General Order No. 11 (1863) facts for kids

General Order No. 11 was a special rule made by the Union Army during the American Civil War. It was issued on August 25, 1863. This order made people living in four rural counties in western Missouri leave their homes.

The order came from Union General Thomas Ewing, Jr.. It affected everyone in these areas, no matter if they supported the Union or the Confederacy. People who could prove they were loyal to the Union could stay. But they had to leave their farms and move to towns near army bases. Those who could not prove their loyalty had to leave the area completely.

This order was meant to stop pro-Confederate fighters, called guerrillas, from getting help from people in the countryside. However, the order was very strict. It made many regular people upset. In the end, it actually made it easier for guerrillas to get supplies. The order was canceled in January 1864. This happened when a new general took charge of the Union forces there.

Contents

Why the Order Was Made

General Order No. 11 was issued four days after the Lawrence Massacre. This was a terrible event on August 21, 1863. A Confederate fighter group led by William Quantrill attacked Lawrence, Kansas. They killed many men and boys.

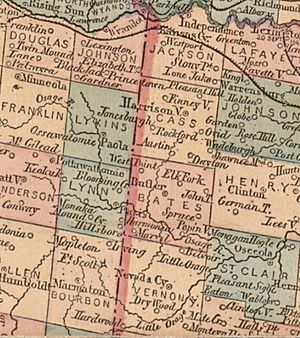

The Union Army believed Quantrill's fighters got help from people in four Missouri counties. These counties were on the Kansas border, south of the Missouri River. They were Bates, Cass, Jackson, and part of Vernon. After the attack in Lawrence, Union forces wanted to stop such raids. They decided to do whatever it took, even if it hurt innocent people.

General Thomas Ewing had lost friends in the Lawrence attack. So, he issued Order No. 11. His order forced almost everyone to leave these counties. Only those living within one mile of certain towns could stay. These towns included Independence, Hickman Mills, Pleasant Hill, and Harrisonville. Also, a part of Kansas City, Missouri was safe.

President Abraham Lincoln approved Ewing's order. But he warned that soldiers must not let angry groups take justice into their own hands. This warning was often ignored. General Ewing's boss, Major General John Schofield, also thought the order was needed. He even called it "wise and just."

What General Order No. 11 Said

General Order № 11.

Headquarters District of the Border,

Kansas City, August 25, 1863.1. All persons living in Jackson, Cass, and Bates counties, Missouri, and in that part of Vernon included in this district, except those living within one mile of the limits of Independence, Hickman's Mills, Pleasant Hill, and Harrisonville, and except those in that part of Kaw Township, Jackson County, north of Brush Creek and west of Big Blue, are hereby ordered to remove from their present places of residence within fifteen days from the date hereof.

Those who within that time establish their loyalty to the satisfaction of the commanding officer of the military station near their present place of residence will receive from him a certificate stating the fact of their loyalty, and the names of the witnesses by whom it can be shown. All who receive such certificates will be permitted to remove to any military station in this district, or to any part of the State of Kansas, except the counties of the eastern border of the State. All others shall remove out of the district. Officers commanding companies and detachments serving in the counties named will see that this paragraph is promptly obeyed.

2. All grain and hay in the field or under shelter, in the district from which inhabitants are required to remove, within reach of military stations after the 9th day of September next, will be taken to such stations and turned over to the proper officers there and report of the amount so turned over made to district headquarters, specifying the names of all loyal owners and amount of such product taken from them. All grain and hay found in such district after the 9th day of September next, not convenient to such stations, will be destroyed.

3. The provisions of General Order No. 10 from these headquarters will be at once vigorously executed by officers commanding in the parts of the district and at the station not subject to the operations of paragraph 1 of this order, and especially the towns of Independence, Westport and Kansas City.

4. Paragraph 3, General Order No. 10 is revoked as to all who have borne arms against the Government in the district since the 20th day of August, 1863.

By order of Brigadier General Ewing.

H. Hannahs, Adjt.-Gen'l.

How the Order Was Carried Out

Order No. 11 was meant to stop Confederate attacks. It also aimed to control Union groups who wanted revenge. These Union groups, like the Jayhawkers, were very angry after Quantrill's Raid. General Ewing had to deal with both Confederate raiders and these angry Unionists.

One Union leader, James Lane, threatened to lead a force from Kansas into Missouri. He wanted to destroy the four counties mentioned in Ewing's order. On September 9, 1863, Lane gathered almost a thousand Kansans. They marched towards Westport, Missouri, planning to destroy the town. Ewing sent his own soldiers to stop Lane. Faced with a stronger Union force, Lane eventually gave up.

The order was partly meant to punish Missourians who supported the rebels. However, many people in these four counties were loyal to the Union or neutral. In reality, Union troops often acted without thinking. Farm animals were killed. Homes and property were destroyed or stolen. Houses, barns, and other buildings were burned to the ground. Some civilians were killed, even elderly people.

Ewing's four counties became a "no man's land" of destruction. Only charred chimneys remained where homes and towns once stood. These chimneys were nicknamed "Jennison's tombstones" after a Union leader, "Doc" Jennison. This area became known as "The Burnt District." Historian Christopher Philips wrote that the area was called this because so many people were forced to leave and so much property was destroyed. Very few old homes from before the war remain in this area today.

Ewing wanted to show that Union forces would act strongly against Quantrill and other fighters. He hoped this would make revenge attacks unnecessary. He told his troops not to loot or destroy property. But he could not control them. Most of the soldiers were Kansas volunteers. They saw everyone in these counties as rebels whose property could be taken.

Even though Union troops burned most farms and houses, they could not stop Confederates from getting food and supplies. Ewing's order actually had the opposite effect. Instead of stopping the fighters, it gave them easy access to supplies. For example, the fighters could take chickens, hogs, and cattle left behind by fleeing owners. They also found hams, bacon, and horse feed in abandoned buildings.

Ending the Order and Its Impact

Ewing made his order less strict in November. He issued General Order No. 20. This allowed people who could prove their loyalty to the Union to return. In January 1864, General Egbert Brown took command of the border counties. He did not like Order No. 11.

General Brown quickly replaced it with a new rule. This new rule allowed anyone who promised loyalty to the Union to return and rebuild their homes.

Ewing's controversial order greatly changed the lives of thousands of people. Most of them were innocent and not helping the fighters. It is not clear if Order No. 11 really stopped Confederate military actions. No major raids into Kansas happened after it was issued. But historian Albert Castel believes this was due to stronger border defenses and better organized local guards. He also thinks the fighters focused on other parts of Missouri to prepare for General Sterling Price's 1864 invasion.

The terrible destruction and anger caused by Ewing's Order No. 11 lasted for many decades in western Missouri. The affected counties took a long time to recover.

A book called Order No. 11 was written in 1904 by Caroline Abbot Stanley. It tells a story based on these events.

George Bingham's Painting

The American artist George Caleb Bingham was against General Ewing. He called Order No. 11 a "stupid act." He wrote letters to protest it. Bingham told General Ewing, "If you do this order, I will make you famous with my pen and brush." In 1868, he created his famous painting showing what happened because of Ewing's harsh rule. You can see it at the top of this article.

Frank James, a former fighter who was part of the Lawrence raid, is said to have commented: "This is a picture that talks." Historian Albert Castel called it "average art but excellent propaganda."

Bingham was in Kansas City at the time. He described the events he saw:

It is well-known that men were shot down in the very act of obeying the order, and their wagons and effects seized by their murderers. Large trains of wagons, extending over the prairies for miles in length, and moving Kansasward, were freighted with every description of household furniture and wearing apparel belonging to the exiled inhabitants. Dense columns of smoke arising in every direction marked the conflagrations of dwellings, many of the evidences of which are yet to be seen in the remains of seared and blackened chimneys, standing as melancholy monuments of a ruthless military despotism which spared neither age, sex, character, nor condition. There was neither aid nor protection afforded to the banished inhabitants by the heartless authority which expelled them from their rightful possessions. They crowded by hundreds upon the banks of the Missouri River, and were indebted to the charity of benevolent steamboat conductors for transportation to places of safety where friendly aid could be extended to them without danger to those who ventured to contribute it.

Bingham believed that the real troublemakers in western Missouri and eastern Kansas were not Confederate fighters. He thought they were pro-Union Jayhawkers and "Red Legs." He accused them of acting under General Ewing's protection. The Red Legs were a group of about 100 soldiers who wore red leggings. They were scouts for Union troops. People at the time accused them of causing much destruction.

Bingham thought Union troops could have easily beaten the fighters if they had tried harder. However, historian Albert E. Castel disagrees. He says that Ewing tried hard to control the Jayhawkers and stop violence from both sides. Castel also argues that Ewing issued Order No. 11 partly to stop a planned Unionist attack on Missouri. This attack was meant to get revenge for the Lawrence massacre. It was to be led by Kansas Senator Jim Lane.

See also

In Spanish: Orden General N.º 11 (1863) para niños

In Spanish: Orden General N.º 11 (1863) para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |