History of trade unions in the United Kingdom facts for kids

Trade unions are groups of workers who join together to protect their rights and improve their working lives. This article tells the story of how trade unions started and grew in the United Kingdom, from the early 1800s until today.

Early Trade Unions: 1800s

In the early 1800s, it was very hard for workers to form unions in Britain. The government often tried to stop them. But even then, many workers in cities like London were already part of these groups.

In 1824, trade unions became legal. More and more factory workers joined them. They wanted better pay and safer working conditions. Sometimes, workers showed their anger in other ways. For example, the Luddites broke machines they felt were taking their jobs. In Scotland, in 1820, about 60,000 workers went on a general strike. This meant they all stopped working at once. But the strike was quickly ended.

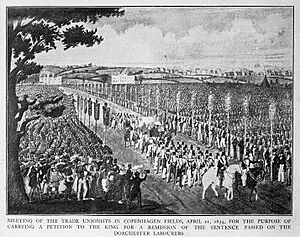

From 1830, people tried to create bigger, national unions. One famous attempt was Robert Owen's Grand National Consolidated Trades Union in 1834. It brought together many different groups. This union helped with protests after the Tolpuddle Martyrs' case. The Tolpuddle Martyrs were six farm workers who were punished for trying to form a union. But Owen's big union soon fell apart.

A key event for unions in Wales was the Merthyr Rising in May 1831. Coal and steel workers in Merthyr Tydfil protested against lower wages and job losses. The protest spread, and the whole area was in rebellion. For the first time, the red flag of revolution was flown. This flag is now used by unions and socialist groups worldwide.

What was Chartism?

In the late 1830s and 1840s, trade unions were less in the spotlight. A big political movement called Chartism became very important. Most union members supported Chartism.

Chartism was a working-class movement that wanted political changes in Britain. It lasted from 1838 to 1858. The movement got its name from the People's Charter of 1838. This charter asked for things like the right for all men to vote. Millions of working people signed petitions and held large meetings to push for these changes.

Chartists mostly used peaceful methods. But some people did get involved in rebellions, especially in South Wales. The government did not agree to their demands. It took another 20 years for more men to get the right to vote.

Chartism was popular with some unions. This was especially true for tailors, shoemakers, carpenters, and masons in London. They worried about many unskilled workers joining their trades. Engineers in Manchester and Glasgow were also very active in Chartism. Many unions took part in the general strike of 1842. This strike spread across 15 counties in England and Wales, and eight in Scotland. Chartism taught union leaders important skills for political action.

New Unions Form in the 1850s

From the 1850s to the 1950s, union activity in textile and engineering industries was mostly led by skilled workers. They wanted to keep their higher pay and status. They focused on controlling how machines were used in factories.

After the Chartist movement ended around 1848, people tried to form new worker groups. The Miners' and Seamen's United Association in the North-East operated from 1851 to 1854. But it also failed due to outside opposition and arguments within the group.

More lasting trade unions were set up from the 1850s. These unions had more money but were often less radical. The London Trades Council was started in 1860. The Sheffield Outrages, which were violent acts by some union members, helped lead to the creation of the Trades Union Congress (TUC) in 1868.

The legal standing of trade unions in the UK was confirmed by a Royal Commission on Trade Unions in 1867. This group agreed that unions were good for both employers and workers. Unions became fully legal in 1871 with the Trade Union Act 1871.

New Unionism: 1889–1893

The "aristocracy of labour" were skilled workers. They were proud of their special skills and formed unions to keep out less skilled workers. The strongest unions in the mid-1800s were for skilled workers, like the Amalgamated Society of Engineers.

Unions were not common for semi-skilled and unskilled workers. Union leaders often avoided strikes. They worried that strikes would use up the union's money and affect their own salaries.

However, a wave of unexpected strikes happened in 1889–1890. These strikes were mostly started by ordinary workers. They succeeded because there were fewer workers coming from the countryside. This gave unskilled workers more power to demand better conditions.

The "New Unionism" movement began in 1889. It aimed to bring unskilled and semi-skilled workers into unions. Ben Tillett was a key leader of the London Dock strike of 1889. He formed the Dock, Wharf, Riverside and General Labourers' Union in 1889. This union had support from skilled workers. Its 30,000 members won better pay and working conditions.

Unions played a big part in creating the Labour Representation Committee. This group later became the Labour Party we know today.

Women in Unions

For a long time, women were mostly left out of trade unions. They were not often members or leaders until the late 1900s. When women did try to get involved, it was often thanks to middle-class reformers. Groups like the Women's Protective and Provident League (WPPL) tried to talk with employers in the 1870s. This group later became the Women's Trade Union League.

Some more radical socialists left the WPPL to form the Women's Trade Union Association. But they did not have much impact. There were a few times in the 1800s when women union members took action themselves. For example, in the 1875 West Yorkshire weavers' strike, women played a central role.

The Labour Party Emerges

The Labour Party started in the late 1800s. People realized there was a need for a new political party. This party would represent the interests of city workers, whose numbers had grown a lot. Also, more men had recently gained the right to vote.

Some union members wanted to get involved in politics. After more people got the right to vote in 1867 and 1885, the Liberal Party supported some union-backed candidates. The first such candidate was George Odger in the Southwark election of 1870.

Around this time, several small socialist groups also formed. They wanted to connect the workers' movement with political ideas. These groups included the Independent Labour Party, the Fabian Society, and the Marxist Social Democratic Federation.

Trade Unions Since 1900

1900–1945: Big Changes

Politics became very important for coal miners. Their unions were strong because miners often lived in villages where coal mining was the only industry. The Miners' Federation of Great Britain formed in 1888. By 1908, it had 600,000 members. Many early Labour politicians came from coal-mining areas.

Worker Unrest: 1910–1914

From 1910 to 1914, there was a lot of worker unrest. Union membership grew hugely in all industries. Workers were most active in coal mining, textiles, and transportation. Much of this unrest came from ordinary workers protesting against falling wages. Union leaders often struggled to keep up with their members' demands. The newer unions for semi-skilled workers were the most active.

The National Sailors' and Firemen's Union led strikes in many port cities across Britain. Local leaders strongly supported the national leaders. For example, the Glasgow Trades Council was very active. In Glasgow, waterfront unions became very strong.

First World War and Unions

Making weapons and supplies was vital during World War I. Many men joined the military, so there was a huge demand for factory workers. Many women took on these jobs temporarily. Trade unions strongly supported the war effort. They reduced strikes and relaxed some work rules.

Union membership doubled from 4.1 million in 1914 to 8.3 million in 1920. The Trades Union Congress (TUC) represented 65% of union members in 1914, rising to 77% in 1920. Labour's standing was very high, and its leaders entered Parliament.

The Munitions of War Act 1915 was passed after a shortage of shells for the army. This law banned strikes and lock-outs. It set up special courts to make sure people worked well. It also temporarily stopped some union rules. The law tried to control where workers could move between jobs. This act was cancelled in 1919, but similar laws were used in World War II.

In Glasgow, the high demand for weapons and warships made unions more powerful. A radical movement called "Red Clydeside" grew there. It was led by strong union members. These industrial areas, once Liberal strongholds, switched to Labour by 1922. Women were especially active in protests about housing. However, the "Reds" worked within the Labour Party and had little power in Parliament. By the late 1920s, their mood changed to despair.

The war led to more union members and more recognition for unions. Unions also became more involved in managing workplaces. Strikes were seen as unpatriotic, and the government tried to keep wages low. After the war, unions became very active trying to keep their gains. But they were usually defeated. Membership grew from 4.1 million in 1914 to 6.5 million in 1918. It peaked at 8.3 million in 1920 before falling to 5.4 million in 1923.

The 1920s and Strikes

After World War I, there were some radical events. The communist takeover in Russia in 1917 partly caused this. Unions, especially in Scotland, were very active. But the government made some compromises. As the economy settled in the early 1920s, unions became less radical.

An exception was the coal miners' union. Miners faced lower wages in a struggling industry. Coal prices were low, and there was strong competition from oil. Britain's old coal mines also had lower output.

The 1926 General Strike was called by the Trades Union Congress to help the coal miners. But it failed. It was a nine-day strike involving one million railway workers, transport workers, printers, and steelworkers. They supported 1.5 million coal miners who had been locked out of their jobs. In the end, many miners went back to work. They had to accept longer hours and lower pay.

In 1927, the government passed a strong anti-union law called the Trade Disputes and Trade Union Act. This law greatly limited union power. It made sympathetic strikes and large protests illegal. It also stopped civil service unions from joining the TUC.

TUC leaders like Ernest Bevin thought the 1926 general strike was a big mistake. Most historians see it as a single event with few long-term effects. But some say it made more working-class voters support the Labour Party. The 1927 Act was mostly cancelled in 1946.

Unions and Foreign Policy

Trade unions generally did not support communism. Many people on the left supported the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939). But the Labour Party leaders did not trust communists.

The TUC, working with the American Federation of Labor, stopped a 1937 plan. This plan would have allowed Soviet trade unions to join the International Federation of Trade Unions (IFTU). The TUC changed its mind in 1938 to let the Russians in. But they opposed it again in 1939 when Stalin and Hitler made a deal.

When Britain entered World War II, the TUC strongly supported the war. They sent leaders to the United States to get American union support. When Hitler invaded Russia in 1941, the TUC also sent leaders to Moscow. They knew Britain needed Russia as an ally against Hitler.

After the war, British unions again took a strong anti-communist stance. However, communists did hold local power in some unions, especially the coal miners' union.

Even though their foreign policy efforts were difficult, British trade unions grew a lot during World War II. The Labour Party's big win in 1945 gave unions a strong voice in national matters. This was especially true with Ernest Bevin as Foreign Minister.

Since 1945: Power and Decline

Trade unions were at their strongest after World War II. They had many members, were well-known, respected, and had political power. Most people accepted their role. Union leaders were heavily involved in the Labour Party. By the 1970s, their power grew even more. But their public image began to decline.

In the 1980s, the Conservative Party, led by Margaret Thatcher, deliberately weakened the union movement. Unions have not recovered their former strength since then.

Winter of Discontent: 1978–1979

Big strikes by British unions during the 1978–1979 "Winter of Discontent" helped cause the fall of James Callaghan's Labour government. Callaghan, who had been a trade unionist himself, asked unions to limit their pay demands. This was part of the government's plan to control high inflation.

His attempt to limit pay rises to 5% led to many official and unofficial strikes. Lorry drivers, rail workers, nurses, and ambulance drivers all went on strike. This created a feeling of crisis across the country. The strikes greatly changed how people planned to vote. In November 1978, Labour had a 5% lead in polls. After the strikes, in February 1979, the Conservatives had a 20% lead.

Thatcher and the 1980s

Callaghan's government fell. Margaret Thatcher's Conservatives won the next general election by a landslide. She brought in new union laws to deal with the worker unrest that had troubled earlier governments. Unions became her strong opponents.

Thatcher believed strong unions stopped economic growth. She passed strict laws that the Conservative Party had avoided for a long time. In 1986, over 6,000 printing workers went on strike in the Wapping dispute. They felt the job terms at The Sun newspaper's new office in Wapping were unfair. They also lost their case.

The National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) had been one of the strongest unions. Their strikes had even caused governments to fall in the 1970s. But the miners were defeated during their 1984–1985 strike. NUM leader Arthur Scargill called a 12-month strike to protest against plans to close coal mines.

The main problem was that the easy-to-reach coal had all been mined. What was left was very expensive to get. The miners were fighting not just for higher wages but for their way of life. This way of life needed to be paid for by other workers. The Union split, and its plan was flawed. In the end, almost all the mines were shut down.

Fewer Union Members

Union membership dropped sharply in the 1980s and 1990s. It fell from 13 million in 1979 to about 7.3 million in 2000. In 2012, union membership went below 6 million for the first time since the 1940s. From 1980 to 1998, the number of employees who were union members fell from 52% to 30%.

Images for kids

-

Protesters in Bristol during the 2011 public sector strikes

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |