Jimmy Doolittle facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

James Doolittle

|

|

|---|---|

General James Harold Doolittle

|

|

| Born | December 14, 1896 Alameda, California, U.S. |

| Died | September 27, 1993 (aged 96) Pebble Beach, California, U.S. |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/ |

United States Army (1917–1918) United States Army Air Corps (1918–1941) United States Army Air Force (1941–1947) United States Air Force (1947–1959) |

| Years of service | 1917–1959 |

| Rank | General (Honorary) |

| Commands held | Eighth Air Force Fifteenth Air Force Twelfth Air Force |

| Battles/wars | World War I Mexican Border Service World War II

|

| Awards | Medal of Honor Army Distinguished Service Medal (2) Silver Star Distinguished Flying Cross (3) Bronze Star Medal Air Medal (4) Presidential Medal of Freedom |

| Spouse(s) |

Josephine Daniels

(m. 1917; died 1988) |

| Children | 2 |

| Other work | Air race pilot, test pilot, Shell Oil Company VP and director, chairman of Space Technology Laboratories and NACA |

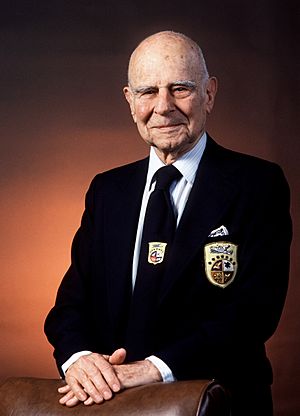

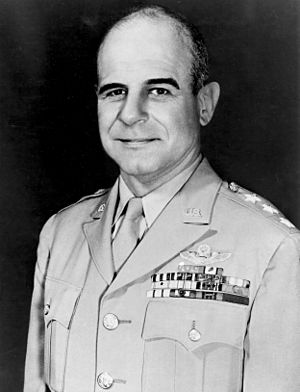

James Harold Doolittle (born December 14, 1896 – died September 27, 1993) was an amazing American general and a true pioneer in aviation. He won the Medal of Honor for a super brave air raid on Japan during World War II. He was also famous for flying across the country, setting speed records, winning air races, and helping create 'instrument flying' – flying only by looking at gauges, not outside.

Jimmy Doolittle grew up in Nome, Alaska. He went to the University of California, Berkeley and later earned a special degree in flying machine science (aeronautics) from Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1925. He was the first person in the U.S. to get such a degree! In 1929, he invented "blind flying," where pilots use only their instruments to fly. This made it possible for planes to fly in bad weather and won him the Harmon Trophy.

He was a flight teacher in World War I and later joined the United States Army Air Corps. During World War II, he was called back to active duty. He led the famous Doolittle Raid on April 18, 1942. This was a daring air attack on Japan, just four months after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Sixteen B-25 Mitchell bombers took part. The raid really boosted American spirits and made Doolittle a national hero.

Doolittle became a lieutenant general and led important air forces in North Africa, the Mediterranean, and Europe. He retired from the Air Force in 1959 but kept working on new technologies. In 1967, he joined the National Aviation Hall of Fame. In 1985, President Ronald Reagan promoted him to a full general. In 2003, Air & Space/Smithsonian magazine called him the greatest pilot ever. He passed away in 1993 at 96 years old and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Jimmy Doolittle was born on December 14, 1896, in Alameda, California. He spent his childhood in Nome, Alaska, where he became known as a good boxer. His parents were Frank Henry Doolittle and Rosa Cerenah Doolittle. By 1910, Jimmy was going to school in Los Angeles.

He saw his first airplane at the 1910 Los Angeles International Air Meet at Dominguez Field. After high school, he went to Los Angeles City College and then the University of California, Berkeley. He studied mining there.

In October 1917, Doolittle joined the Signal Corps Reserve as a flying cadet. He trained at the University of California and Rockwell Field, California. On March 11, 1918, he became a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army.

Military Career and Flying Records

During World War I, Doolittle stayed in the U.S. and worked as a flight instructor. He taught at several airfields across the country. He was a flight leader and gunnery instructor at Rockwell Field. He also patrolled the Mexican border with the 90th Aero Squadron. On July 1, 1920, he became a first lieutenant in the Air Service.

On May 10, 1921, Doolittle helped rescue a plane that had crashed in a Mexican canyon. He flew the plane out himself from a small airstrip they made on the canyon floor. He then went back to college and earned his degree from the University of California, Berkeley in 1922.

Doolittle became one of the most famous pilots between the World Wars. On September 4, 1922, he made a historic flight. He flew a de Havilland DH-4 plane from Florida to California in 21 hours and 19 minutes. This was the first time anyone flew across the U.S. with only one stop! For this, he received the Distinguished Flying Cross.

He then studied aeronautical engineering at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). In 1925, he earned the first doctorate in aeronautical engineering in the U.S. He also won the Schneider Trophy race in 1925, flying a Curtiss R3C at 232 miles per hour. This earned him the Mackay Trophy in 1926.

In 1926, Doolittle broke both his ankles while showing off his flying skills in Chile. Even with casts on, he still performed amazing stunts. After recovering, he became the first person to do an "outside loop" in a plane in 1927. This was a very dangerous maneuver that many thought was impossible.

Pioneering Instrument Flight

Doolittle's biggest contribution to flying was his work on instrument flying. He realized that pilots needed to fly planes without seeing outside the cockpit. This meant relying only on special gauges and instruments. He was the first to understand that pilots' senses could be wrong when flying fast or in bad weather.

He started training pilots to "trust their instruments" instead of what they saw or felt. In 1929, he became the first pilot to take off, fly, and land a plane using only instruments. He helped create and test the artificial horizon and directional gyroscope, which are used by pilots everywhere today. This amazing achievement made it possible for airlines to fly in all kinds of weather.

Working with Shell Oil

In 1930, Doolittle left active military duty and became a Major in the Air Reserve Corps. He also became the manager of the Aviation Department at Shell Oil Company. While there, he helped develop 100-octane aviation gasoline. This special fuel was super important for the powerful planes built in the late 1930s and during World War II.

Doolittle also continued his air racing career. In 1931, he won the first Bendix Trophy race. In 1932, he set a world speed record of 296 miles per hour. He also won the Thompson Trophy race. After winning these three major air racing trophies, he retired from racing. He joked that he had never heard of anyone dying of old age from air racing!

In 1940, Doolittle returned to active duty in the U.S. Army Air Corps. He helped car factories switch to making aircraft for the war effort. He also visited England to learn about other countries' air forces.

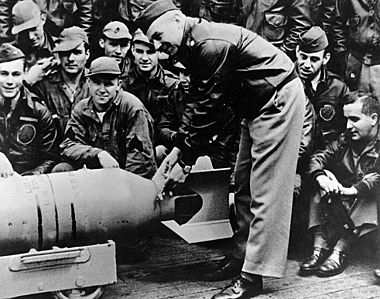

The Doolittle Raid

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Doolittle was promoted to lieutenant colonel in January 1942. He was asked to plan the first air attack on Japan. He bravely volunteered to lead this top-secret mission. The plan was to launch 16 B-25 bombers from the aircraft carrier USS Hornet. Their targets included cities like Tokyo and Kobe.

After training, Doolittle and his crews took off from the Hornet on April 18, 1942. They bombed their targets in Japan. Most of the planes then tried to fly to China, but one landed in Russia. Doolittle and his crew ran out of fuel and had to parachute over China. Chinese helpers and an American missionary named John Birch helped them get to safety. Some other crews were not as lucky, and some airmen were captured or died.

Doolittle thought he would be punished because all the planes were lost. But instead, he received the Medal of Honor from President Franklin D. Roosevelt for his amazing leadership. He was also promoted to brigadier general.

The Doolittle Raid was a huge boost for American morale. It showed Japan that their homeland could be attacked. This made Japan change its war plans, which later led to a big American victory at the Battle of Midway. President Roosevelt famously joked that the raid was launched from "Shangri-La," a fictional paradise.

World War II, After the Raid

In July 1942, Doolittle became a brigadier general. He was assigned to the Eighth Air Force. In September, he became the commanding general of the Twelfth Air Force in North Africa. He was promoted to major general in November 1942. In March 1943, he led a combined force of U.S. and British air units.

From January 1944 to September 1945, he commanded the Eighth Air Force in England. This was his largest command. He was promoted to lieutenant general in March 1944.

New Fighter Tactics

Doolittle made a big change to how fighter planes were used in Europe. Before him, escort fighters had to stay close to the bombers. Doolittle allowed them to fly ahead and attack German fighters. This helped clear the way for the bombers. After bombing their targets, American fighters could then attack German airfields and other targets on their way back. This new tactic was very successful.

Postwar Activities

After Germany surrendered, Doolittle decided not to rush his Eighth Air Force units into fighting Japan. He said he would not risk any planes or crews if the war was almost over.

Doolittle remained active in many areas after the war. In 1951, he became a special assistant to the Air Force Chief of Staff. He helped with missile and space programs. In 1952, President Harry S. Truman asked him to study airport safety. His work led to new rules for buildings near airports and early noise control.

He also became involved in the early days of space science. He had met Robert H. Goddard, who was a rocket pioneer, in the 1930s. Doolittle was concerned about rocket development in the U.S. He later became chairman of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) in 1956. NACA was later replaced by NASA. Doolittle was asked to be the first head of NASA, but he turned it down.

Doolittle retired from the Air Force Reserve in 1959. He returned to Shell Oil as a vice president. In 1947, he became the first president of the Air Force Association. In 1948, he spoke out for ending segregation in the U.S. military. He believed that the military should integrate, just like other industries.

Personal Life

James Doolittle married Josephine "Joe" E. Daniels on December 24, 1917. They were married for exactly 71 years. Josephine Doolittle passed away on December 24, 1988, five years before her husband. She had a special white tablecloth that guests would sign, and she would embroider their names. This tablecloth is now at the Smithsonian Institution.

The Doolittles had two sons, James Jr. and John. Both became military officers and pilots. James Jr. died in 1958 at age 38. His grandson, Colonel James H. Doolittle III, also served in the Air Force.

James H. "Jimmy" Doolittle died from a stroke on September 27, 1993, at the age of 96. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia, next to his wife. At his funeral, a single B-25 Mitchell bomber flew overhead to honor him.

Honors and Awards

On April 4, 1985, President Ronald Reagan promoted Doolittle to the rank of full four-star general on the U.S. Air Force retired list. This was a special honorary promotion.

Besides the Medal of Honor for the Tokyo raid, Doolittle received many other awards. These include the Presidential Medal of Freedom, two Distinguished Service Medals, the Silver Star, three Distinguished Flying Crosses, the Bronze Star Medal, and four Air Medals. He also received awards from countries like Belgium, China, France, and Great Britain. He was the first American to receive both the Medal of Honor and the Medal of Freedom.

In 1972, Doolittle received the Tony Jannus Award for his work in commercial aviation, especially for developing instrument flight. In 1983, he received the Sylvanus Thayer Award from the United States Military Academy. He was also inducted into the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America in 1989 and the Aerospace Walk of Honor in 1990.

Namesakes

Many places are named after Doolittle. These include facilities and streets on U.S. Air Force bases. The headquarters of the Air Force Academy Association of Graduates is called Doolittle Hall. In 2007, the new 12th Air Force operations center at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base was named the "General James H. Doolittle Center."

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: James H. Doolittle para niños

In Spanish: James H. Doolittle para niños