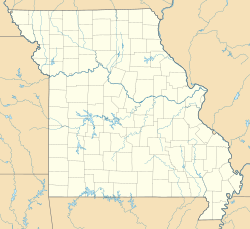

Old Mines, Missouri facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Old Mines

La Vieille Mine

|

|

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| State | Missouri |

| County | Washington |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central(CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CT) |

Old Mines (which is La Vieille Mine in French) is a small, unincorporated community in southeast Missouri. It was settled by French colonists in the early 1700s. At that time, this area was part of New France, known as the Illinois Country.

The first settlers came here to mine for lead. Their families still live in the area today. Because they were quite isolated, they kept their unique French culture alive well into the 1900s. Even in the late 1980s, about a thousand people still spoke the local Missouri French language. This special group of people is sometimes called "paw-paw French." They live in parts of Washington, Jefferson, and St. Francois counties. The community of Old Mines itself is in Washington County, about six miles north of Potosi.

Contents

Discovering Lead in Early Missouri

The southeast Missouri lead district has the largest amount of galena in the world. Galena is a type of ore that contains lead. Native Americans in the region knew about this ore. Early French explorers learned about it from them.

In 1700, a French priest named Father Jacques Gravier wrote in his journal about finding rich lead ore. It was about 36 to 39 miles from the mouth of the Meramec River. The Big River, which flows into the Meramec, was often called the Little Meramec. The lead was likely found near the Big River's source, in areas like Mineral Fork or Old Mines Creek. This is where some of the first mining happened.

French Explorers Search for Silver

The French sent several groups to Missouri to look for silver. Silver is sometimes found with lead ore. These groups were not well-prepared. One group was led by Jacques de Lochon, who was a smelter from Paris. Another was led by La Renaudière. Neither group found much silver, but Renaudière did manage to melt some low-quality lead.

In 1720, Philippe François Renault arrived with professional miners. Renault successfully found and mined large amounts of lead in the Old Mines area. In 1723, he received a land grant for about 9 square leagues (around 17.8 square miles). The exact spot of Renault's mines is not known. However, the village of Old Mines was definitely a settlement by 1748. It was listed as village des mines (village of the mines).

Challenges and Changes in Mining

The discovery of Mine à Breton in the 1770s drew many miners away from Old Mines. But Old Mines was only about 5 to 6 miles north, so some miners continued to live there. They would travel to work at Mine à Breton.

It's not clear if Old Mines was always lived in during the late 1700s and early 1800s. There might have been problems from attacks by the Osage tribe. Also, people complained that mining waste was polluting Old Mines Creek, forcing some to leave their homes.

However, by 1797, there were enough people to ask for land for farming. This request was not officially approved. But it might have helped stop an American miner named Moses Austin from claiming the land. Austin had started bigger mining operations at Mine à Breton.

Land Ownership and the Louisiana Purchase

Moses Austin's success at Mine à Breton made people from Ste. Genevieve and St. Louis more interested in the Old Mines area. They hired workers and slaves to mine lead there. When news arrived that Louisiana was being given back to France from Spain, people became worried about who owned the land. Before this, land ownership was not a big concern for the French settlers.

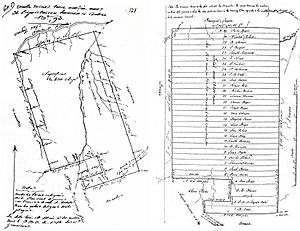

In 1803, both local residents and distant landowners asked for land together. With help from wealthy people in St. Louis and Ste. Genevieve, their request was approved. The petition was for land to farm, about 400 arpents (338 acres) per family. French law only gave free land for farming. Lieutenant Governor Delassus approved the request on June 4, 1803, for a total of 13,400 arpents (17.8 square miles).

The land was divided into 31 long, narrow plots. These plots were given out by a lottery. This lottery did not consider where people actually lived or mined. Most French settlers ignored these new ownership assignments. They continued to live where they always had, mainly in Old Mines village. Most of them sold their lottery-assigned land to outsiders within a year.

After the Americans took control of the area with the Louisiana Purchase, there was a rush to prove land claims. Many of these claims were fake. It took years to sort out who owned what. John Smith T, a business rival of Moses Austin, bought some of the land at Old Mines. He tried to claim even more, which made ownership unclear. But in 1833, the original land grant was officially recognized for the first claimants.

Today, the Old Mines land grant still exists. It is one of the old colonial grants that stands out from the regular American Public Land Survey System grid. You can see the pattern of long, narrow plots in aerial photos.

Why Old Mines Stayed Isolated

Most of the land in Old Mines was bought by people who didn't live there. These were speculators who had no lasting interest in the area. So, the French people continued to dig for lead as they always had, without much interference.

Meanwhile, many new Americans moved into the Missouri territory. The French had settled the region lightly. By 1820, Missouri was mostly Americanized. Only a few French communities, like Ste. Genevieve and Old Mines, remained. Ste. Genevieve kept its French culture for a while because it had a large French population. But as a business center, it attracted many newcomers and eventually became more American. However, few Americans wanted to farm in the Old Mines region because its soil was thin and rocky.

Changes in Mining and Economy

By the mid-1800s, the easy-to-find lead on the surface was gone. But in 1867, the state geologist still reported small-scale mining around Old Mines. After the Civil War, lead mining grew with new, deeper mining methods. This happened in new areas east of Potosi, moving economic activity even further from Old Mines.

In 1874, mining for "tiff" (which is what barite is called locally) began in the Old Mines area. Tiff could be dug by hand from near the surface, much like lead had been for generations. This allowed the community to keep supporting itself and its way of life. Men would dig tiff a few days a week to support their families. They also grew food in their home gardens.

Eventually, the wagon road Moses Austin built to carry ore to Herculaneum (which passed through Old Mines) was replaced by a railroad that didn't go through Old Mines. This made the area even more isolated.

Cultural Differences and Separation

The French people in Old Mines were culturally isolated even before they became geographically isolated. The Americans who developed the lead industry didn't care about the French, except for their labor and their ore. Moses Austin never learned French. When he planned the town of Potosi, he didn't even include the French village of Mine à Breton.

The French didn't like that Americans controlled the economy. Unlike in Ste. Genevieve, there were no wealthy French families in Old Mines to help them. When the Osage tribe attacked in 1799 and 1802, the French did not help the Americans fight. By the time geographic isolation began around the Civil War, the French people were already living separately. They had their own language, customs, and communities.

Missouri French Language and Culture

Because it was so isolated, the Old Mines area became a special place for Missouri French language and culture. This dialect developed in the 1600s when the upper Mississippi River Valley was part of the French colony of Upper Louisiana. It was once spoken widely in what is now Missouri and Illinois. It became one of the three main types of French in the United States, along with Louisiana French and Acadian French. However, it started to disappear as British and later American settlers moved into the area.

Speakers of this dialect called themselves Créoles. They were sometimes known as "paw-paw" French. This name was sometimes used by the people themselves. It was described as a "fun-loving insult" meaning a French Creole person was "so poor that he lived on pawpaw fruit in the summer and possum in the winter."

Studying the Missouri French Language

By the 1900s, Old Mines was the only place in Missouri where Missouri French was still widely spoken. Linguists (people who study languages) began to study the dialect. W. M. Miller, an American French professor, visited in the late 1920s. He found that the local French was only a spoken language. Most people could not read or write English, and very few had ever seen French written down.

Miller also noticed that English words were mixed into French sentences. For example, "Anyhow, je ne sais pas" (meaning "Anyway, I don't know"). English words were also used for new items that the French people didn't have names for, like "un can de maiz" (a can of corn). Still, he felt the spoken French was as grammatically correct as that spoken by farmers in France. The language has been described as having a Cajun vocabulary with a Québécois pronunciation.

Another linguist, J.-M. Carrière, came to Old Mines in the 1930s and 1940s. He found about 600 French-speaking families there. Carrière studied the dialect and recorded 73 folk tales from local storytellers. He also noted that Missouri French was heavily influenced by English. Many English words and even whole phrases were borrowed or translated into the dialect.

Both linguists saw that French was dying out in Old Mines. Miller reported that children couldn't speak it, and young people wouldn't. Carrière said that more English and more connection to the outside world weakened the language. Young people found that speaking French was not useful outside their homes. As late as the 1980s, there were still about a thousand speakers. But most were older, aged 60 and above. Today, the language is almost gone as an everyday language. Only a few elderly people can still speak it.

Unique Aspects of Old Mines Culture

Traditional French Creole culture in Old Mines focused on the extended family and the local French community. They had frequent celebrations. Family homes were often built close together.

The special type of home built by Missouri French people was a single story. It had a wide roof that sloped gently into a roof for a porch (called a gallery). This gallery ran along the wide side of the house, or sometimes all around for wealthier families. This style is still used for new homes in the area today.

The French Creole people are mostly Catholic. A mission priest from Ste. Genevieve first served them. A log church was built in Old Mines in 1820. This was replaced by the brick St. Joachim parish church in 1831. St. Joachim is one of the oldest standing churches in Missouri. It is three years older than St. Louis's Old Cathedral. It is still used and is a center of community life.

How Old Mines Became More American

Many things happened in the early 1900s that broke down the community's isolation. This sped up their assimilation into American culture. Paved state highways in the 1920s reduced the area's physical isolation. Missouri Route 21 now runs through the center of the Old Mines region.

Cultural isolation was also affected by World War I and especially World War II. Many young men were required to join the military. This exposed them to the wider world. In the 1930s, the prices for tiff dropped. This ended over 200 years of living off small-scale mining.

Young men left to find work in St. Louis and other places. It became hard for the archdiocese (church leaders) to keep French-speaking priests for just one parish. So, church services were given only in English. Also, required education in English-only schools became normal.

Efforts to Preserve the Culture

The Old Mines Area Historical Society – La Société Historique de la Région de Vieille Mine – works to save and promote the French culture and history of the region. They have created an outdoor museum of historic buildings in Fertile, Missouri. Dr. Rosemary Hyde Thomas, a scholar of the region, has worked to strengthen the culture. The Rural Parish Workers of Christ the King in Fertile also help. Historian and musician Dennis Stroughmatt learned French there. He promotes the language and folk music of Old Mines.

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |