Hugh Cleghorn (forester) facts for kids

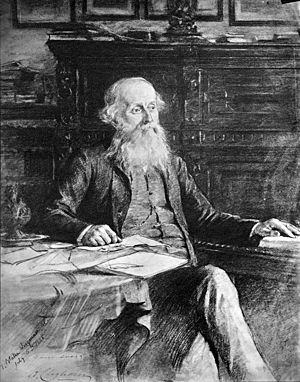

Hugh Francis Clarke Cleghorn (born August 9, 1820 – died May 16, 1895) was a Scottish doctor, botanist, and expert in forests. He was born in Madras, India. People often call him the "father of scientific forestry in India." He was the first person in charge of forests for the Madras area and even worked twice as the main Inspector General of Forests for all of India.

After working in India for many years, Cleghorn returned to Scotland in 1868. There, he helped with the first-ever International Forestry Exhibition. He also advised the government on how to train forest officers. He helped set up classes for botany at the University of St Andrews and for forestry at the University of Edinburgh. A type of plant, Cleghornia, was named after him by another botanist, Robert Wight.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Hugh Cleghorn was born in Madras (which is now Chennai), India, on August 9, 1820. His father worked in the Madras Supreme Court. When Hugh was three years old, his mother passed away.

In 1824, Hugh and his younger brother were sent to Scotland. They lived with their grandfather, Hugh Cleghorn, near St Andrews. His grandfather had been a professor at St Andrews University and was the first British colonial secretary of Ceylon.

Hugh went to school at the Royal High School in Edinburgh. After getting sick, he attended Madras College in St Andrews. In 1834, he started studying at St Andrews University. Living with his grandfather, who was interested in improving his land, Hugh became interested in managing estates, including forests and plants.

In 1837, he went to Edinburgh to study medicine. He learned from a surgeon named James Syme and studied botany (the study of plants) with Robert Graham. He became a doctor from the University of Edinburgh in 1841. The next year, he joined the East India Company as an Assistant Surgeon in Madras.

Working in India

Cleghorn's first job was at the Madras General Hospital. After working in the military, he joined the Mysore Commission in 1845. For the next two years, he was based in Shimoga. He continued to study plants, encouraged by Sir William Jackson Hooker, a famous botanist. Hooker suggested he "study one plant a day for a quarter of an hour."

It was here that Cleghorn started commissioning drawings of plants. He became very interested in economic botany, which is about plants that are useful to people. He also noticed that the teak forests were shrinking a lot.

In 1848, he got sick with "Mysore fever" and went back to Britain for a break. He joined scientific groups like the Botanical Society of Edinburgh. He gave talks about plants, including one on hedge plants. This talk even won him a medal!

At a meeting in 1850, Cleghorn was asked to write a report. This report was about how cutting down too many trees in tropical areas affected the environment. He also helped to organize Indian plant exhibits for the Great Exhibition in London in 1851.

Cleghorn returned to India in 1852. He became a professor of Botany at Madras Medical College. He also became an active member of the Madras Literary Society and the Madras Agri-Horticultural Society. In 1853, he published a book called Hortus Madraspatensis, which listed the plants in the Society's garden.

The Madras Government often asked Cleghorn for advice on plants that could be useful. For example, he wrote about plants that could help hold sand on the Madras beach. Cleghorn also played a big part in the Madras Exhibitions of 1855 and 1857.

Starting the Madras Forest Department

In 1855, the Governor of Madras, Lord Harris, asked Cleghorn to set up a Forest Department for Madras. This department would start protecting forests in a planned way. He was appointed as the Conservator of Forests on December 19, 1856. He held this important job until 1867.

The forests in the Madras area were under great pressure. This was because railways were being built in India. Cleghorn estimated that one mile of railway track needed 1760 wooden sleepers (the pieces of wood that support the rails). These sleepers only lasted about eight years. Wood was also needed to power steam engines and steamships. Cleghorn realized that without careful management, the forests would be destroyed.

It was already known that forests had a big effect on the climate. Cutting down trees could reduce rainfall and river flow. In his 1851 report, Cleghorn explained these problems. He believed that the government needed to play the main role in saving the forests.

In 1860, Cleghorn's hard work convinced the government to ban "kumri." This was a type of shifting cultivation (where farmers clear land by burning it, use it for a few years, and then move on) that he thought was very harmful to the forests.

One of his first actions as Conservator was a trip to Burma in 1857. There, he met Dietrich Brandis, who was also working on teak forests. Cleghorn saw how private businesses were destroying the forests. He believed the government had to protect them.

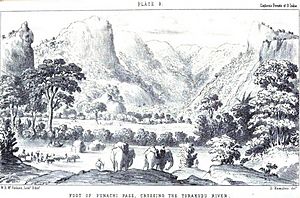

As Conservator, Cleghorn spent much of his time traveling. He surveyed forest resources across the huge territory he was responsible for. He made three major trips, each lasting more than six months, in 1857, 1858, and 1860. He also made shorter trips, including one to the Anamalai Hills in 1859. On this trip, he was joined by Richard Henry Beddome, who later took over Cleghorn's job in Madras. Major Douglas Hamilton, a talented artist, drew pictures of their journey.

On his third forest tour, Cleghorn got sick again. He took a year's leave to go back to Britain in 1861. During this time, he worked with the India Office. This allowed his forest reports to be published as a book called The forests and gardens of South India. This book documented his work in protecting forests in Madras.

While in Scotland, Cleghorn continued to give talks about plants. He also got married to Marjorie Isabella, known as ‘Mabel’, on August 8.

Working for the Forest Department of India

Cleghorn returned to India with Mabel in October 1861. He was asked to survey the forests of the Punjab Himalaya. He continued this work in Lahore, where he was involved in the 1864 Punjab Exhibition. His second book, The Forests of the Punjab (1864), was a collection of his reports from this time.

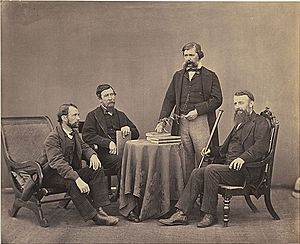

In 1864, Dietrich Brandis and Cleghorn were both appointed as Commissioners of Forests. Three months later, Brandis became the senior Inspector General. They worked together on the Indian Forest Act, which became law on May 1, 1865.

Cleghorn acted as Inspector General twice when Brandis was away. After his second time as Inspector General, Cleghorn returned to Madras. He took a long leave in October 1867. He never returned to India after this and officially retired.

Life After India

In November 1867, Cleghorn met Mabel in Malta. He wrote a report about the farming and plants of Malta and Sicily the next year. Back in Britain, he advised the government on choosing people for the Indian Forest Service.

He was elected president of the Edinburgh Botanical Society in 1868–69. In 1872, he became president of the Scottish Arboricultural Society. He played a key role in setting up a class for forestry at the University of Edinburgh. Cleghorn also shared his ideas with the House of Commons in 1885 about how to teach forestry in Britain.

Cleghorn wrote the entries on ‘Arboriculture’ (the science of growing trees) and ‘Forests’ for the ninth edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica.

Hugh Cleghorn passed away at his home in Stravithie on May 16, 1895.

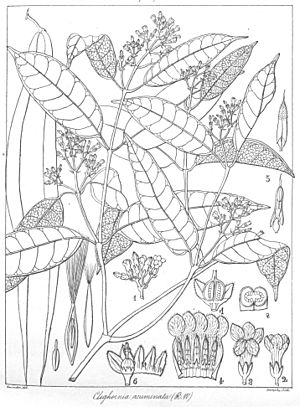

In 1848, his friend Robert Wight named the plant group Cleghornia after him. He did this because Cleghorn was a "zealous cultivator of Botany," meaning he was very enthusiastic about studying plants, especially those useful in medicine.

Botanical Work

Even though Cleghorn didn't describe any new plant species himself, one plant name was incorrectly linked to him.