National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics facts for kids

The official seal of NACA, depicting the Wright Flyer and the Wright brothers' first flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina

|

|

Logo

|

|

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | March 3, 1915 |

| Dissolved | October 1, 1958 |

| Superseding agency | |

| Jurisdiction | Federal government of the United States |

The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) was a United States government agency. It was created on March 3, 1915, to study and improve flight. NACA helped make airplanes better and safer.

On October 1, 1958, NACA closed down. Its people and resources were moved to a new agency called the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). NACA is pronounced by saying each letter: N-A-C-A.

NACA made many important discoveries. These include the NACA duct, which helps air flow into engines, and the NACA cowling, which covers aircraft engines. They also created many NACA airfoil shapes, which are still used in airplanes today.

During World War II, NACA was very important for making American planes strong. They helped create special parts called superchargers for high-flying bombers. They also designed the wings for the fast North American Aviation P-51 Mustang. NACA also helped develop the area rule for supersonic aircraft (planes that fly faster than sound). Their research helped the Bell X-1 become the first plane to break the sound barrier.

Contents

How NACA Started

NACA was created on March 3, 1915, during World War I. The government wanted to make sure that scientists, universities, and industries worked together on projects for the war. NACA was inspired by similar groups in Europe, like those in France, Germany, and Britain.

Before NACA, in 1912, President William Howard Taft tried to start a similar group. But Congress did not approve it.

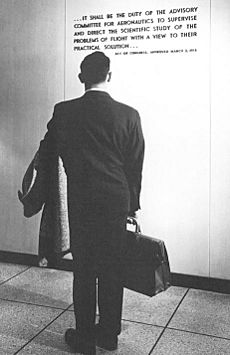

Then, Charles Doolittle Walcott, who led the Smithsonian Institution, tried again in 1915. He suggested creating an advisory committee. Its goal was "to supervise and direct the scientific study of the problems of flight with a view to their practical solution." Even Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt supported the idea. Walcott suggested adding the plan to a bill about Navy money.

The law to create NACA was quietly added to the Naval Appropriations Bill on March 3, 1915. President Woodrow Wilson signed it into law on the same day. The committee had 12 members who were not paid, and they had a budget of $5,000 per year.

NACA's Research and Discoveries

In 1920, Orville Wright, one of the inventors of the airplane, joined NACA's board. By the early 1920s, NACA had a bigger goal: to help both military and civilian aviation by doing advanced research. NACA scientists used their own special tools, like wind tunnels and engine test areas. Other companies and the military could also use NACA's facilities.

NACA's Research Facilities

NACA had several important research centers:

- Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory in Hampton, Virginia

- Ames Aeronautical Laboratory at Moffett Field

- Aircraft Engine Research Laboratory (now Lewis Research Center)

- Muroc Flight Test Unit at Edwards Air Force Base

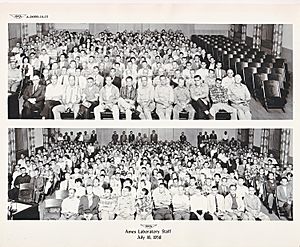

In 1922, NACA had 100 employees. By 1938, it had 426. Staff were even allowed to work on their own unofficial research projects, as long as they were not too strange. This led to many big discoveries.

Some of NACA's key breakthroughs include:

- "Thin airfoil theory" (in the 1920s)

- The "NACA cowling" for engines (in the 1930s)

- The "NACA airfoil" series (in the 1940s)

- The "area rule" for supersonic aircraft (in the 1950s)

In 1941, NACA did not want to increase the speed in their wind tunnels. This slowed down Lockheed's work on solving a problem with the Lockheed P-38 Lightning plane at high speeds.

NACA's large wind tunnel at Langley could only reach 100 miles per hour. The tunnels at Moffett could only reach 250 miles per hour. Lockheed engineers needed much faster speeds. General Henry H. Arnold stepped in and made NACA build new high-speed wind tunnels. By late 1942, a Moffett wind tunnel could reach Mach 0.75 (about 570 miles per hour).

Wind Tunnels

NACA's first wind tunnel opened at Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory on June 11, 1920. This was the first of many famous NACA and NASA wind tunnels. These tunnels helped engineers test new ideas in aerodynamics (how air moves around objects).

Some of NACA's early wind tunnels were:

- Atmospheric 5-foot wind tunnel (1920)

- Variable Density Tunnel (1922)

- Propeller Research Tunnel (1927)

- High-speed 11-inch wind tunnel (1928)

- Vertical 5-foot wind tunnel (1929)

- Atmospheric 7- by 10-foot wind tunnel (1930)

- Full-scale 30- by 60-foot tunnel (1931)

NACA's Role in World War II

Before World War II, NACA helped create several designs that were very important in the war. When a big engine company had trouble making superchargers for the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bomber to fly high, NACA engineers solved the problem. They created new ways to test and build superchargers. This made the B-17 a key aircraft in the war.

The designs and information from NACA's work on the B-17 were used in almost every major U.S. military engine during the war. Most U.S. aircraft used some form of forced induction (like superchargers) based on NACA's research. Because of this, U.S. planes had a big power advantage above 15,000 feet, which enemy forces could not match.

After the war started, the British government asked North American Aviation for a new fighter plane. The Curtiss P-40 Warhawk was too old. So, North American started designing a new plane. The British government chose a wing shape developed by NACA for this new fighter. This wing made the plane perform much better than older models. This aircraft became famous as the North American Aviation P-51 Mustang.

Supersonic Flight Research

The Bell X-1 was the first plane to fly faster than the speed of sound (Mach 1). Even though the Air Force ordered it and test pilot Chuck Yeager flew it, NACA was officially in charge of its testing and development. NACA collected the data and did most of the research. Much of the research came from NACA engineer John Stack, who led NACA's compressibility division. Compressibility is a big problem when planes get close to Mach 1. NACA's earlier wind tunnel tests for the Lockheed P-38 Lightning helped solve this.

The X-1 program began in 1944. A former NACA engineer working for Bell Aircraft asked the Army for money to build a supersonic test plane. Since neither the Army nor Bell had experience in this area, NACA's Compressibility Research Division provided most of the research. Because NACA was so important, John Stack, along with the owner of Bell Aircraft and Chuck Yeager, received the Collier Trophy.

In 1951, NACA Engineer Richard Whitcomb discovered the area rule. This rule explained how air flows over an aircraft at near-supersonic speeds. This discovery helped design planes like the Convair F-102 and the F11F Tiger. The F-102 was supposed to be a supersonic fighter, but it couldn't break the sound barrier. NACA engineers quickly solved the problem by applying the area rule. Planes that were changed to use this rule were called "area ruled" aircraft. This allowed the F-102 to fly faster than sound. The F-11F was designed with the area rule from the start, so it could break the sound barrier easily.

Because the area rule was kept secret at first, it took a few years for Whitcomb to get credit. In 1955, he also won the Collier Trophy for his work.

The most important plane designed using the area rule was the B-58 Hustler. It was redesigned to use the area rule, which greatly improved its performance. This was the first U.S. supersonic bomber, able to fly at Mach 2. The area rule is now used in designing all planes that fly at or above the speed of sound.

NACA's experience was a strong example for research during World War II, for government labs after the war, and for its successor, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

NACA also helped develop the North American X-15, the first aircraft to fly to the "edge of space." NACA's wing designs are still used on modern airplanes today.

Becoming NASA

On November 21, 1957, Hugh Latimer Dryden, NACA's director, created the Special Committee on Space Technology. This committee, also called the Stever Committee, was formed to bring together different parts of the government, private companies, and universities. Their goal was to use their knowledge to create a space program.

This happened after the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1 in October 1957. This event, known as the Sputnik crisis, made the U.S. realize it needed its own strong space program.

On January 14, 1958, Hugh Dryden wrote a paper called "A National Research Program for Space Technology." He said it was very important for the U.S. to have an "energetic program of research and development for the conquest of space." He suggested that a civilian agency, like NACA, should lead the scientific research for space.

On March 5, 1958, James Rhyne Killian, who advised the President on science, wrote to President Dwight D. Eisenhower. He suggested creating NASA based on a "strengthened and redesignated" NACA. He pointed out that NACA was already a working research agency with 7,500 employees and $300 million worth of facilities. He believed NACA could quickly expand its research for space.

Members of the Special Committee on Space Technology

Here are some of the members of the committee, as of their meeting on May 26, 1958:

- Edward R. Sharp, Director of the Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory

- Colonel Norman C Appold, US Air Force

- Abraham Hyatt, Department of the Navy

- Hendrik Wade Bode, Director of Research, Bell Telephone Laboratories

- William Randolph Lovelace II, Lovelace Foundation

- S. K Hoffman, General Manager, Rocketdyne Division, North American Aviation

- Milton U Clauser, Director, Aeronautical Research Laboratory

- H. Julian Allen, Chief, High Speed Flight Research, NACA Ames

- Robert R. Gilruth, Assistant Director, NACA Langley

- J. R. Dempsey, Manager, Convair-Astronautics

- Carl B. Palmer, Secretary to Committee, NACA Headquarters

- H. Guyford Stever, Chairman, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Hugh L. Dryden, Director, NACA

- Dale R. Corson, Department of Physics, Cornell University

- Abe Silverstein, Associate Director, NACA Lewis

- Wernher von Braun, Director, Development Operations Division, Army Ballistic Missile Agency

Images for kids

-

Brig. Gen. George P. Scriven, Chairman 1915–1916

-

Charles Doolittle Walcott, Chairman 1920–1927

-

Vannevar Bush, Chairman 1940–1941

-

Lt. Gen. James H. Doolittle, Chairman 1957–1958

See also

In Spanish: Comité Asesor Nacional para la Aeronáutica para niños

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |