History of Missouri facts for kids

The history of Missouri is a story of many changes, from ancient times to today. It began with indigenous people living here around 12,000 BC. Later, in the 1600s, French explorers arrived and set up small towns. In 1803, the United States bought this land from France as part of the Louisiana Purchase. Missouri became a state in 1821 after the Missouri Compromise, which allowed slavery.

After 1820, many people moved to Missouri. They used the rivers for travel and trade, especially around St. Louis. European immigrants, like Germans, came to live here. After the Civil War, Missouri's economy grew in different ways. Railroads, especially in Kansas City, helped farmers in the west. In the 1900s, Missouri modernized its government and economy. Today, services like medicine, education, and tourism are important, but farming is still a big part of the state.

Contents

- Early European Exploration and Settlement: 1673–1803

- Missouri Becomes a Territory and State: 1804–1860

- Civil War and Reconstruction: 1861–1874

- Growth and Modernization: 1875–1919

- Growth, Hard Times, and War: 1920–1945

- Modern Missouri: 1946–Present

- Images for kids

Early European Exploration and Settlement: 1673–1803

In May 1673, a French priest named Jacques Marquette and a French trader named Louis Jolliet traveled down the Mississippi River. They explored the area that would later become Missouri.

In the late 1680s, the French wanted to settle central North America. They hoped to trade and stop England from taking over the land. In 1700, a Jesuit priest named Pierre Gabriel Marest started a mission on the west side of the Mississippi River. He settled with French people and the Kaskaskia tribe, who wanted protection from the Iroquois. The Mississippi and Missouri rivers were the main ways to travel and communicate in this region.

In the 1710s, France wanted to develop Louisiana more. They built Fort de Chartres north of Kaskaskia as a main base. They also sent groups to look for lead and silver in what are now Madison, St. Francois, and Washington counties. In 1722, Étienne de Veniard, Sieur de Bourgmont came to Missouri. He was sent to protect French trade on the Missouri River from Spanish influence. In 1723, Bourgmont built Fort Orleans in present-day Carroll County. He made agreements with Native American tribes along the Missouri River. The fort was soon left because of financial problems. In 1731, France took back control of Louisiana. During the 1730s and 1740s, France's control over Missouri was weak. There were no permanent towns on the western bank of the Mississippi River.

French settlers stayed on the east bank of the Mississippi until 1750. That's when the new town of Ste. Genevieve, Missouri was built. Ste. Genevieve grew slowly at first because it was on a flat, muddy area. In 1752, only 23 people lived there. They were farmers who grew wheat, corn, and tobacco.

Spanish Control and New Towns

A war between France and England, called the French and Indian War, started in 1754. It was about who would control the Ohio Valley. England won, and France lost all its land. In November 1762, France gave Spain control of Louisiana in the Treaty of Fontainebleau.

Meanwhile, the French governor of Louisiana gave a trade deal to Gilbert Antoine de St. Maxent and Pierre Laclède. In August 1763, Laclede and his stepson Auguste Chouteau left New Orleans for Missouri. In February 1764, they started St. Louis on high land overlooking the Mississippi. Many French settlers from east of the Mississippi moved to Missouri to avoid British rule.

| Settlement | Year Founded |

|---|---|

| Mine La Motte | 1717 |

| Ste. Genevieve | 1750 (earlier settlement 1735-1785) |

| St. Louis | 1764 |

| Carondelet | 1767 |

| St. Charles | 1769 |

| Mine à Breton | 1770 (earlier settlement 1760-1780) |

| New Madrid | 1783 (earlier settlement 1789) |

| Florissant | 1786 |

| Commerce | 1788 |

| Cape Girardeau | 1792 |

| Wolf Island | 1792 |

When Spain took control of Louisiana again, Ste. Genevieve and St. Louis were growing. Many French people moved there from British-held Illinois. Ste. Genevieve often had floods, but in the 1770s, it had about 600 people, a bit more than St. Louis. Ste. Genevieve people farmed and traded furs. St. Louis focused mostly on fur trading, which sometimes caused food shortages. This led to its nickname 'Paincourt', meaning 'short of bread'. South of St. Louis, a smaller town called Carondelet was started in 1767, but it never grew very big. In 1769, Louis Blanchette started a trading post on the Missouri River. This later became the town of St. Charles.

Spanish officials managed the colony. They often had to follow local French customs. In the 1770s, Spanish officials also dealt with British traders and unfriendly Native American tribes.

To reduce British influence, Spain tried to get more French settlers to move to Missouri. In 1778, Spain offered land and supplies to Catholic immigrants. But few people took the offer. Spain had more success helping the American rebels in the American War of Independence. Spanish officials in St. Louis and Ste. Genevieve helped supply George Rogers Clark during his 1779 campaign.

However, Spain's help came with a cost. In June 1779, Spain declared war on England. News reached Missouri in February 1780. By March 1780, St. Louis was warned of a British attack. The Spanish government started building a fort called Fort San Carlos. In late May, a British war party attacked St. Louis. The town was saved, but 21 people died, 7 were hurt, and 25 were taken prisoner.

After the American war, the Peace of Paris was signed. Spain kept Louisiana. Many American immigrants started crossing into Missouri from the east. Instead of stopping them, Spanish leaders encouraged it. They wanted to make the province economically successful.

In 1789, Spanish leaders in Philadelphia encouraged George Morgan, an American officer, to start a colony in southern Missouri. It was called New Madrid. The colony started well, but Louisiana's governor, Esteban Rodríguez Miró, didn't like it. He thought it wouldn't be loyal to Spain. Early American settlers left, and New Madrid became mostly a hunting and trading post.

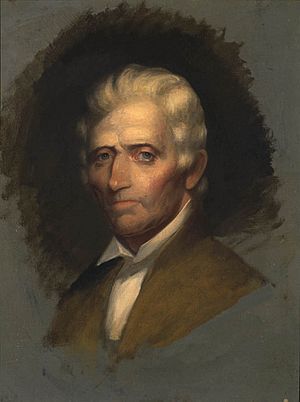

In the early 1790s, governors Miró and Francisco Luis Héctor de Carondelet were not keen on American immigration. But when the Anglo-Spanish War started in 1796, Spain again needed more settlers to defend the region. Spain offered free land and no taxes in its territory. Americans responded, and many moved there. One of these American pioneers was Daniel Boone, who settled with his family.

To govern Missouri better, Spain divided it into five areas in the mid-1790s. These were St. Louis, St. Charles, Ste. Genevieve, Cape Girardeau, and New Madrid. Cape Girardeau was the newest, founded in 1792 by trader Louis Lorimier. St. Louis was the capital and trade center. By 1800, its area had almost 2,500 people. Other towns in the St. Louis area included Florissant (settled 1785) and Bridgeton (settled 1794). These towns were popular with immigrants from the United States.

However, these American settlers changed Missouri greatly. By the mid-1790s, Spanish officials realized that American Protestant immigrants were not interested in becoming Catholic or being loyal to Spain. Despite a short attempt to only allow Catholic immigrants, the large number of Americans changed the way of life and even the main language of Missouri. By 1804, more than three-fifths of the people were American. Spain saw little benefit from the colony. So, in 1800, Spain gave Louisiana, including Missouri, back to France. This was made official in the Third Treaty of San Ildefonso.

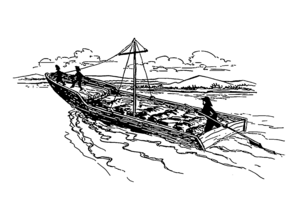

By 1800, most people in Upper Louisiana lived in a few towns along the Mississippi River in what is now Missouri. Travel between towns was by river. Most people farmed to feed themselves, but they also raised animals. Fur trading, lead mining, and making salt were also important jobs in the 1790s.

The settlers in Spanish Missouri were French, and the Catholic Church was a big part of their lives. Until 1773, Missouri churches did not have full-time priests. Traveling priests from the east side of the Mississippi served the people. In the 1770s and 1780s, Ste. Genevieve and St. Louis got their own priests. Protestant services were not allowed, but Protestant preachers often visited secretly. Rules against Protestants living there were rarely enforced. Historian William E. Foley said that Spanish Missouri had a "de facto form of religious toleration" (meaning, it was tolerated in practice).

There were no nobles or royalty. The highest class was based on wealth and included French-Creole merchants. Below them were skilled workers, then laborers like boatmen, hunters, and soldiers. At the bottom were free black people, servants, and coureur des bois (French-Canadian fur traders). Black and Native American slaves were the lowest class.

Women in the region did many household tasks. This included preparing food and making clothes. French women were known for their cooking, which mixed French dishes with African and Creole foods like gumbo. Colonists also ate local meats like squirrel, rabbits, and bear. But they preferred beef, pork, and fowl. Most food was local, but sugar and alcohol were imported until later Spanish times. Malaria was a problem, especially in low-lying towns like Ste. Genevieve.

The number of enslaved black people in the region was large. In 1772, almost 38 percent of residents were of African descent. By 1800, this number went down, but it was still almost 20 percent of the total population.

Missouri Becomes a Territory and State: 1804–1860

New American Control and the War of 1812

Even though Napoleon and France took control of Spanish Missouri in 1800, it was a secret. Spanish officials still controlled Missouri and all of Louisiana. In 1802, France tried to take back control of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti). This was a step to control New France. But disease and the ongoing Haitian Revolution stopped the French. In October 1802, French officials stopped foreign trade at New Orleans. This led the United States to try to buy New Orleans from France in March 1803. But France's defeat in Haiti and Napoleon's need for money to fight Britain led him to sell all of Louisiana, including Missouri, to the United States. This was the Louisiana Purchase.

News of the sale reached Missouri in August 1803. The purchase was first divided into two parts. Land north of the 33rd parallel (including Missouri) became the District of Louisiana. It was added to the Indiana Territory. Most Missourians didn't like this. They said their capital, Vincennes, Indiana, was too far away. They also felt slavery was not protected. In 1805, Congress changed the territory. They created the Louisiana Territory with its government in St. Louis. At first, people living there had no say in the government. The governor and three judges worked in St. Louis.

The land south of the 33rd parallel became the Territory of Orleans. It became the state of Louisiana in 1812. The Louisiana Territory was then renamed the Missouri Territory. That year, the territory's status was raised. People living there could now vote for lawmakers. Citizens chose one representative for every 500 free white males for a House of Representatives. The upper house, the Legislative Council, had nine men chosen by the President. The territory also elected a delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives.

The governors of the territory were generally good at their jobs, except for the first one, James Wilkinson. From 1803 to 1805, Amos Stoddard was the main leader of the District of Louisiana. In 1805, President Jefferson named James Wilkinson as the first territorial governor. But Wilkinson was a traitor. He was part of the Burr conspiracy to start a revolution in the West. Wilkinson didn't make many friends in Missouri. He tried to steal business from French fur traders. He was removed from his job in March 1807. Meriwether Lewis, a hero from the Lewis and Clark Expedition, replaced him.

Meriwether Lewis was not well-suited to be governor. He did an okay job, but his new fame made him moody. He died in 1809 on a trip to Washington, D.C. Lewis's replacement, Benjamin Howard, was a Congressman from Kentucky. He served well from 1810 to 1813, especially during the War of 1812. Howard resigned when he was promoted to general in the U.S. Army. The last territorial governor, William Clark, was also famous from the Lewis and Clark expedition. He served the territory well from 1813 to 1821. He treated settlers and Native Americans fairly.

Soon after the Louisiana Purchase, the U.S. Army built forts to control the territory and help trade. Fort Bellefontaine was built near St. Louis in 1804. To influence the Osage tribe, the government built Fort Osage near present-day Sibley.

Missouri was on the western edge during the War of 1812. No big battles between British and Americans happened there. But in the years before and during the war, there were fights between Native Americans and settlers. In 1811, Governor Harrison attacked Shawnee Chief Tecumseh at the Battle of Tippecanoe. This caused fighting between tribes east of the Mississippi and American settlers. Few tribes in Missouri fought against settlers during the war. But Missouri settlers were attacked by Sac and Fox groups from Illinois.

Almost all attacks happened in central Missouri, north of the Missouri River, or along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. Places attacked included Charette, Cote sans Dessein, Femme Osage, Fort Cap au Gris, Portage des Sioux, and St. Charles. Federal troops left Fort Osage in 1813 for the war. This left Fort Bellefontaine as the only federal outpost. Several fights happened in Missouri, including the Battle of the Sink Hole near present-day Old Monroe on May 24, 1815. This was one of the last battles of the war.

During the war, Missouri created militia units called Missouri Rangers. They patrolled the Missouri and Mississippi rivers. Local citizens formed these units because they felt the federal government wasn't doing enough to defend the territory. They mostly defended the area, but sometimes they were part of larger attacks.

Becoming a State and Early Politics

| Population of Missouri | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1810 | 20,845 | — |

| 1820 | 66,586 | +219.4% |

| 1830 | 140,455 | +110.9% |

| 1840 | 383,702 | +173.2% |

| 1850 | 682,044 | +77.8% |

| 1860 | 1,182,012 | +73.3% |

| 1870 | 1,721,295 | +45.6% |

| 1880 | 2,168,380 | +26.0% |

| 1890 | 2,679,184 | +23.6% |

| U.S. Census | ||

In November 1818, Missouri's territorial government asked to become a state. They sent the request to Congress in December 1818. But this request caused a national argument. It was about the balance between slave and free states. Missouri wanted to be a slave state. But members of Congress who were against slavery added changes to the law. In 1820, the Missouri Compromise allowed Missouri to join the Union as a slave state. Maine, a free state, also joined to keep the balance. The Compromise also said that the rest of the Louisiana Territory north of the 36°30′ line would be free from slavery. That same year, Missouri adopted its first constitution. In 1821, Missouri became the 24th state. The state capital was temporarily in Saint Charles until a permanent one could be built. Missouri was the first state west of the Mississippi River to join the Union. The capital moved to Jefferson City in 1826.

When Missouri became a state, its western border was a straight line from Iowa to Arkansas. This was based on where the Kaw River met the Missouri River in Kansas City. Land in what is now northwest Missouri was given to the Iowa and the combined Sac and Fox tribes. White settlers, especially Joseph Robidoux IV, started moving onto this land. So, William Clark convinced the tribes to give up their land for $7,500 in the 1836 Platte Purchase. Congress approved this land deal in 1837. Southern Congressmen supported it because it added land to the only slave state north of Missouri's southern border. An area almost as big as Rhode Island and Delaware combined was added to Missouri. It included Andrew, Atchison, Buchanan, Holt, Nodaway, and Platte counties.

Trade and Travel in Early Missouri

Many Southerners moved into Missouri Territory between 1804 and 1821. The population grew fast because treaties removed Native American land claims. Settlers were drawn by cheap, good land and easy access by the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. By 1810, European Americans were the main group. They outnumbered the French-speaking people and pushed Native Americans further west. Public land was quickly surveyed and sold to yeoman farmers. Their hard work paid off quickly. Ranchers raised cattle. Missouri's woodlands had plenty of grass for grazing. New settlers built the foundation for the new state. Their influence is still strong today.

The best farming lands were along the Missouri River. Wealthy farmers, often slaveowners from Kentucky and Tennessee, moved there. They planned to grow crops for sale, using the excellent river transport system. As historian Douglas Hurt noted, owning land meant more than just money. It provided security, showed independence, and gave farmers control over their families and slaves.

St. Louis was the main city in the northern territory. It was located where major northern and western rivers met. It had merchants who could equip expeditions. It was also a place for information and experienced travelers. After Lewis and Clark went west, Zebulon Pike explored the northern Mississippi River in 1805. In 1806, Pike led another trip to the southern and western parts of the Arkansas River. The Pike Expedition of 1806 spent the winter in Colorado mountains. Then they went into Spanish territory and were held prisoner until 1808. Another important trip from St. Louis was by Stephen Harriman Long. He traveled up the Platte River in 1820 and called the Great Plains the "Great Desert."

Steamboats started navigating the Mississippi-Ohio river systems in 1811. The New Orleans steamboat traveled from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to New Orleans. On December 16, 1811, the New Madrid earthquakes hit the area. In 1817, the first steamboat reached Saint Louis. In 1820, steamboats made the trip from New Orleans to Louisville in 15 to 20 days. By 1838, it took 6 days or less. By 1834, there were 230 steamboats on the Mississippi. Many flat boats also carried goods downstream. In 1842, Ohio finished a canal system connecting the Mississippi with the Great Lakes. These were connected to the Hudson River and New York City by the Erie Canal in 1825. Trade of goods and farm products grew greatly on the rivers and Great Lakes.

The population of the Mississippi River region served by St. Louis grew fast to about 4 million people by 1860. Railroads were just starting to be important in the late 1850s. Riverboat traffic ruled transportation and trade. St. Louis thrived at the center. It had connections east along the Ohio, Illinois, Cumberland, and Tennessee rivers. It connected west along the Missouri River, and north and south along the Mississippi.

In 1845, St. Louis was connected by telegraph to the east coast. That same year, the first banks and colleges west of the Mississippi were started. Business leaders in St. Louis were mostly from the East, with some Southerners. Many workers, especially skilled ones, were German immigrants. Politicians were Southerners and Irish Catholic immigrants.

After the California Gold Rush began in 1848, Saint Louis, Independence, Westport, and especially Saint Joseph became starting points for people going west. They bought supplies in these cities for the six-month trip to California. This earned Missouri the nickname "Gateway to the West." The Gateway Arch in St. Louis remembers this.

In 1848, Kansas City was officially formed on the Missouri River. In 1860, the Pony Express started its short run carrying mail from Saint Joseph to Sacramento, California.

In the 1820s, many farmers moved to northeastern Missouri, especially from the Bluegrass region of Kentucky. They brought a farming style from the upper South. It mixed hog and corn production by small farmers with cattle and tobacco production by large farmers. Families often moved together in large groups. They bought land close to each other.

Missouri was famous for its high-quality mules. The state produced a superior breed from Mexican and Eastern animals. Some were used on western trails. More were used on southern plantations. The mule industry provided full-time jobs for some traders and breeders. But it also helped many farmers earn extra money. Horses were bigger and cost more to keep, but they could do more work. They remained the favorite animal on Missouri farms.

Religion and Community Life

After Louisiana became part of the United States, government support for the Catholic Church ended. Rules against Protestant groups were also removed. Without money from the state, most priests left. Catholic church members had no leader from 1804 to 1818. A Catholic school, St. Louis Academy (later Saint Louis University), was started in 1818. It was the first college west of the Mississippi River.

When Louis William Valentine Dubourg became the Catholic bishop in 1818, Catholicism grew again. New religious orders like the Society of the Sacred Heart and the Society of Jesus formed. Within months, DuBourg started building a new cathedral in St. Louis, now called the Basilica of St. Louis, King of France. DuBourg also encouraged schools for white settlers and Native Americans. The Academy of the Sacred Heart in St. Charles was started by Rose Philippine Duchesne in 1818. DuBourg also helped set up many churches across Missouri. DuBourg's successor, Joseph Rosati, continued to support the Catholic church. In 1828, the Sisters of Charity opened the first hospital in Missouri. In 1838, the Sisters of St. Joseph opened the first asylum for the deaf at Carondelet.

More immigrants from Ireland and Germany helped the Catholic church grow after Missouri became a state. In the 1830s, Catholic German communities settled in Cole, Gasconade, Maries, and Osage counties.

During the territorial period, Protestant churches grew quickly because preaching rules were lifted. Baptist, Presbyterian, and Methodist ministers arrived. They held outdoor services in the summer and started churches for regular worship. Most early Protestant churches were in rural Missouri. The first Baptist church was started in 1805 near Cape Girardeau. The first Methodist church was started near Jackson in 1806. The first Presbyterian church was started ten miles south of Potosi in 1816. The first Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) was started in Howard County in 1817. The only Protestant church not started in rural Missouri was the Episcopalian Church. It started its first church in St. Louis in 1819.

The early Baptist church in Missouri was started by John Mason Peck and James E. Welch. They were sent by the Baptist Board of Foreign Missions. They started churches in rural Missouri. They also founded the first Sunday school in St. Louis for white children and another for black children in 1818. The black Sunday school grew fast. This led to the first black Baptist church in Missouri in 1827. The Baptist church continued to grow until the Civil War. In 1834, there were 150 Baptist churches. By 1860, there were 750.

The first Methodist church was started in 1806 near Jackson. But a formal church building was not built until 1819. This church, called McKendree Chapel, was named for the first Methodist elder in the territory. It is the oldest Protestant church still standing in the state. Much of the Methodist growth came from their use of camp meetings. In these meetings, travelers and locals set up tents around an outdoor seating area. Services were known for strong emotions and passionate preaching.

Presbyterians and Congregationalists worked together in Missouri until 1852. They started churches for both white settlers and Native Americans in the western part of the state. Neither group grew as fast as the Methodists and Baptists. But they still helped with education and culture in the state. Salmon Giddings was called the "founder and father of Presbyterianism" in Missouri. He started twelve churches, including the first Protestant church in St. Louis. The first completely separate Congregationalist church was started by a former Presbyterian group in St. Louis in 1852.

Other churches formed around the time Missouri became a state. These included the Episcopal church (1819), the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (1830), Lutherans (1830s), and a Jewish group (1836). The first Episcopal church struggled after its leader left in 1821. It didn't grow again until Thomas Horrel arrived in 1825. Under Horrel, the group built a brick church in 1830. In 1844, the Episcopal Diocese of Missouri separated from Indiana. Cicero Hawks became the first bishop of Missouri. An Episcopal cathedral in St. Louis was built during his time.

Two groups of Lutherans came to Missouri in the 1830s because of German immigration. The first group formed the Evangelical Synod of North America in 1840. In 1849, the Synod opened a seminary (a school for religious leaders) called Eden Seminary. It later moved to Webster Groves. A second group of Lutherans came in 1839. They were mostly from Saxony and settled in Perry County. They were led by Martin Stephan and later by Carl Walther. This group eventually formed the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod.

Mormon Settlements and Conflicts

The first "Mormons" (members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) arrived in 1830 near Independence, Missouri. Joseph Smith, the church leader, and his followers moved to Independence in 1831. Smith said that God told him the area around Independence would become Zion, a gathering place. By 1833, one-third of the people in Jackson County were Mormons, about 1,200 followers.

Within two years, neighbors in Independence became very unfriendly. This was partly because Mormons bought large amounts of land. They openly said they planned to control the area, which made non-Mormons suspicious. Mormons also voted together and mostly traded among themselves. They also supported ending slavery. In July 1833, non-Mormons met in Independence to talk about their complaints. They agreed that all Mormons were banned from the county. When Mormons refused, mobs attacked their local newspaper and two Mormon leaders, Edward Partridge and Charles Allen, were tarred and feathered.

At first, the Mormons agreed to leave quickly. But after Missouri Governor Daniel Dunklin promised protection, Mormons brought more settlers and broke their agreement. Angry anti-Mormon groups attacked the Mormon community again in October 1833. When state courts and the militia didn't help, most Mormons left Independence by early 1834. For the next three years, most Mormons lived in nearby Clay County. But in 1836, local people again demanded Mormons leave. This time, Mormon leaders arranged for the state to create Caldwell County to the north as a Mormon safe place. There, Mormons built the town of Far West. Far West and Caldwell County quickly became a place for Mormon settlers.

In 1838, fighting broke out again between Mormons and non-Mormons. This was called the 1838 Mormon War. It started from an election dispute where non-Mormons tried to stop Mormons from voting. Open fighting began, and many people, including civilians, were killed. Missouri Governor Lilburn Boggs sent a state militia to attack the Mormons. He issued Missouri Executive Order 44, which said:

The Mormons must be treated as enemies and must be exterminated or driven from the state if necessary for public peace.

—Governor Lilburn Boggs

After learning the state militia was involved, the Mormon forces gave up. Many Mormon religious leaders, including Joseph Smith, were jailed. After several trials, Smith and the other leaders were allowed to escape. He and his church moved to Illinois to form the city of Nauvoo in 1839. The way Mormons were treated in Missouri was very unfair. Historian Duane G. Meyer called it "one of the sorriest episodes in the history of the state." Despite this, Missouri still has many places important to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Schools and Newspapers

The small French towns that became part of the United States in 1803 had limited schooling. Schools were started in several Missouri towns. By 1821, they were in St. Louis, St. Charles, Ste. Genevieve, Florissant, Cape Girardeau, Franklin, Potosi, Jackson, and Herculaneum. There were also schools in rural Cooper and Howard counties. These were private schools run by traveling teachers. They taught boys from families who could pay small fees and provide room and board for the teacher. A few schools for both boys and girls existed in some rural areas by the 1830s. Eleven schools for girls also operated during the territorial period. But these focused on basic reading and writing and homemaking skills.

In the decades after Missouri became a state, newspaper and book publishing grew fast. From 1820 to 1860, the number of newspapers in the state grew from 5 to 148. The biggest growth was in the 1850s. But early newspapers were slow to get news. This problem was solved when the telegraph arrived in 1847. Newspapers often included long lessons, poetry, stories, and articles from other papers. After 1847, newspapers could provide news from across the country within one day.

After 1825, most Missouri newspapers openly supported or opposed President Andrew Jackson. Two important newspapers were the Missouri Statesman in Columbia and the Missouri Democrat in St. Louis. The Statesman was a strong political force in central Missouri. It supported the Whig Party. The Democrat supported Jacksonian Democrats until the 1850s. Then it switched to support the new Republican Party. Democratic papers supported Thomas Hart Benton. These included the St. Louis Union and the Jefferson City Enquirer. The Hannibal Journal employed Samuel Clemens as a typesetter. The St. Louis Observer was the newspaper of Elijah Parish Lovejoy, an early opponent of slavery.

A few newspapers, mostly in St. Louis, were printed in German or French. One of the earliest was the Anzeiger des Westens, a German paper started in 1835 that supported Benton's politics. Other important German papers included the Westliche Post (St. Louis, 1857) and the Hermann Volksblatt (1854). The French paper La Revue de l'Ouest started in St. Louis in 1854.

Literature in Missouri often included non-fiction travel stories and biographies. It also had collections of short stories about life on the frontier. Thomas Hart Benton's biography of his thirty years in government was popular. Henry Boernstein's The Mysteries of St. Louis was reviewed in local papers.

Slavery and "Bleeding Kansas"

After the Louisiana Purchase, the number of enslaved black people in Missouri grew a lot. This was especially true in the 1820s and 1830s. The highest percentage of slaves in the state was 18 percent in 1830. By 1860, it was 9.8 percent. This was because many Irish and German immigrants arrived from the 1840s, and more people moved from the eastern United States. In St. Louis, 9 percent of the 14,000 people in 1840 were slaves. By 1860, only 1 percent of the 57,000 people were enslaved. Few Missouri families owned slaves. But many white people from the South did not oppose slavery. They thought freeing slaves would be bad for white people. Before 1830, slaves in Missouri cost less than $500. But as the state's population grew, so did demand. By the 1850s, field slaves often sold for over $1,000 each.

| Black slave population of Missouri | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1810 | 3,011 | — |

| 1820 | 10,222 | +239.5% |

| 1830 | 25,091 | +145.5% |

| 1840 | 57,891 | +130.7% |

| 1850 | 87,422 | +51.0% |

| 1860 | 114,931 | +31.5% |

In most of the state, slavery was not very profitable and not widely practiced. The enslaved population was mostly in areas along the Missouri and Mississippi rivers. Even so, slavery was a big part of Missouri society. Slave labor was very important to the state's growth. Rich planters from Kentucky and Tennessee moved to the Little Dixie region in central Missouri. They bought large areas of fertile land and brought slaves to grow hemp and tobacco.

Missouri's laws about slavery, like those in many other slave states, treated slaves as property that could be bought and sold. The Missouri Constitution of 1820 said that the government should make laws to ensure slaves were treated humanely. In 1825, the government adopted a slave code. But most slaves had no legal protection. Later laws included one in 1847 that banned teaching slaves to read or write. It also banned free black people from moving to the state. Other rules said slaves could not buy or sell property without their owner's permission. They could not buy or sell alcohol. Slave marriages were not legally recognized. Slaves also could not be witnesses against white people. They could not hold meetings, including church services, without permission and a white person present. The Missouri government also made laws to fight against people who wanted to end slavery or slave rebellions. In 1837, making slaves rebel was punishable by fine and other penalties. Also in 1837, patrols were set up to watch slave activities. In 1843, illegally taking a slave out of the state was made a serious crime.

Despite the harshness of slavery, some slave owners in Missouri showed real concern for their slaves. This was often because of the way slavery worked in Missouri. Owners directly oversaw their slaves, worked alongside them, and lived in the same or nearby houses. For example, William Jewell was buried next to his slaves. Other masters freed their slaves, including Ulysses S. Grant. Owners sometimes said this made slavery milder. Some slaves, who feared being sold further south, agreed. Historian Mutti Burke studied slaves on farms and in towns along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. She looked at the economics of slavery, relationships between slaves and owners, challenges for slave families, and how slavery ended during the Civil War.

Like many slave states, Missouri had a small population of free black people. By the mid-1800s, this group grew because some slave owners freed their slaves. Free black people had some protections. In 1824, the Supreme Court of Missouri ruled that free black people could not be re-enslaved. But this rule was not always followed. Free black people were still in danger of being enslaved by dishonest traders. In 1846, a court case started that would decide the rights of free black people and slaves: Dred Scott v. Sandford. Dred and Harriet Scott, who were slaves, sued for their freedom in St. Louis. They argued they had lived in a free state and territory. The case went on until 1857. It ended with a major U.S. Supreme Court decision. Chief Justice Roger Taney and five other justices denied Scott his freedom. They also said that no black people were citizens. They said Congress had no power to stop slavery in the territories. This decision overturned the Missouri Compromise of 1820. It basically stopped Congress from preventing slavery from spreading in the United States.

Critics of slavery in Missouri focused on two things: families being separated and the slave trade. The main slave market in St. Louis was at the courthouse doors. Many people at the time wrote about families being separated there. One St. Louis resident wrote that a woman often bought baby slaves from their mothers to raise and sell later for profit. By the mid-1850s, some Missouri slave owners sold extra slaves to cotton-growing states like Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Texas.

People who openly opposed slavery were a small group in Missouri before the Civil War. Two main groups spoke out against slavery: New Englanders (especially ministers, journalists, and politicians) and German Americans. They were usually based in or near St. Louis. One opponent was John Clark, an anti-slavery Methodist preacher who lived in Missouri. Others, like Presbyterian minister David Nelson, were forced to leave the state in 1836 for speaking against slavery. Elijah Parish Lovejoy, a Presbyterian minister and newspaper editor, had to leave after criticizing a judge and a mob in April 1836. George S. Park, who founded Parkville, Missouri, published his anti-slavery views in the local Parkville Luminary in 1855. In response, a mob raided his newspaper office and destroyed his presses.

Missouri politicians who opposed slavery were careful to avoid problems. In the late 1820s, a meeting was held in Missouri. Both Senator Thomas Hart Benton and Senator David Barton attended. They were supposed to create a plan to free slaves in the state. But the plan was quickly dropped after an incident in New York caused racial tensions. It wasn't until the 1850s that anti-slavery policy was openly discussed by political leaders in the state again. These politicians were connected to Benton. But they went further than he did. They wanted to end slavery, not just stop its spread. These included St. Louisans B. Gratz Brown, Henry Boernstein, and Frank Blair. They represented the liberal German population of their city.

The Underground Railroad, a secret network to help slaves escape to freedom, operated in Missouri in the 1840s and 1850s. Early escape routes from Missouri led to Cairo, Galesburg, Godfrey, Quincy, and Sparta in Illinois. Also to Cincinnati, Tabor, and Grinnell in Iowa. And to Fort Scott and Ossawatomie in Kansas. One successful attempt to free slaves was by John Brown in December 1858. While living at the Osage Settlement, Brown was asked by a slave to help free his family. The next night, Brown led a raid into Vernon County, Missouri. He freed eleven slaves and led them to Canada. Another raid was by John Doy, a Kansas doctor, in Buchanan County, Missouri in July 1859. Doy successfully freed some slaves, but his group was caught. He was jailed at St. Joseph. A group of Kansans, including Silas Soule, broke into the jail and freed Doy before he started his prison sentence. It's hard to say exactly how successful the Underground Railroad was in Missouri. But frequent complaints about people helping runaways show it happened often.

In 1854, Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas suggested a bill to organize the Kansas and Nebraska territories. It would let the people there decide if they wanted slavery through popular sovereignty (meaning the people would vote). This bill, called the Kansas–Nebraska Act, passed and was signed by Franklin Pierce on May 30. Most Missouri Democrats and Whigs supported the bill, except for Thomas Hart Benton and a few of his friends. Several Missouri politicians, including Senator David Rice Atchison and former Attorney General B.F. Stringfellow, encouraged Missourians to settle in the new lands in 1854. They wanted to stop anti-slavery settlers from New England. As early as June 1854, pro-slavery groups suggested that only armed resistance would stop anti-slavery forces from taking over Kansas.

The governor of Kansas said only Kansas residents could vote. But about 1,700 Missourians crossed the border in November 1854 to vote in the Congressional election. Only 2,800 votes were cast. It's likely the pro-slavery candidate would have won without the Missourians' illegal votes. In the March 1855 election for the territorial legislature, over 4,000 Missourians entered Kansas to vote. Even the University of Missouri sent a student to vote for slavery. According to the polls, 6,307 people voted, even though Kansas only had 2,095 eligible voters at the time.

By 1855, anti-slavery immigrants started arriving in Kansas in large numbers. They refused to accept the illegally elected pro-slavery government. The anti-slavery groups elected their own government, with its capital at Topeka by December 1855. But the pro-slavery government at Lecompton remained the legally recognized government. Missourians, led by Senator Atchison, formed armed groups to keep Kansas a slave state. These groups, known as Border Ruffians, started stopping steamboats going through Missouri to Kansas. They searched them and took any weapons they found. In December 1855, a group of Missourians from Clay County took weapons from the federal arsenal at Liberty, Missouri. Federal officials got most of the weapons back, but no one was arrested.

From 1855 to 1856, tensions turned into open warfare along the border. By 1857, many anti-slavery settlers had arrived in Kansas. Their votes outnumbered those of the pro-slavery Missourians who crossed the border for the October election. Even with the anti-slavery victory, violence continued along the Missouri-Kansas border. In some cases, anti-slavery groups from Kansas, known as Jayhawkers, invaded Missouri. They attacked pro-slavery settlements in Bates, Barton, Cass, and Vernon counties. Attacks continued on both sides even after the Civil War.

Civil War and Reconstruction: 1861–1874

By 1860, the population of the Mississippi River region served by St. Louis grew quickly to about 4 million people. Railroads were just starting to be important in the late 1850s. Riverboat traffic dominated transportation and trade. St. Louis thrived at the center, with connections east, west, north, and south.

Elections and the Camp Jackson Incident

From 1852, Missouri's political parties and government changed a lot. In the 1852 governor's election, Democrat Sterling Price won. He was a slaveowner and a veteran of the Mexican–American War. Price strongly supported pro-slavery Missourians in Kansas. He served as governor until 1857. During his term, the Whig Party fell apart. In the 1856 election, Trusten Polk won as the leader of a group of Democrats against Benton. But Polk resigned after only a month to become a senator. In the special election that followed, Benton Democrats and former Whigs supported James S. Rollins. But he lost to another anti-Benton Democrat, Robert M. Stewart. Stewart's time as governor was quiet. His government emphasized both the Union and slavery. He was most known for saving the state's new railroad system from financial trouble.

In April 1860, Claiborne Fox Jackson became the Democratic Party's choice for Missouri governor. In mid-1860, Jackson officially supported Northern Democrat Stephen A. Douglas for president. But he personally favored Southern Democrat John C. Breckinridge. Because of his choice, Southern Democrats nominated their own candidates for governor. Besides the Breckinridge Southern Democrats, Jackson also faced the new Republican Party. This party had strong support among Germans in St. Louis. But Jackson's main opponent was the Constitutional Union Party candidate Sample Orr. In the August 1860 election, Jackson won by a large margin.

Leading up to the November presidential election, Jackson continued to support Stephen Douglas. But he didn't campaign for him in Missouri. Douglas won the state in the 1860 presidential election by only 429 votes over John Bell. In early December, most of Missouri's banks stopped paying in gold or silver. This was because of the political uncertainty after South Carolina left the Union. This economic trouble caused high unemployment in St. Louis and a lack of money in the area. In his January 1861 speech, Governor Jackson blamed Northern abolitionists for the crisis. He said he hoped the Union would not force South Carolina to stay. He asked for a meeting to decide Missouri's future and to discuss leaving the Union. He immediately called up the state militia. His lieutenant governor, Thomas Caute Reynolds, started organizing the militia for possible secession. He led a meeting the day after the inauguration. They decided that St. Louis was key to controlling the state. And controlling St. Louis meant controlling its federal arsenal.

The secessionists' main rivals in St. Louis were Frank P. Blair, a congressman, and Oliver D. Filley, the city's mayor. After Lincoln's election, Blair started organizing Republican groups, mostly anti-slavery Germans, into Home Guard military units. To fight these units, Reynolds convinced the legislature to create a state-appointed board to control the St. Louis Police Department. This put the police under state control. Jackson made the first appointments to the board in late March. Meanwhile, Reynolds went to St. Louis to recruit a secessionist military unit called the Minute Men. The local militia commander talked with the arsenal commander, William H. Bell. Bell promised to turn the arsenal over to the state forces.

When elections were held for representatives to the state convention, voters mostly chose people who supported the Union. No one who openly called for secession was elected. Four openly Republican men were elected from St. Louis. Two reasons for this were the small number of slaveholders in Missouri and the large number of immigrants from the North and other countries. Economically, the state was tied to the North through trade. The South offered little economic or military security.

When the convention met in March 1861, they chose Hamilton R. Gamble, a retired lawyer, to write their report. The report approved of the Crittenden Compromise (even though Congress had rejected it). It also approved of a national meeting to save slavery. It suggested the federal government remove its forces from states that had left the Union to avoid fighting. The convention decided not to recommend that Missouri join the Confederacy if the North rejected compromise or if other border states left the Union.

When fighting started at Fort Sumter, President Lincoln asked for 75,000 volunteers from the states. But Governor Jackson flatly refused Lincoln's request for 4,000 troops from Missouri. To meet the quota, Frank Blair offered the Home Guards. The federal government accepted. The federal government then removed U.S. Army commander William S. Harney. Blair thought Harney was too slow to react. Nathaniel Lyon, who agreed more with Blair, was appointed in February 1861.

Within weeks, Lyon sent extra weapons from the arsenal to safer places in Illinois. He gathered another ten thousand soldiers to defend the state. The state militia, controlled by Jackson and the secessionists, started training after the legislature approved it on May 2. The militia commander asked for artillery from the Confederate government and Virginia. Both agreed and secretly sent aid up the Mississippi River. To find out how strong the camp was, Lyon went in disguise. He saw small Confederate flags and references to Jefferson Davis. He decided to clear the camp using federal troops from the arsenal.

This became known as the Camp Jackson Affair. Union forces marched to the militia camp (named for Governor Jackson). They surrounded it and took the militia prisoners without a fight. As soldiers took the prisoners back to the arsenal, a civilian fired a pistol. This made the soldiers shoot into the crowds watching. In the chaos, 28 civilians were killed and dozens were hurt. After the shooting, many Missourians who had been undecided took a firm side. For Union supporters in rural Missouri, this often meant a difficult situation because there were few Union forces in their area.

Early Battles and Guerrilla Warfare

After Camp Jackson, the General Assembly felt pressured to act against the Union. It quickly passed laws to enroll all able men into the state militia and give it money. Meanwhile, General Harney returned to St. Louis. He had been captured by rebel forces in Virginia. He was released after refusing to join them. He then convinced the War Department that he would keep Missouri in the Union. When he returned, he approved Lyon's capture of Camp Jackson. Then he got warrants to search for and seize illegal weapons. He also sent forces to nearby Potosi to secure its lead supply and the railroad to St. Louis.

Jackson continued to reorganize and train the state militia in mid-1861. It was now called the Missouri State Guard. Jackson named Sterling Price as its commander. Price began organizing thousands of new recruits. In response, Union supporters asked Lincoln to keep Harney as commander of Union forces in Missouri. Others, especially allies of Frank Blair, wanted a more aggressive approach. They pushed for Lyon to replace Harney. Lincoln decided to remove Harney only after several weeks. He wanted to give Harney a chance to finish his moderate goals. But he eventually let Blair remove Harney and appoint Lyon as the new Union commander whenever Blair thought best.

Blair got this permission on May 20. That same day, Harney made an agreement with Sterling Price about troop movements in Missouri. Price would keep his militia out of Greater St. Louis. Harney would not move troops into rural Missouri. Price also sent most of the militia forces gathered in Jefferson City home, except for some to keep order. Historians disagree on Price's reasons. Some say he tried to slow the Union's progress and wanted Missouri to join the Confederacy. Others say he truly wanted to prevent fighting. Despite the agreement, some pro-Confederate forces stayed in Jefferson City. Confederate flags flew at the Governor's Mansion. Jackson was secretly talking with Confederate agents. Pro-secessionists like Lieutenant Governor Reynolds hated the agreement. Reynolds distrusted Price for the rest of the war.

Union supporters in St. Louis were also upset by the agreement. They heard reports of Unionists being harassed outside the city. Blair, reacting to pressure, delivered the order removing Harney on May 30. Lyon took command. Moderates on both sides still hoped to prevent fighting. They arranged a meeting in St. Louis on June 11. Leaders like Jackson, Price, Blair, and Lyon attended. After hours of arguing about the Union's right to recruit troops in Missouri, Lyon decided the meeting was stuck. Lyon stood up and told Jackson and Price:

Rather than concede to the State of Missouri the right to demand that my Government shall not enlist troops within her limits, or bring troops into the State whenever it pleases, or move its troops at its own will into, our of, or through the State; rather than concede to the State of Missouri for one single instant the right to dictate to my Government in any matter however unimportant, I would see you, and you, and you, and every man, woman and child in the State, dead and buried. This means war.

—Nathaniel Lyon

Jackson and Price quickly went back to Jefferson City. They planned their actions and only stopped to burn bridges at the Gasconade and Osage rivers. Price ordered the state guard to prepare for war again. He decided that Boonville would be easier to defend than Jefferson City. The state government moved there on June 13. By June 15, Lyon captured an empty Jefferson City with 2,000 troops. Lyon left 300 men to hold the capital and chased the Confederate state guard to Boonville.

Price and the main part of the Confederate militia had already moved from Boonville. They heard that Union forces were moving on Lexington, Missouri, which Price thought was very important. Price also got sick. Governor Jackson and a state guard colonel stayed to lead a small militia of 400 men to hold Boonville. Lyon and the main Union force caught up with this part of the state guard. The Union easily defeated the secessionists at the Battle of Boonville. Price gathered the rest of the state guard and retreated to Missouri's southern border.

To chase Price and the state guard, Lyon ordered a St. Louis group led by Franz Sigel to move to southwest Missouri. They tried to stop Price's guard from meeting Confederate General Benjamin McCulloch's army in Arkansas. Sigel moved by train to Rolla, then marched on Springfield. They took Springfield on June 23. Moving west from Springfield, Sigel's forces met Jackson and his retreating army on July 7 at the Battle of Carthage. Outnumbered 4,000 to 1,000, Sigel's Union forces were defeated. They retreated to Springfield to wait for Lyon's reinforcements. The state guard forces under Price camped at Cowskin Prairie, near Granby.

In northwest Missouri, Samuel D. Sturgis led Union troops from Fort Leavenworth to St. Joseph. Then they headed south to Lexington to chase Price. In northeastern Missouri, Union forces from Iowa moved on Hannibal. They secured the railroad connecting Hannibal to St. Joseph. This secured northern Missouri for the Union.

Most St. Louis business leaders supported the Union. They rejected efforts by Confederate supporters to take control of the St. Louis Chamber of Commerce in January 1862. Federal authorities stepped in. The conflict split the Chamber of Commerce into two groups. The pro-Unionists finally gained control. St. Louis became a major supply base for Union forces in the entire Mississippi Valley.

Soon after, the 12,000-man force of the Missouri State Guard, Arkansas State Guard, and Confederate regulars defeated the Federal army of Nathaniel Lyon at Wilson's Creek (also called "Oak Hills").

After their success at Wilson's Creek, Southern forces moved north. They captured the 3,500-strong army at the First Battle of Lexington. Federal forces then planned to retake Missouri. This caused the Southern forces to retreat from the state and head for Arkansas and later Mississippi.

In Arkansas, the Missourians fought at the Battle of Pea Ridge and were defeated. In Mississippi, parts of the Missouri State Guard fought at Corinth and Battle of Iuka. They suffered heavy losses.

Political Changes During the War

In 1861, Union General John C. Frémont declared that slaves owned by those fighting against the Union were free. Lincoln immediately reversed this action because it was not authorized. Secessionists tried to form their own state government. They joined the Confederacy and set up a Confederate government in exile. It was first in Neosho, Missouri, and later in Texas. By the end of the war, Missouri had provided 110,000 troops for the Union Army and 40,000 troops for the Confederate Army.

During the Civil War, Charles D. Drake, a former Democrat, became a strong opponent of slavery. He was a leader of the Radical Republicans. From 1861 to 1863, he suggested freeing slaves immediately and without payment. But he was defeated by conservative Republicans led by Governor Hamilton Gamble and supported by President Abraham Lincoln. By 1863, Drake had built up his Radical group. He called for immediate freedom for slaves, a new constitution, and taking away voting rights from all Confederate supporters in Missouri.

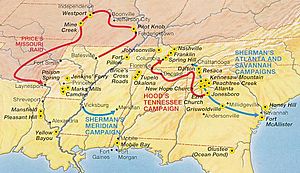

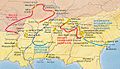

Later Battles and Guerrilla Warfare

In 1864, Sterling Price planned to attack Missouri. He launched his 1864 raid on the state. Price attacked in southeastern Missouri and moved north. He tried to capture Fort Davidson but failed. Next, Price wanted to attack St. Louis, but it was too well-defended. He then moved west, parallel to the Missouri River. Federal forces tried to slow Price's advance with small and large fights, like at Glasgow and Lexington. Price reached the far western part of the state. He fought in a series of tough battles at the Little Blue, Independence, and battle of Byram's Ford. His Missouri campaign ended at the battle of Westport. Over 30,000 troops fought there, leading to the defeat of the Southern army. The Missourians retreated through Kansas and Oklahoma into Arkansas. They stayed there for the rest of the war. In 1865, Missouri ended slavery. It did so before the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was adopted. Missouri adopted a new constitution. It denied voting rights and banned certain jobs for former Confederate supporters.

Besides organized military conflict, Missouri suffered from guerrilla warfare. In such a divided state, neighbors often used the war as an excuse to settle personal disagreements. They took up arms against each other. Roaming groups like Quantrill's Raiders and the men of Bloody Bill Anderson terrorized the countryside. They attacked both military bases and civilian towns. Because of this widespread guerrilla fighting, and support from citizens in border counties, Federal leaders issued General Order No. 11 in 1863. This order evacuated areas of Jackson, Cass, and Bates counties. They forced residents out to reduce support for the guerrillas. Union cavalry could then track down Confederate guerrillas. They no longer had places to hide or people to support them. The army forced almost 20,000 people, mostly women, children, and the elderly, to leave their homes quickly. Many never returned. The affected counties were economically ruined for years after the war. Families passed down stories of their difficult experiences for generations.

Western Missouri was a scene of brutal guerrilla warfare during the Civil War. Some raiding units became organized criminal gangs after the war. In 1882, the bank robber and former Confederate guerrilla Jesse James was killed in Saint Joseph. Vigilante groups appeared in remote areas where law enforcement was weak. They dealt with the lawlessness left over from the guerrilla warfare. For example, the Bald Knobbers were vigilante groups in the Ozarks. In some cases, they also turned to illegal gang activity.

Helping Soldiers and Reconstruction

The Western Sanitary Commission was a private group in St. Louis. It was a rival to the larger U.S. Sanitary Commission. It worked during the war to help the U.S. Army with sick and wounded soldiers. It was led by people who wanted to end slavery. After the war, it focused more on the needs of freed slaves. It was founded in August 1861 by Reverend William Greenleaf Eliot. It cared for wounded soldiers after the first battles. It was supported by private donations in St. Louis, California, and New England. It selected nurses, provided hospital supplies, set up hospitals, and equipped hospital ships. It also provided clothes and places to stay for freed slaves and refugees. It set up schools for black children. It continued to fund charity projects until 1886.

Radical Republicans and New Laws

In November 1864, national and statewide elections gave the Radical Republicans strong majorities. In the General Assembly, most new representatives were relatively young farmers. 56 percent of Radicals were under 45, and 36 percent worked in agriculture. In congressional elections, all but one winner was a Republican. Voters approved a plan for a state convention to rewrite the state constitution. Anyone who had given any indirect support to the Confederacy lost their vote and the right to hold office or practice a profession.

Drake served as vice president of the 1865 state constitutional convention. He was the most active leader. Republican leader Carl Schurz said about him, "in politics he was unyielding." Most members of his party, especially in rural areas, were afraid of him. The state convention began on January 7, 1865, in St. Louis. Like the General Assembly, it was dominated by young Radical Republicans. One of the first things they did was pass an emancipation law on January 11. It took effect immediately. It freed all slaves in Missouri, without paying their owners.

The new Constitution was adopted and became known as the "Drake constitution." The Radicals had complete control of the state from 1865 to 1871, with Drake as their leader. The new government replaced hundreds of local elected officials. They appointed their own people to control local affairs. The Radicals took away voting rights from every man who had supported the Confederacy, even indirectly. They made a long list of 81 actions that could cause someone to lose their rights. They also required an Ironclad Oath for all professional men and government officeholders. This became a very controversial political issue and split the Republican party. German Republicans were especially angry. Historians have pointed out that the Radicals wanted power, revenge, and equal rights for black people. The Radicals had another goal: to use the loss of rights for former Confederates to encourage them to leave Missouri. They also wanted to discourage Southern whites from moving to Missouri. The idea was that Missouri would attract Northerners and European immigrants. This would lead to economic growth and social progress. In 1867, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the federal ironclad oath for lawyers and the similar Missouri state oath for ministers, lawyers, teachers, and other professionals were unconstitutional. This was because they violated rules against bills of attainder and ex post facto laws. To get more votes, the Radicals wanted all black men in Missouri to vote. In a statewide vote in 1868, Democrats were strongly against it. Republicans split their vote. Black suffrage (the right to vote) was defeated, with 55,000 in favor and 74,000 against. Black people in Missouri finally got the right to vote in 1870 with the passage of the 15th Amendment. Meanwhile, the Radical group lost support in Missouri to the Liberal Republicans led by Senator Carl Schurz and Governor Benjamin Gratz Brown.

Return to Traditional Politics

Radical rule upset many groups, making the Republican Party weaker. One important group was German Americans. They had voted 80 percent for Lincoln in 1860 and strongly supported the war. They were a strong part of the Republican Party in St. Louis and other immigrant areas. German Americans were angry about a proposed state constitution that discriminated against Catholics and freethinkers. The requirement of a special loyalty oath for priests and ministers was also a problem. Despite their strong opposition, the constitution was approved in 1865. Racial tensions with black people started to appear, especially over competition for unskilled jobs. German communities were worried about black suffrage in 1868. They feared black people would support strict laws, especially banning beer gardens on Sundays. These tensions caused a large group of Germans to leave the Republican Party in 1872. They supported the Liberal Republican party led by Benjamin Gratz Brown for governor in 1870 and Horace Greeley for president in 1872. This split between the Radical Republicans and the Liberal Republicans was very bad for the party. Most Germans started voting for the Democrats. Also, the nationwide Panic of 1873 was a severe economic downturn. This undermined the Republican promises of prosperity. Violence became much more serious, with many attacks on banks and trains. Farmers started to organize to protect their interests. In August 1874, the Democratic Party nominated Charles Henry Hardin as a compromise candidate for governor. They nominated farmer Norman Jay Colman as candidate for lieutenant governor. He got support from rural areas because he supported Free Silver and wanted to repeal the National Bank Act. The team was elected by a landslide, and the Republican era was almost over.

In May 1875, delegates wrote a conservative constitution to replace the Radical one of 1865. Most delegates were conservative, well-educated, and often had ties to the South. 35 of the 68 delegates had served with the Confederacy or supported it. The leader, Waldo P. Johnson, had been removed from the U.S. Senate in 1862 after joining the Confederacy. The new constitution was a reaction against the radical ideas of the 1860s and 1870s. It encouraged local control and reduced the state's powers. It limited the state and local governments' ability to tax. It also reduced restrictions on churches owning property. It required a two-thirds vote by citizens to allow local government to issue bonds. It restricted state lawmakers from creating laws that would only benefit their local areas. The proposal was put to a popular vote on August 2, 1875. The constitution passed by a large majority.

Growth and Modernization: 1875–1919

Missouri's economy grew steadily from the end of the Civil War to the early 1900s. Railroads took the place of rivers, and trains replaced steamboats. From 817 miles of track in 1860, there were 2,000 miles in 1870 and 8,000 by 1909. Railroads built new towns for repairs and services. Old river towns declined. Kansas City, which didn't have a navigable river, became the rail center of the West. Its population exploded from 4,400 in 1860 to 133,000 by 1890. Cities of all sizes grew. The number of Missourians living in communities over 2,000 people jumped from 17 percent in 1860 to 38 percent in 1900. Coal mining grew rapidly, providing fuel for locomotives, factories, stores, and homes. The lumber industry in the Ozarks also grew, providing wood for railroad ties and bridges. St. Louis remained the top railroad center. It unloaded 21,000 carloads of goods in 1870, 324,000 in 1890, and 710,000 in 1910. The total weight of freight carried on all Missouri railroads doubled and then doubled again, from 20 million tons in 1881 to 130 million in 1904.

Economic Revival and City Growth

The most important economic change in late 19th century Missouri was the growth of railroads. Railroads connected Missouri to the national market. This led to specialized businesses in almost every area. It shifted main traffic away from rivers to East-West rail lines. The first railroads were built in Missouri in the 1850s. But major expansion began in the 1870s. Between 1870 and 1880, Missouri's trackage almost doubled from 2,000 to 3,965 miles.

Railroads also encouraged the growth of surface roads. When the St. Louis–San Francisco Railway arrived in Springfield in 1870, several roads were built nearby. These roads connected a region over 100 miles wide. Another result of railroad expansion was a big increase in the population and wealth of Missouri's cities. In Jefferson City, the area near the Pacific Railroad roundhouse became wealthy. New businesses opened there, like the Dulle Mills, the Jefferson City Gas Works, and the Jefferson City Produce Company. The town of Sedalia was planned because it was close to the Pacific Railroad. The opening of the Missouri–Kansas–Texas Railroad there only made it grow faster.

Among Missouri's rural towns, Joplin grew the most in the late 19th century. This was largely because iron ore was discovered near the town in the early 1870s. A group of Joplin investors created a railroad line in 1877 to help move iron and coal. In 1879, the Joplin and Girard Railroad was sold to the St. Louis—San Francisco Railway. Joplin had no people in 1870. Its population grew to 7,000 in 1880 and 10,000 in 1890. Another example of fast growth from railroads was Cape Girardeau. An early railroad project there failed in 1873 because of an economic crisis. But railroad promoter Louis Houck was hired to restart the company. In late 1880, Houck completed a 14.4-mile stretch connecting Cape Girardeau to the Iron Mountain Railroad. Houck continued to expand the railroad successfully. He eventually built over 500 miles of track in southeast Missouri.

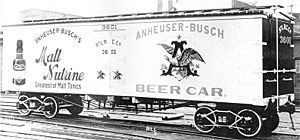

St. Louis and Kansas City grew dramatically after the Civil War. St. Louis especially benefited from better railroad connections after the Eads Bridge was built in 1874 across the Mississippi River. In the 1870s alone, the value of manufactured goods in St. Louis grew from $27 million to $114 million. In the 1880s, it doubled again to $228 million. One of St. Louis's biggest success stories was the Anheuser-Busch brewery. It was founded in the 1860s by Eberhard Anheuser, who partnered with his son-in-law Adolphus Busch. Busch was a pioneer in using pasteurization to keep beer fresh. He sold Anheuser-Busch products nationally using refrigerator cars. He also gave saloons free pictures that advertised the company.

Kansas City also grew fast during this time. Its population increased from 3,500 in 1865 to over 32,000 in 1870. This was largely due to the efforts of Joseph G. McCoy. Kansas City became a center for both meatpacking and wheat milling. Armour & Company became a major employer in the city. Canned beef production in Kansas City was almost 800,000 cans in 1880. It grew to over 4 million cans in 1890. By 1878, the city processed over 9 million bushels of wheat a year. In 1880, eleven railroad lines operated in the city.

Decline of Southern Trade

During the Civil War, the U.S. government closed the Mississippi River to regular trade. This was so military traffic could move faster. After the war, the South's economy was ruined. Hundreds of steamboats were destroyed. Levees (river banks) were damaged by war and floods. Much of the trade from the West that used to go to New Orleans via the Mississippi now went to the East Coast. It traveled via the Great Lakes and the many new railway lines through Chicago. Some river trade on the Mississippi came back after the war. But a sandbar at the mouth of the Southwest Pass in its delta stopped it. Eads' jetties created a new shipping passage in 1879. But the facilities for transferring goods in New Orleans were much worse than those used by railways. Steamboat companies did not do well.

Farming Changes and Growth

Until the 1880s, the six southeastern counties of Missouri's Missouri Bootheel were swampy and often flooded. They were heavily forested, undeveloped, and had few people. Starting in the 1880s, railroads opened up the Bootheel for logging. In 1905, the Little River Drainage District built a complex system of ditches, canals, and levees to drain the swampland. As a result, the population more than tripled from 1880 to 1930. Cotton farming grew a lot. By 1920, cotton was the main crop. This attracted new farmers from Arkansas and Tennessee.

Railroads brought big changes to Missouri agriculture in the late 19th century. They provided outside markets for local crops. They also brought competition from farmers in other parts of the United States. Norman J. Colman, a farmer who worked for the state Board of Agriculture from 1867 to 1903, encouraged Missouri farmers to use scientific farming methods. This would help them compete in the national market. In 1870, Colman convinced the General Assembly to create a College of Agriculture at the University of Missouri in Columbia. This was helped by state lawmaker James S. Rollins. The famous agricultural researcher Jeremiah W. Sanborn became the college's second dean in 1882. In 1883, the college sponsored many agricultural institutes across Missouri. These taught farmers modern practices. Colman continued to support agriculture in Missouri after he was appointed U.S. Commissioner of Agriculture in 1885. In 1888, Colman became the first Secretary of Agriculture when the department became a cabinet-level agency.

Because of the work of Colman, Sanborn, and others, the number of Missouri farms grew significantly in the 1870s. At the start of the decade, the state had just under 150,000 farms and 9.1 million acres of farmland. By 1880, there were over 215,000 farms and 16.7 million acres of farmland. With the arrival of the railroad, some counties and towns grew fast. In 1870, rural Wayne County had no railroad. It had 27,500 acres of farmland and produced 290,000 bushels of corn. In the early 1870s, the town of Piedmont in Wayne County became a railroad junction. Production grew dramatically. By 1880, the county had 47,000 acres of farmland and produced 525,000 bushels of corn. Piedmont itself went from an unmapped village in 1871 to a town of 700 residents by 1880. It had professionals and shops that attracted farmers.

| Year | Number of farms | Acres of farmland (millions) | Rural population (as percent of total) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 148,000 | 9.1 | — |

| 1880 | 215,000 | 16.7 | 74.8 |

| 1890 | 238,000 | 19.8 | 68 |

| 1900 | 285,000 | 22.9 | 67 |

Even with growth from railroads and new methods, Missouri continued to become more urban in the late 19th century. Machines like the sulky plow, corn planter, mower, and reaper made farmers more productive. This meant fewer farm laborers were needed, and many moved to towns. Also, railroad competition generally caused farm prices to drop after 1873. In 1874, a bushel of Missouri corn sold for 67 cents. But its price dropped to 24 cents in 1875 and stayed between 20 and 40 cents for most of the 1870s and 1880s. So, even though farmland increased from 1870 to 1880, the value of crops produced went down from $103 million to just under $96 million in the same period.

In response to falling prices and new scientific methods, farmers started forming chapters of The Grange. Oliver Hudson, a U.S. Bureau of Agriculture employee, formed the first Missouri Grange chapter in 1870. By 1875, Missouri led the nation with over 2,000 chapters. The Grange organized social events for farmers and their wives. It also helped them economically by creating trade fairs and selling farm produce together. The group opened at least eight cooperative stores where Grange members could buy goods at fair prices. Grange stores operated in several market towns.

Despite the Grange's efforts, most Missouri farmers remained economically disadvantaged in the 1880s and 1890s. The number of farms and cultivated land increased again in the 1880s and 1890s. However, about half of the state's claimed land was still not farmed in 1900. In 1903, the state still had over 400,000 acres of unclaimed federal land available under the Homestead Act. By 1900, urbanization had reduced the rural population to two-thirds of the state total. This was down from over 75% at the end of the Civil War. After big declines in the 1880s, land prices recovered slightly in the 1890s. But the market remained unstable and depended on the specific farm. Another factor in farmers' ongoing economic problems was the increasing availability of credit from eastern bankers. High interest rates often led to farms being taken back and sold by the sheriff in the 1890s.

The late 19th century saw no major changes in the types of crops grown in Missouri. Most land was used for corn and wheat. In 1900, farmers used over 7.5 million acres (out of nearly 23 million total) for corn. But overall yields went down as less productive land was used. Most corn in Missouri was eaten by livestock. Hay and pasture land for livestock made up 10.5 million acres of farmland in 1900. Livestock income provided 55% of farm income in 1900, about $142 million.

The largest group of livestock was pigs, totaling 4.5 million in 1900. Cattle were next, with almost 3 million in 1899. Missouri farmers produced 7% of the national total of hogs in 1900. Only Illinois and Iowa had more hogs. Sheep, goats, and turkeys were not very important. But raising chickens was an important extra income for farmers in the 1890s. Like with pigs, Missouri ranked third among poultry-raising states. Missouri mules remained famous nationally. From 1890 to 1900, the number of mules in the state increased from 196,000 to nearly 250,000. During the Boer War from 1899 to 1902, Missouri shipped over 100,000 mules to Britain. The U.S. government bought many mules during the Spanish–American War in 1898 and 1899.

Ozark Farming Changes

Before 1870, the first settlers in the Ozark Mountains were part-time farmers, herders, and hunters. From 1870 to 1900, the region became one of full-time small farms. They grew different crops and raised various animals. Hunting and fishing became hobbies, not just for survival. After 1900, commercial farming increased, and raising livestock became more important than growing crops. The old general farm disappeared. Only dairy farming survived the pressure of livestock production. By the 1970s, farming in the Ozarks had changed again. Many modern farmers could only survive by farming part-time. Most people commute to paid jobs for most of their income, similar to how pioneers had to do many different things to survive.

Women, Families, and Society

In the early 1800s, Missouri had two different family styles: French and American. French families often had the mother as the head of the house. American families often treated the mother as a helper who was less important than the men. Most people who moved to Missouri in the 1800s came as families. Women wrote diaries, letters, and memories about preparing for the journey, the scary Atlantic crossing, and the long train rides from New York City to St. Louis and their final homes. Most came from Germany, as well as Ireland, Bohemia, Hungary, Italy, Poland, and Jewish communities in Eastern Europe. The largest groups were Catholic, Lutheran, and German. Once they arrived, these women—mostly in their twenties—dealt with daily life problems in a new and sometimes unfriendly place. They had limited family nearby to help. The common idea for German American women was to be good, hardworking, obedient, and quiet homemakers. But historical records show more variety. Many women were argumentative, complained, and didn't want to be less important than men. These women who didn't follow the rules had a bigger impact on their communities than if they had strictly conformed.

Modernizing Rural Life

Throughout the century, most rural families lived traditional lives, with men as the main authority. Efforts to modernize rural life and improve women's status were seen in many movements. These included public schools, women's church activities, temperance reform (reducing alcohol use), and the fight for women's right to vote. Reformers wanted to modernize the rural home by changing women from producers (making things) to consumers (buying things). The Missouri Women Farmers' Club (MWFC) was especially active. Most women were full-time homemakers. Their work created materials, clothing, food, and other basic necessities for their families. After the Civil War, some women became wage earners in industrial cities. It was common for widows to run boardinghouses or small shops. Younger women worked in tobacco, shoe, and clothing factories. Some women helped their husbands publish local newspapers, which were common in every county seat and small city. In 1876, women started attending the Missouri Press Association's meetings. By 1896, women formed their own press association. By the end of the century, women were editing or publishing 25 newspapers in Missouri. They were especially active in creating features to entertain their women readers and help women with housework and child-rearing.

Schooling for All