Colonial history of Missouri facts for kids

The Colonial history of Missouri tells the story of how the French and Spanish explored and settled the land that became Missouri. This period lasted from 1673 until 1803, when the United States took control through the Louisiana Purchase.

Contents

Early Explorers and Native American Tribes

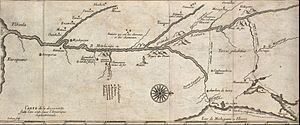

In May 1673, a French priest named Jacques Marquette and a French trader named Louis Jolliet traveled down the Mississippi River in canoes. They explored the area that is now Missouri. Marquette's map from 1673 was the first to use the word "Missouri." It referred to both a Native American group and a nearby river.

However, the French usually called this land part of the Illinois Country. In 1682, another French explorer, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, claimed a huge area called the Louisiana Territory for France. He built trading posts to create a trading empire, but he died before he could finish his plans.

In the late 1600s, France wanted to settle central North America. They aimed to boost trade and stop England from gaining too much power. French explorers like Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville and Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville set up towns like Biloxi (1699) and Mobile (1701) on the Gulf Coast. Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac founded Detroit in 1701 near the Great Lakes. From these towns, fur traders and missionaries traveled, building strong relationships with Native American tribes. This helped France control the middle of the continent.

While Marquette and La Salle passed through Missouri, they didn't set up permanent bases there. The first to do so was Pierre Gabriel Marest, a Jesuit priest. In 1700, he started a mission on the west bank of the Mississippi River, near the mouth of the River des Peres. Marest and some French settlers were joined by the Kaskaskia people. The Kaskaskia hoped the French would protect them from the Iroquois tribe. Marest learned their language and built cabins, a chapel, and a small fort. However, the Sioux tribe was upset about the Kaskaskia moving onto their lands. In 1703, the Sioux forced Marest to move the mission to Kaskaskia, in Illinois.

For a long time, the Mississippi and Missouri rivers were the main ways to travel and communicate in the region. Fur traders started using the Missouri River in the 1680s. By 1703, over a hundred traders were traveling along these rivers. These early traders met two main tribes in what would become Missouri: the Missouri and the Osage.

The Missouri people lived in a main village in northern Saline County, Missouri. They were semi-sedentary, meaning they lived in their village for planting and harvesting, but hunted at other times. The Missouri became friends with the French and even helped defend Detroit. The Osage tribe was also important in Missouri's history. They lived along the Osage River in Vernon County, Missouri and near the Missouri village. Like the Missouri, the Osage lived in semi-permanent villages and had horses.

The French presence brought big changes to the Native American tribes in Missouri. While interactions were often friendly, European diseases and firearms had a negative impact. Diseases like smallpox caused many deaths among the Missouri tribe. The Osage tribe was less affected. Also, relying on European goods changed their traditional ways of making crafts. Increased hunting for trade also changed some Osage customs.

French Settlements and Government

In the 1710s, the French government wanted to develop Louisiana more. In 1717, King Louis XV allowed a Scottish banker named John Law to create a company to manage colonial growth. This company, first called the Company of the West and later the Company of the Indies, had a monopoly on trade and mines in Louisiana. In return, it had to bring 6,000 white settlers and 3,000 enslaved black people to the territory. The Illinois Country, which included Missouri, was part of this plan.

Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville founded New Orleans in 1718. Pierre Dugué de Boisbriand was put in charge of the Illinois Country.

Boisbriand ordered the building of Fort de Chartres in Illinois, which became the company's headquarters. The company then sent people to look for lead and silver in areas of present-day Madison, St. Francois, and Washington counties in Missouri. Philip Francois Renault was put in charge of these mines. In 1723, Boisbriand gave land to Renault in areas known as the Old Mines and Mine La Motte.

Mining was hard work, and white laborers demanded high pay. So, Renault brought five enslaved black people to work in the mines. These were the first enslaved black people in Missouri. Despite these efforts, problems like bad weather and Native American hostility slowed down mining. Renault sold his lands in 1742 without making much profit.

In 1722, the company sent Étienne de Veniard, Sieur de Bourgmont to Missouri. His job was to protect French trade on the Missouri River from Spanish influence. In 1723, Bourgmont and his group built Fort Orleans in present-day Carroll County. Within a year, Bourgmont made alliances with local Native American tribes. In 1725, he even took some of them to Paris to show them off. Fort Orleans was abandoned in 1728 because the company was losing money.

During the 1730s and 1740s, French control over Missouri remained weak, and there were no permanent French towns on the west bank of the Mississippi River. However, French fur traders continued to travel up the Missouri River and trade with Native Americans. In 1739, two traders, Paul and Pierre Mallet, even journeyed from Missouri to Santa Fe, New Mexico. In 1744, a French commander gave fur trading rights along the Missouri River to Joseph Deruisseau. He built a small fort, Fort de Cavagnal, near present-day Kansas City, Missouri. This fort disappeared by 1764.

French settlers stayed on the east bank of the Mississippi at Kaskaskia and Fort de Chartres until 1750. That year, the new settlement of Ste. Genevieve, Missouri was started. Ste. Genevieve grew slowly at first because it was on a muddy floodplain. By 1752, it had only 23 full-time residents. Even though it was near lead mines and salt springs, most people who came in the 1750s and 1760s were farmers. They mainly grew wheat, corn, and tobacco.

Spanish Period: 1762–1803

Soon after Ste. Genevieve was founded, France and England fought over control of the Ohio Valley. This led to the French and Indian War in 1754. Britain won the war, and France lost all its land in North America. In November 1762, France secretly gave Spain control of Louisiana in the Treaty of Fontainebleau. About 1,000 French settlers lived in Missouri in small farming villages along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers.

News of the treaty traveled slowly, reaching Louisiana only in 1765. Before that, the French governor of Louisiana gave a trade monopoly over Missouri to two merchants, Gilbert Antoine de St. Maxent and Pierre Laclède. In August 1763, Laclede and his stepson Auguste Chouteau left New Orleans for Missouri. In February 1764, they founded St. Louis on high bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River.

When the British arrived at Fort de Chartres in October 1765, many French settlers worried about living under British rule. Laclede encouraged them to move to Missouri. So, many French settlers moved across the river to the new Spanish territory.

| Settlement | Founding |

|---|---|

| Mine La Motte | 1717 settlement |

| Ste. Genevieve | 1750 |

| St. Louis | 1764 |

| Carondelet | 1767 |

| St. Charles | 1769 |

| Mine à Breton | 1770 |

| New Madrid | 1783 |

| Florissant | 1786 |

| Commerce | 1788 |

| Cape Girardeau | 1792 |

| Wolf Island | 1792 |

Spanish Rule in Missouri

The first Spanish military leader, Captain Francisco Ríu y Morales, was not very good at his job. His soldiers complained and deserted, and food was scarce. The first Spanish governor of Louisiana, Antonio de Ulloa, removed him. Later Spanish leaders were more capable, but Spain still struggled to govern such a large area.

Both of Missouri's main settlements, Ste. Genevieve and St. Louis, grew as French people moved from British-controlled Illinois. Ste. Genevieve often had floods, but in the 1770s, its population of 600 made it slightly larger than St. Louis. Ste. Genevieve balanced fur trading with farming.

Early St. Louis focused a lot on fur trading. This sometimes led to food shortages, earning the city the nickname 'Paincourt,' meaning 'short of bread.' South of St. Louis, a smaller town called Carondelet was started in 1767, but it never grew very large. A third important settlement began in 1769 when Louis Blanchette, a Canadian trader, set up a trading post. This post eventually grew into the town of St. Charles.

Challenges with the British

Spanish officials in Missouri often had to deal with the wishes of the mostly French population. They also faced repeated visits from British traders and attacks from hostile Native American tribes. American settlers were also starting to arrive.

To reduce British influence, Spain tried to encourage more French settlers to move from Illinois to Missouri. In 1778, Spain offered land and supplies to Catholic immigrants. However, few settlers took these offers. A second Spanish effort against the British was more successful. In the late 1770s, Spanish officials openly supported American rebels fighting against British rule in the American War of Independence. Spanish officials in St. Louis and Ste. Genevieve helped supply George Rogers Clark during his military campaign in 1779.

However, helping the Americans meant risking a British attack. In June 1779, Spain declared war on Britain. By March 1780, St. Louis was warned of a British attack, and the Spanish built Fort San Carlos. In late May 1780, a British war party attacked St. Louis. The town was saved, but 21 people were killed, 7 wounded, and 25 taken prisoner.

After the American victory, Spain kept Louisiana, but the land east of the Mississippi River became part of the United States. American settlers began crossing into Spanish territory. Instead of stopping them, Spanish officials started to encourage American immigration. They hoped this would make the province economically successful.

As part of this plan, in 1789, Spanish diplomats encouraged George Morgan, an American military officer, to start a new colony in southern Missouri. This colony, named New Madrid, started well. However, Louisiana's governor, Esteban Rodríguez Miró, thought Morgan's colony was flawed because it didn't guarantee loyalty to Spain. New Madrid's early American settlers and Morgan left, and New Madrid became mainly a hunting and trading post.

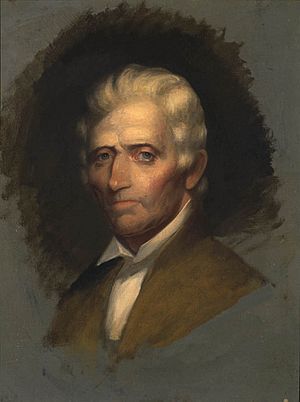

In the early 1790s, both Governor Miró and his successor, Francisco Luis Héctor de Carondelet, were not keen on American immigration to Missouri. But when the Anglo-Spanish War began in 1796, Spain again needed more settlers to defend the region. So, Spain started advertising free land and no taxes in its territory to people in American cities. Americans responded with a wave of immigration. Among these American pioneers was Daniel Boone, who settled with his family after being encouraged by the governor.

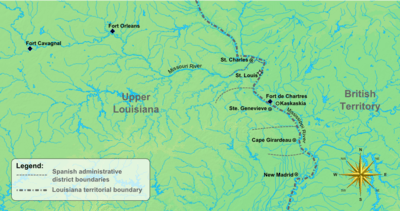

To better govern Missouri, the Spanish divided the province into five districts in the mid-1790s: St. Louis, St. Charles, Ste. Genevieve, Cape Girardeau, and New Madrid. Cape Girardeau was the newest, founded in 1792 by trader Louis Lorimier. St. Louis was the largest district, serving as the capital and trade center. By 1800, its population was nearly 2,500. Other settlements in the St. Louis district included Florissant, settled in 1785, and Bridgeton, settled in 1794. Both were popular with immigrants from the United States.

American settlers greatly changed Missouri. By the mid-1790s, Spanish officials realized that American Protestant immigrants were not interested in converting to Catholicism or being truly loyal to Spain. Despite a brief attempt to allow only Catholic immigrants, the large number of Americans changed the lifestyle and even the main language of Missouri. By 1804, more than three-fifths of the population was American. Since Spain wasn't getting much back from its investment in the colony, it negotiated to return Louisiana, including Missouri, to France in 1800. This was made official in the Treaty of San Ildefonso.

By 1800, most people in Upper Louisiana lived in a few towns along the Mississippi River in what is now Missouri. Travel between towns was mostly by river. Farming was the main economic activity, and most farmers also raised animals. Fur trading, lead mining, and salt making were also important jobs in the 1790s.

Daily Life in Spanish Missouri

Religion was a strong part of life in Spanish Missouri. The Catholic Church had been important since the first settlements. The Jesuits were the main religious authority, but the French removed them in 1763. This, along with the transfer to Spanish control, caused a shortage of priests. Until 1773, Missouri towns didn't have permanent priests. Traveling priests from the east side of the Mississippi served the residents.

In the 1770s and 1780s, Ste. Genevieve and St. Louis gained resident priests. In the 1790s, St. Charles and Florissant had to share a priest, even though both had built churches. Both the French and Spanish governments supported the church financially. They also banned Protestant services in the colony. However, Protestant ministers often visited settlements privately, and rules against Protestants living there were rarely enforced. Historian William E. Foley said that Spanish Missouri had a "de facto form of religious toleration," meaning people were generally allowed to practice their faith without strict rules.

Social classes were somewhat flexible during the Spanish period. There were no aristocrats. The highest class was based on wealth and included a mix of Creole merchants who were often related. Below them were artisans and craftsmen. Then came laborers, like boatmen, hunters, and soldiers. Near the bottom were free black people, servants, and coureur des bois (independent fur traders). Enslaved black and Native American people formed the lowest class.

Crime and misbehavior happened in Spanish Missouri, but officials dealt with them quickly. In 1770, a trader who mocked Spanish rules outside a church in St. Louis was banished from the colony for ten years. That same year, a laborer was banished for stealing. In the late 1770s, nightly patrols in St. Louis stopped a series of robberies. Spanish soldiers were often accused of fighting and stealing.

Women in the region were responsible for many household tasks. This included preparing food and making clothes. French women were known for their cooking, which mixed French dishes like soups with African and Creole foods like gumbo. Colonists also ate local meats like deer, squirrel, rabbits, and bear, but they preferred beef, pork, and fowl. Most food was local, but sugar and liquor were imported until the late Spanish period.

Women also raised children, provided basic schooling, and nursed the sick. Diseases like malaria, whooping cough, and scarlet fever were common. Malaria especially affected low-lying settlements like Ste. Genevieve. Smallpox only became a problem in the late 1700s. Schools were private, with tutors teaching classes. Small schools operated off and on in St. Louis and Ste. Genevieve in the 1780s and 1790s. A private English-language school opened in New Madrid in the late 1790s. Wealthy families sometimes sent their children to other regions for education. For example, François Vallé sent his son to New York City in 1796, and Auguste Chouteau sent his oldest son to Canada in 1802.

The enslaved black population in Missouri was 38% in 1772, but it decreased to 20% by 1803. Enslaved people worked as household servants, in mines, in fields, and in transportation. French and Spanish laws offered them some protections because they were seen as an economic investment. These laws included rules against imprisonment and death. Spanish law allowed enslaved people to own property, be part of lawsuits, work for themselves, and buy their freedom.

Food was plentiful, wars were rare, and birth rates were high. Because of this, the French population grew to about 10,000 people by 1803.

Images for kids

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |