helped make the city's schools more diverse.

This plan greatly helped desegregate St. Louis schools. In 1980, 82% of Black students in the city went to all-Black schools. By 1995, only 41% did. In the late 1990s, the St. Louis voluntary transfer program was the largest of its kind in the United States, with over 14,000 students. This program is slowly ending and will finish after the 2030–2031 school year.

See also

- Education in Missouri

- Education in St. Louis

- Education in Greater St. Louis

- History of the University of Missouri

- History of Missouri

- History of education in the United States

- History of St. Louis

- Normal schools in the United States

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |