History of education in the United States facts for kids

The history of education in the United States tells us how people learned and were taught in America, from the 1600s to today. It covers both formal learning in schools and informal learning at home or in the community.

Contents

- Early American Schools (Colonial Era)

- Education in the New Nation (Federal Era)

- Education in the 1900s

- Education in the 2000s (21st Century)

- Images for kids

Early American Schools (Colonial Era)

Schools in New England

The very first schools in the thirteen original colonies opened in the 1600s. Boston Latin School, started in 1635, was the first public school and is still open today! The Mather School in Dorchester, Massachusetts, opened in 1639. It was the first free public school supported by taxes in North America.

At first, colonists taught children at home, through the church, or with apprenticeships. Schools became more important later. Many people in New England learned to read so they could read the Bible. This made literacy rates (how many people could read) much higher there.

By the mid-1800s, schools in New England took over many learning tasks that parents used to do.

All New England colonies required towns to set up schools. In 1642, the Massachusetts Bay Colony made "proper" education required. Other colonies followed this idea. In the 1700s, "common schools" started. These were one-room schools where students of all ages learned from one teacher. They were supported by the town but families still had to pay a small fee.

Larger towns also opened grammar schools, which were like early high schools. The most famous was the Boston Latin School. By the late 1700s, many of these were replaced by private academies. By the early 1800s, New England had many private high schools, now called "prep schools." These schools, like Phillips Andover Academy (1778) and Phillips Exeter Academy (1781), helped students get into top colleges.

Schools in the South

In the southern colonies, like those around the Chesapeake Bay, some basic schools started early. Wealthy families often hired private teachers for their children. Some even sent their sons to England or Scotland for school.

In Virginia, basic schooling for poor children was sometimes provided by the local church. Most rich parents taught their children at home with tutors or sent them to small private schools.

In the deep South (Georgia and South Carolina), private teachers ran most schools. Georgia had at least ten grammar schools by 1770. Many were taught by ministers. The Bethesda Orphan House also educated children. Many private teachers advertised their services in newspapers.

After the American Revolution, Georgia and South Carolina tried to start small public universities. Rich families still sent their sons to colleges in the North. In Georgia, public county academies for white students became more common. After 1811, South Carolina opened a few free "common schools" for reading, writing, and math.

After the American Civil War, during the Reconstruction era, the first public school systems supported by taxes were created in the South. Both white and Black students were allowed to attend, but schools were kept separate by race. (Only a few schools in New Orleans were mixed.)

Later, when white leaders regained control, they often gave much less money to public schools for Black students. This continued until 1954. That's when the U.S. Supreme Court said that separate schools for Black and white students were against the law.

In rural areas, public schooling usually stopped after elementary grades for both white and Black students. This was known as "eighth grade school." After 1900, some cities started high schools, mainly for middle-class white students.

Education for Girls and Women

The oldest school for girls that is still open in the U.S. is the Catholic Ursuline Academy in New Orleans. It was founded in 1727 by the Sisters of the Order of Saint Ursula. This academy was the first free school for young women. It was also the first school to teach free women of color, Native Americans, and enslaved women.

Tax-supported schooling for girls began in New England as early as 1767. Some towns were slow to support this new idea. For example, Northampton, Massachusetts, didn't want to pay taxes to help poor families. They only wanted to pay for a grammar school to prepare boys for college. Girls in Northampton didn't get public money for education until after 1800.

Historians note that in colonial times, reading and writing were different skills. Schools taught both. But in places without schools, writing was mainly taught to boys and a few rich girls. Men needed to read and write for their jobs. It was thought that girls only needed to read, especially religious books. This is why many colonial women could read but couldn't write their names, often using an "X" instead.

After 1740, education for wealthy women in Philadelphia changed. Instead of just teaching them manners, it encouraged them to learn more serious subjects like classical arts and sciences. This helped them improve their thinking skills and keep their high social status.

Non-English Schools

By 1664, when the English took over the New Netherland colony, most towns already had elementary schools. These schools were linked to the Dutch Reformed Church and focused on reading for religious lessons. The English later closed the Dutch-language public schools, turning some into private schools. The new English government didn't show much interest in public schools.

German settlements from New York down to the Carolinas also had elementary schools tied to their churches. Each religious group had its own schools. Early German immigrants were Protestant, and they wanted their children to read the Bible.

Later, after the 1848 revolutions and the Civil War, German Catholic and Lutheran groups started their own German-language church schools. This happened especially in cities with many German immigrants like Cincinnati and Chicago. The Amish, a small German-speaking religious group, don't believe in schooling past elementary level. They think it's not needed and could harm their faith.

Spain had small settlements in Florida, the Southwest, and Louisiana. There is little proof that they schooled girls. Church schools were run by Jesuits or Franciscans and were only for male students.

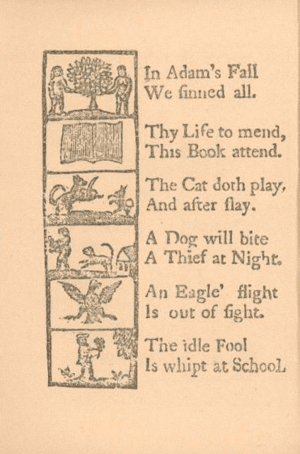

Early Textbooks

In the 1600s, colonists bought schoolbooks from England. By 1690, Boston publishers started reprinting the English Protestant Tutor as The New England Primer. This Primer focused on learning by heart. It taught Puritan children about their faith and how to behave. The Primer was very popular in colonial schools until Noah Webster's books came along.

Webster's "blue backed speller" was the most common textbook from the 1790s until 1836. Then, the McGuffey Readers became popular. Both series taught about civic duty and good behavior. They sold millions of copies.

Webster's Speller was designed to be easy to teach and followed a child's age. Webster believed students learned best when hard problems were broken into smaller parts. Students would master one part before moving to the next. He thought children learned in different stages. For example, he said not to teach a three-year-old to read; wait until they are five. His Speller started with the alphabet, then sounds, then syllables, then simple words, and finally sentences. It was a non-religious book. It ended with important dates in American history, from Columbus's arrival to the Battle of Yorktown in 1781.

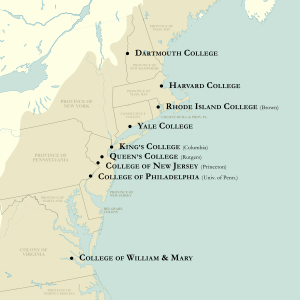

Colonial Colleges

Before 1800, higher education mainly trained men to become ministers. Doctors and lawyers usually learned through local apprenticeships.

Most early colleges were started by religious groups to train ministers. New England focused on reading the Bible, so Harvard College was founded in 1636 by the colonial government. It got money from the colony and donations. Harvard first trained ministers, but many graduates became lawyers, doctors, government leaders, or businessmen. It also brought new scientific ideas to the colonies.

The College of William & Mary was founded in Virginia in 1693. It received land and money from tobacco taxes. It was closely linked to the Anglican Church. James Blair, a leading Anglican minister, was its president for 50 years. This college was popular with wealthy Virginia families. It had the first law professor and trained many lawyers and politicians. Students studying to be ministers got free tuition.

Yale College was founded by Puritans in 1701. It moved to New Haven, Connecticut, in 1716. Conservative Puritan ministers wanted their own school to train ministers who followed their beliefs, as they felt Harvard was becoming too liberal.

New Side Presbyterians started the College of New Jersey in 1747, which later became Princeton University. Baptists started Rhode Island College in 1764, later renamed Brown University. Brown was known for welcoming students from different religious groups.

In New York City, Anglicans started Kings College in 1746. It closed during the American Revolution and reopened in 1784 as Columbia College, now Columbia University.

The Academy of Philadelphia was created in 1749 by Benjamin Franklin and other leaders. Unlike other colleges, it didn't focus on training ministers. It started America's first medical school in 1765, becoming America's first university. It was renamed the University of Pennsylvania in 1791.

The Dutch Reformed Church started Queens College in New Jersey in 1766, which later became Rutgers University. Dartmouth College, started in 1769 for Native Americans, moved to Hanover, New Hampshire, in 1770.

All these early colleges were small. They taught classical subjects like Greek, Latin, geometry, history, and logic. Students were usually under 17. There were no organized sports or fraternities, but many had active literary clubs. Tuition was very low.

There were no law schools in the colonies. Some young Americans studied law in London. Most aspiring lawyers learned by working with established lawyers or by "reading the law" on their own.

The first medical school in the colonies was started in 1765 by the Academy of Philadelphia (later the University of Pennsylvania). In New York, the medical department of King's College (now Columbia University) was started in 1767. In 1770, it gave out the first American M.D. degree.

Education in the New Nation (Federal Era)

The whole people must take upon themselves the education of the whole people and be willing to bear the expenses of it. There should not be a district of one mile square, without a school in it, not founded by a charitable individual, but maintained at the public expense of the people themselves.

After the American Revolution, northern states especially focused on education and quickly set up public schools. By 1870, all states had elementary schools supported by taxes. The U.S. had one of the highest literacy rates in the world then. Private academies also grew in towns, but rural areas had few schools before the 1880s.

In 1821, Boston started the first public high school in the United States. By the end of the 1800s, public high schools became more common than private ones.

Americans were influenced by European education reformers like Pestalozzi and Montessori.

Republican Motherhood

By the early 1800s, a new idea called republican motherhood became popular in cities. Writers like Lydia Maria Child said that women were best suited to teach and guide young children. They believed that a successful country needed good families, and women were key to raising good citizens.

By the 1840s, these writers helped improve and expand education for girls. Girls started learning subjects that were once only for boys, like math and philosophy. This idea of republican motherhood spread across the nation. It raised the status of women and supported the need for girls' education.

Wealthy southern families especially wanted their daughters schooled. Education was often seen as a good quality for marriage. These academies usually had a strong curriculum, teaching writing, math, and languages like French. By 1840, these schools helped create educated women ready for their roles in southern society.

School Attendance and Teachers

The 1840 census showed that about 55% of children aged five to fifteen attended primary schools or academies. Many families couldn't afford school fees or needed their children to work on farms. In the late 1830s, more private academies for girls opened, especially in northern states. Some offered a classical education, similar to what boys received.

Records from German immigrant children in Pennsylvania from 1771 to 1817 show that the number of children getting an education increased a lot. Also, more children went to school rather than being taught at home. In the South, most states did not allow Black people to go to school.

Teachers in the Early 1800s

Teaching young students was not a popular job for educated people. Adults became teachers without special training. Local school boards hired teachers, often young single women from local families, to save money. This began to change with "normal schools" starting in 1823. These two-year schools trained teachers. By 1900, most elementary school teachers in the North had gone to normal schools.

One-Room Schoolhouses

Since most people lived in rural areas with few students, many communities used one-room schoolhouses. Teachers taught students of different ages and abilities using the "Monitorial System." In this method, older or brighter students helped teach younger ones. This was also called "mutual instruction" or the "Bell-Lancaster method."

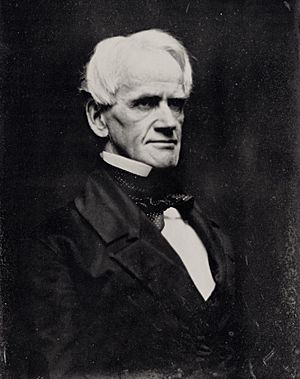

Horace Mann's Reforms

When Horace Mann became Massachusetts' secretary of education in 1837, he worked to create a statewide system of professional teachers. He based it on the "common schools" model from Prussia, where all students learned the same things in public classes. Mann focused on elementary education and teacher training. The common-school idea quickly spread across the North. Connecticut adopted a similar system in 1849, and Massachusetts made school attendance required in 1852.

Mann also introduced the idea of putting students in grades by age in 1848. Students were assigned to different grades based on their age and moved up together. Before this, classrooms often had students from 6 to 14 years old. He also used the lecture method, where teachers gave lessons instead of students teaching each other.

Mann believed that public education was the best way to turn children into disciplined, good citizens. Most states adopted a version of his system, especially the "normal schools" for training teachers. This led to what became known as the factory model school.

Compulsory School Laws

By 1900, 34 states had laws requiring children to go to school. Thirty states required attendance until age 14 or older. As a result, by 1910, 72% of American children attended school. Half of the nation's children went to one-room schools. By 1930, every state required students to finish elementary school.

Religion and Schools

In the 1800s, most Americans were Protestant. Many states passed laws called Blaine Amendments that stopped tax money from funding parochial schools (church-run schools). This was mainly aimed at Catholics, as many Catholic immigrants from Ireland arrived after the 1840s. Many Protestants believed Catholic children should go to public schools to become more "American."

By 1890, Irish Catholics had built many church schools across the Northeast and Midwest. They wanted these schools to protect their religion, culture, and language. Catholics and German Lutherans also started their own elementary schools. Catholic communities also raised money for colleges and seminaries to train teachers and religious leaders.

In 1925, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Pierce v. Society of Sisters that students could attend private schools to meet state attendance laws. This gave church schools official approval.

Schools for Black Students

After the Civil War, during the Reconstruction era, the Freedmen's Bureau opened 1,000 schools across the South for Black children. Black adults and children were very eager for schooling. The Bureau spent $5 million to set up these schools. By the end of 1865, over 90,000 freed people were enrolled. The schools taught a similar curriculum to those in the North.

Many teachers were well-educated women from the North, motivated by religion and the fight against slavery. About half the teachers were southern whites, one-third were Black, and one-sixth were northern whites. Most were women. Black teachers were often attracted to teaching because of good salaries during a tough economic time.

When Republicans gained power in the South after 1867, they created the first tax-funded public school systems. Black southerners wanted public schools for their children but did not demand mixed-race schools. Almost all new public schools were segregated, except for a few in New Orleans. After Republicans lost power in the mid-1870s, white leaders kept the public schools but cut funding for Black schools.

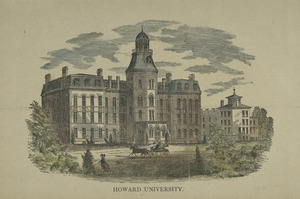

Almost all private schools and colleges in the South were strictly segregated by race. The American Missionary Association helped start several historically black colleges, like Fisk University and Shaw University. In the North, a few colleges accepted Black students. Northern churches and missionary groups also started private schools across the South to provide secondary education. By 1900, these groups ran 247 schools for Black students in the South, teaching 46,000 students. Important schools included Howard University, Fisk University, and Hampton Institute.

In 1890, Congress expanded the land-grant program to include federal money for state-sponsored colleges in the South. States had to have colleges for both Black and white students to get this funding.

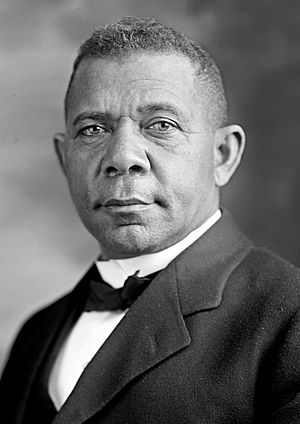

Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute and Tuskegee Normal School for Colored Teachers (led by Booker T. Washington) were very important. They set standards for "industrial education," which focused on practical skills.

Native American Missionary Schools

In the early 1800s, many evangelical Christians became missionaries. They wanted to convert non-Christians, and Native Americans were a close target. These missionaries believed Native Americans were "uncivilized" and needed help to become more like Anglo-Americans (white Americans).

Missionaries found it hard to convert adults, but easier with Native American children. They often separated children from their families to live at boarding schools. Here, missionaries tried to "civilize" and convert them. Missionary schools in the American Southeast started in 1817. Children learned basic subjects but were also taught to live and act like Anglo-Americans. Boys learned farming, and girls learned housework. They were taught that Anglo-American culture was better than their own Native American traditions.

The U.S. government provided some money for these schools, but missionaries were mainly responsible for running them. President James Monroe wanted the U.S. to give more money to private mission schools. In 1819, Congress started giving $10,000 a year to missionary groups. The Secretary of War, John C. Calhoun, wanted these funds used to teach Native American children Anglo-American culture, including farming for boys and domestic skills for girls. By 1824, the Bureau of Indian Affairs had approved 32 missionary schools, with 916 Native American children enrolled.

Influence of Colleges in the 1800s

In the 1800s, many small colleges helped young men move from farm life to city jobs. These colleges especially trained ministers, providing community leaders across the country. More exclusive colleges, like Harvard, became focused on children from wealthy families. They played a role in creating a powerful elite group in the Northeast.

Education in the 1900s

The Progressive Era (1890s-1930s)

The Progressive Era brought big changes to education. There was a huge increase in schools and students, especially in growing cities. After 1910, smaller cities also started building high schools. By 1940, half of young adults had a high school diploma.

Historians have different views on these changes. Some say the new school systems were too strict and tried to control working-class students. Others say these changes were needed to manage fast-growing schools and remove politics from them. The reforms aimed to create a more organized and efficient system. They introduced vocational training, doubled the time students spent in school, and focused more on the well-being of city youth.

Wealthy people in many cities led these reforms in the 1890s. They wanted to stop political parties from controlling local schools, which often led to jobs and contracts being given based on favors. Reformers created a system run by experts and required teachers to have special training. This helped more Irish Catholic and Jewish teachers get hired. The new focus was on giving students more opportunities. New programs started for students with physical disabilities. Evening recreation centers and vocational schools opened. Medical check-ups became common, and schools began teaching English to new immigrants. School libraries were also opened.

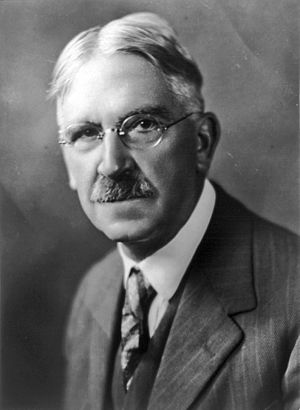

John Dewey and Progressive Education

John Dewey (1859–1952) was a leading thinker in education during this time. He was a philosophy professor at the University of Chicago and Columbia University. Dewey strongly supported "Progressive Education." He wrote many books about the important role of democracy in schools. He believed schools were not just for learning facts, but also for learning how to live. The goal of education, for Dewey, was to help students reach their full potential and use their skills for the good of society.

Dewey felt that education and schooling were key to creating social change. He believed that learning should help people understand and share in society's ideas. While Dewey's ideas were widely discussed, they were mostly put into practice in small experimental schools. Public schools, with their strict rules, were often not open to new methods.

Dewey saw public schools as undemocratic and narrow-minded. He preferred "laboratory schools," like those at the University of Chicago, which were open to new ideas and experiments. Dewey used these schools to test his ideas on learning, democracy, and how people learn.

Black Education in the Progressive Era

Booker T. Washington was a very important Black leader in education and politics from the 1890s until his death in 1915. He led Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. His advice and connections helped many other Black colleges and high schools, mostly in the South. Washington advised major charities like the Rockefeller and Rosenwald foundations, which gave money to Black schools. The Rosenwald Foundation helped build over 5,000 schools for rural Black students in the South.

Washington believed in progressive reforms, focusing on science, industrial, and agricultural education. This helped Black teachers, professionals, and workers get good jobs. He tried to work within the existing system and did not support protests against the segregated Jim Crow laws. However, he secretly helped fund legal challenges against laws that stopped Black people from voting.

The Gary Plan

The "Gary plan" was used in the industrial city of Gary, Indiana, by superintendent William Wirt from 1907 to 1930. This plan focused on using school buildings and facilities very efficiently. Over 200 cities, including New York City, adopted this model. Wirt divided students into two groups: one group used classrooms, while the other used shops, nature areas, the auditorium, gym, and outdoor spaces. Then the groups would switch.

Wirt also set up night schools, especially to help new immigrants learn English and American ways. Vocational programs, like wood shop, machine shop, and typing, were very popular with parents who wanted their children to get good jobs. By the Great Depression, most cities found the Gary plan too expensive and stopped using it.

Great Depression and New Deal (1929-1939)

Public schools were hit hard by the Great Depression. Tax money dropped, and local and state governments shifted funds to help people in need. School budgets were cut, and teachers sometimes didn't get paid. During the New Deal (1933–1939), President Franklin Roosevelt and his team didn't want to give direct federal money to public or private schools.

However, New Deal relief programs did build many school buildings. The Civil Works Administration (CWA) and Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) hired unemployed people to work on public buildings, including schools. They built or improved 40,000 schools and thousands of playgrounds. They also gave jobs to 50,000 teachers to keep rural schools open and teach adult classes in cities.

The New Deal also helped poor high school and college students. The CWA used "work study" programs to fund students. The National Youth Administration (NYA) created apprenticeship programs and camps to teach job skills. It was one of the first agencies to specifically try to enroll Black students. The NYA expanded work-study money to reach up to 500,000 students per month.

Growth of High Schools

In 1880, American high schools were mainly for students going to college. But by 1910, they became a key part of the public school system, preparing many students for work after graduation. The number of students grew rapidly, from 200,000 in 1890 to almost 2,000,000 by 1920. This meant 32% of youth aged 14 to 17 were in high school. Graduates found jobs in the fast-growing office sector. Cities built many new high schools. Few were in rural areas, so some families moved closer to towns for their teenagers to attend. After 1910, vocational education was added to train skilled workers for industries.

In the 1880s, high schools started becoming community centers. They added sports, and by the 1920s, they built gyms that attracted large crowds to basketball games, especially in small towns.

College Preparation

Before 1920, most secondary education focused on preparing a few students for college. Greek and Latin were very important. However, some, like Abraham Flexner, argued for less emphasis on classical subjects.

Before World War I, German was a popular second language to study. But during the war, anti-German feelings grew in the U.S. French then became the preferred second language until the 1960s, when Spanish became popular due to the increase in Spanish-speaking people in the U.S.

Growth of Human Capital

By 1900, educators believed that schooling beyond elementary grades would create better citizens and leaders for a modern economy. The U.S. commitment to widespread education past age 14 was unique compared to Europe for much of the 1900s.

From 1910 to 1940, high schools grew in number and size, reaching more students. In 1910, 9% of Americans had a high school diploma; by 1940, it was 50%. This growth was helped by public funding, open access, equal opportunities for boys and girls, local control, and a focus on academics. European countries had more exclusive education systems.

American post-elementary schooling taught general skills that could be used in many jobs and places. This was important because the economy was changing quickly.

Public schools were funded and managed by local districts, unlike the centralized systems in Europe.

Teachers and Administrators

Early school leaders focused on discipline and memorization. School principals made sure teachers followed these rules. Students who caused problems were expelled.

The growth of high schools was supported by local communities. After 1916, the federal government started funding vocational education. States and religious groups usually funded teacher training colleges, called "normal schools." These gradually became four-year state colleges after 1945.

Teachers started organizing in the 1920s and 1930s. The National Education Association (NEA) grew a lot, representing teachers and staff. The American Federation of Teachers (AFT) was based in cities and worked with labor unions. The NEA saw itself as a professional group, while the AFT identified with working-class people and unions.

Higher Education in the 1900s

At the start of the 1900s, there were fewer than 1,000 colleges in the U.S. with 160,000 students. The number of colleges grew very fast in the late 1800s and early 1900s. This was partly due to Congress's land grant programs. Rich people also gave money to start many of these schools. For example, wealthy donors started Johns Hopkins University, Stanford University, Carnegie Mellon University, Vanderbilt University, and Duke University. John D. Rockefeller funded the University of Chicago.

Land Grant Universities

Each state used federal money from the Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Acts of 1862 and 1890 to create "land grant colleges." These schools focused on agriculture and engineering. The 1890 act required states with segregation to also provide land grant colleges for Black students, mainly for teacher training. These colleges helped rural areas develop.

Iowa State University was the first school whose state officially accepted the Morrill Act in 1862. Other universities like Purdue University, Michigan State University, and Cornell University followed. Few graduates became farmers, but they played a big role in the food industry.

Engineering graduates helped with fast technological development. The land-grant college system produced agricultural scientists and engineers. These people were crucial for the growth of government and business from 1862 to 1917. They built the foundation for America's strong education system and technology-based economy.

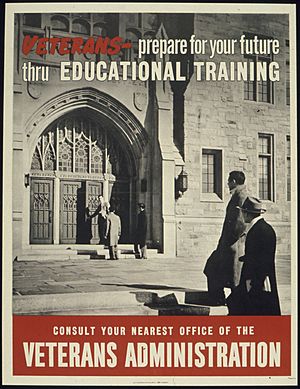

The GI Bill

In 1944, during World War II, Congress passed the GI Bill. This program helped millions of veterans go to college by paying for tuition and living expenses. The government gave veterans between $800 and $1,400 each year to attend college. This covered a large part of their costs and allowed them to afford life outside of school. The GI Bill made many people believe that a college education was necessary. It allowed ambitious young men who might have gone straight to work to attend college instead. Veterans were 10% more likely to go to college than non-veterans during this time.

In the early years, most college campuses became mostly male because of the GI Bill, as only 2% of wartime veterans were women. But by 2000, more female veterans were attending college and graduate school than men.

The Great Society and Education

When liberal politicians gained control of Congress in 1964, they passed many Great Society programs supported by President Lyndon B. Johnson to increase federal support for education. The Higher Education Act of 1965 created federal scholarships and low-interest loans for college students. It also helped academic libraries, new graduate centers, technical institutes, and community colleges. Another law that year helped dental and medical schools. On an even larger scale, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 started sending federal money to local school districts.

Segregation and Integration

For much of U.S. history, education was separate (segregated) or only available based on race. Early mixed-race schools, like the Noyes Academy in New Hampshire (1835), often faced strong local opposition. Before the American Civil War, most African Americans received little to no formal education. Some free Black people in the North learned to read and write.

In the South, where slavery was legal, many states had laws against teaching enslaved African Americans to read or write. A few learned on their own or from white friends, but most could not. Schools for free Black people were private, as were most limited schools for white children. Poor white children usually didn't go to school. Wealthy families hired tutors or sent their children to private academies and colleges.

During Reconstruction, Black freedmen and white Republicans in Southern state governments passed laws creating public education. The Freedmen's Bureau helped set up schools in many areas. Except for a few mixed schools in New Orleans, schools were separated by race. By 1900, over 30,000 Black teachers had been trained in the South, and the literacy rate for Black people rose to over 50%.

Many colleges were started for Black students. Some were state schools like Booker T. Washington's Tuskegee Institute. Others were private schools supported by Northern missionary groups.

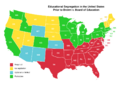

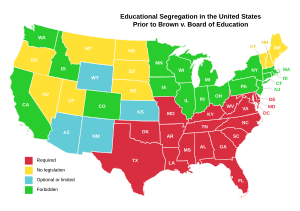

In the 1800s, the Supreme Court generally did not rule in favor of challenges to segregation. The case of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) said that separate schools were legal as long as they were "equal" (the "separate but equal" rule). However, Black students rarely received equal education. Their schools often had less money, old buildings, and poor textbooks.

Starting in 1914, Julius Rosenwald, a rich person from Chicago, created the Rosenwald Fund. This fund provided money to help build new schools for African American children, mostly in the rural South. He worked with Booker T. Washington and architects at Tuskegee University to create model school plans. With the rule that both Black and white communities had to raise money, Rosenwald helped build over 5,000 schools across the South.

The Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s showed how unfair segregation was. In 1954, the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education ruled that separate schools were always unequal and against the law. By the 1970s, segregated school districts in the South had mostly disappeared.

Integrating schools was a long process. In 1957, federal troops had to enforce the integration of Little Rock Central High School in Little Rock. President Dwight D. Eisenhower took control of the National Guard when the governor tried to stop integration. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, integration continued with different levels of difficulty. Some cities tried to overcome segregation caused by where people lived by using forced busing. This meant sending students to schools outside their neighborhoods. This method caused resistance in many places, including northern cities.

By 1970, technical equality in education had been achieved. However, full equality is still a goal. The federal government's efforts to integrate schools slowed down in the mid-1970s. School integration reached its highest point in the 1980s and has been slowly decreasing since then.

Education After 1945

In the mid-1900s, there was a strong interest in helping children be creative. This changed how children played and how homes, schools, parks, and museums were designed. Children's TV shows tried to encourage creativity. Educational toys that taught skills became popular. Schools started focusing more on arts and science. School buildings were designed with students in mind, not just as grand monuments.

However, in the 1980s, the focus shifted to test scores. Schools were forced to spend less time on art, drama, music, and history if these subjects weren't on standardized tests. This was because of laws like the "No Child Left Behind Act," which labeled schools as "failing" if their test scores were low.

Inequality in Education

The Coleman Report in 1966, based on a lot of data, caused debate about how much schools affect student success. It suggested that a student's family background and wealth were more important for their education than how much money a school had. Coleman found that by the 1960s, Black schools generally received almost equal funding. He also found that Black students did better in mixed-race classrooms.

The quality of education in rich and poor areas is still a topic of debate. While middle-class African-American children have made good progress, poor minority students still face challenges. Since school systems often rely on property taxes, there are big differences in funding between wealthy suburbs and poorer inner-city areas or small towns.

Special Education

In 1975, Congress passed Public Law 94–142, the Education for All Handicapped Children Act. This important law made free, appropriate education available to all eligible students with a disability. The law was updated in 1986 to include younger children. In 1990, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) changed the term "handicap" to "disabilities" and expanded its definitions. More changes were added to IDEA in 1997.

Reform Efforts in the 1980s

In 1983, the National Commission on Excellence in Education released a report called A Nation at Risk. After this, some people called for tougher academic standards. They wanted more school days, longer school days, and higher testing standards. English scholar E.D. Hirsch criticized progressive education. He argued for focusing on "cultural literacy"—the facts and texts that he said are essential for understanding basic information and communicating. Hirsch's ideas are still important in some groups today.

By 1990, the United States spent 2% of its budget on education, compared to 30% on support for older people.

Education in the 2000s (21st Century)

Current Trends

As of the 2017–18 school year, there were about 4,014,800 K-12 teachers in the United States. This included teachers in public schools, public charter schools, and private schools.

Education Policy Since 2000

"No Child Left Behind" was a major national law passed in 2002. It required states to measure student progress and penalize schools that didn't meet goals on standardized math and language tests. By 2012, many states were given exceptions because the goal of 100% of students being "proficient" by 2014 was not realistic.

By 2012, 45 states had stopped requiring the teaching of cursive writing. Today, you can often find reports of a student's progress online, instead of just getting paper report cards.

By 2015, there were so many criticisms of "No Child Left Behind" that Congress removed all its national features. The remaining parts of the law were given back to the states to manage.

Starting in the 1980s, leaders in government, education, and business identified key skills needed for the changing, digital workplace and society. 21st century skills are higher-level abilities and ways of learning that are considered important for success today. These include analytical thinking, solving complex problems, and teamwork. Many schools are changing their learning environments and lessons to include more active learning (like experiential learning) to help students develop these skills.

Images for kids

-

A picture of Harvard College from 1768, made by Paul Revere

-

A historical marker in Hilham, Tennessee for the Fisk Female Academy, founded in 1806

-

Horace Mann wanted to make education like the Prussian model.

-

The Freedmen's School on Edisto Island, South Carolina, around 1865.

-

Howard University was founded in 1867, one of many historically black colleges and universities started after the American Civil War.

-

St. Mary's Mission in Kansas, founded in 1847, aimed to convert and assimilate Potawatomi children.

-

John Dewey was a major leader in progressive education.

-

Booker T. Washington, a leading figure for Black Americans in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

-

Stephen F Austin Junior High in Galveston, Texas, built by the Works Progress Administration in 1939.

-

Carnegie Mellon University is one of many universities started by wealthy donors in the late 1800s.

-

Iowa State University was the first school to accept the Morrill Act in 1862.

-

Segregation laws in the United States before the Brown v. Board of Education ruling.

-

Monroe Elementary School, a formerly segregated school in Topeka, Kansas, important in the Brown v. Board of Education case.

-

Little Rock Central High School became a key place during the Little Rock Integration Crisis.

-

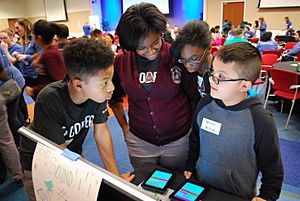

Students in Richmond taking part in an Hour of Code event.

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |