Ivo Andrić facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ivo Andrić

|

|

|---|---|

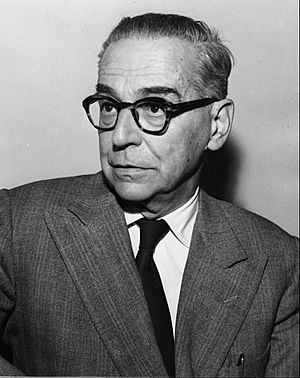

Andrić in 1961

|

|

| Born | Ivan Andrić 9 October 1892 Dolac, Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | 13 March 1975 (aged 82) Belgrade, SR Serbia, SFR Yugoslavia |

| Resting place | Belgrade New Cemetery |

| Occupation |

|

| Language | Serbo-Croatian |

| Nationality | Yugoslav |

| Alma mater |

|

| Years active | 1911–1974 |

| Notable work |

|

| Notable awards |

|

| Spouse |

Milica Babić

(m. 1958; died 1968) |

| Signature | |

|

|

Ivo Andrić (born Ivan Andrić; 9 October 1892 – 13 March 1975) was a famous writer from Yugoslavia. He wrote novels, poems, and short stories. In 1961, he won the Nobel Prize in Literature, which is one of the highest awards a writer can receive. His stories often explored life in his home country, Bosnia, especially during the time it was ruled by the Ottoman Empire.

Andrić was born in Travnik, which was then part of Austria-Hungary and is now in Bosnia and Herzegovina. He went to high school in Sarajevo, where he joined youth groups that wanted to unite the South Slav people. Because of his activities, he was arrested and held by the police during World War I, but he was later released. After the war, he studied history and literature at universities and earned a PhD.

He worked as a diplomat for the Kingdom of Yugoslavia from 1920 to 1941. In 1939, he became Yugoslavia's ambassador to Germany. However, his job ended when Germany invaded Yugoslavia in April 1941. During World War II, Andrić lived quietly in Belgrade and wrote some of his most important books, including The Bridge on the Drina.

After the war, Andrić took on several important roles in Yugoslavia, which was then under communist rule. In 1961, he won the Nobel Prize in Literature. The Nobel Committee praised his "epic force" in telling stories about his country's history and people. After winning the prize, his books became famous worldwide and were translated into many languages. He received many awards in Yugoslavia. Andrić's health got worse in 1974, and he passed away in Belgrade in March 1975.

After his death, the apartment where he lived during World War II in Belgrade became a museum. Many streets in former Yugoslavia are named after him. In 2012, a filmmaker named Emir Kusturica started building a special town in eastern Bosnia called Andrićgrad, named after Ivo Andrić. As the only Nobel Prize winner from Yugoslavia, Andrić was very respected.

Contents

Early Life and Education

His Family and Home

Ivan Andrić was born in a village called Dolac, near Travnik, on October 9, 1892. His parents, Antun and Katarina, were Catholic Croats. He was their only child. His father, Antun, was a silversmith who struggled financially and later worked as a school janitor. Sadly, Antun died of tuberculosis when Ivo was only two years old.

Since his mother was a widow and had no money, she took Ivo to Višegrad. There, he was cared for by his aunt Ana and uncle Ivan Matković, who was a police officer. They had no children and were financially stable, so they raised him as their own. His mother went back to Sarajevo to find work.

Andrić grew up in a country that had changed little since the Ottoman Empire ruled it. Bosnia was a mix of Eastern and Western cultures. Andrić loved Višegrad, calling it his "real home." Even though it was a small town, it gave him many ideas for his stories. Višegrad had different groups of people, mainly Serbs (Orthodox Christians) and Bosniaks (Muslims). From a young age, Andrić watched the local customs closely. These customs and the unique life in eastern Bosnia later appeared in his books. He made his first friends in Višegrad, playing by the Drina River and near the famous Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge.

School Days

Andrić started primary school when he was six years old. He later said these were the happiest days of his life. At age ten, he received a scholarship from a Croat cultural group called Napredak (Progress) to study in Sarajevo. In 1902, he enrolled at the Great Sarajevo Gymnasium, the oldest high school in Bosnia. While in Sarajevo, Andrić lived with his mother, who worked in a rug factory.

Sarajevo was a city with many people from all over Austria-Hungary, so different languages were heard everywhere. The schools focused on supporting the Habsburg Monarchy, which Andrić did not like. He found his studies difficult, especially math, and had to repeat a grade. He even lost his scholarship for a while because of his grades. However, he was excellent at languages like Latin, Greek, and German. He became very interested in literature, influenced by his Croat teachers, Đuro Šurmin and Tugomir Alaupović. Andrić liked Alaupović the most, and they became lifelong friends.

Andrić felt he was meant to be a writer. He started writing in high school, but his mother didn't encourage him much. He published his first two poems in 1911 in a journal called Bosanska vila (Bosnian Fairy), which promoted unity between Serbs and Croats. Before World War I, his poems, essays, and translations appeared in other journals too. He enjoyed writing lyrical reflective prose, which are like poetic essays.

Student Activities

In 1908, Austria-Hungary officially took over Bosnia and Herzegovina. This upset many South Slav nationalists, including Andrić. In late 1911, Andrić became the first president of the Serbo-Croat Progressive Movement (SHNO). This was a secret group in Sarajevo that wanted Serbs and Croats to be united and friendly, and they were against Austria-Hungary's rule. Andrić continued to speak out against the Austro-Hungarians. He also joined another South Slav student group called Young Bosnia.

In 1912, Andrić started studying at the University of Zagreb with a scholarship. He studied math and natural sciences because those were the only fields with scholarships, but he also took Croatian literature classes. He joined student protests, which led to him being warned by the university. In 1913, he moved to the University of Vienna to continue his studies. There, he worked with other South Slav students who wanted to unite all South Slav cultures.

However, the climate in Vienna made Andrić sick with tuberculosis. He asked to leave Vienna for health reasons and moved to Jagiellonian University in Kraków in early 1914. He continued to publish poems, translations, and reviews, starting his literary career as a poet.

World War I Experiences

On June 28, 1914, Andrić heard about the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo. The assassin was Gavrilo Princip, a friend of Andrić's from the Young Bosnia movement. Andrić decided to leave Kraków and return to Bosnia. He traveled to Zagreb and then to Split. As the political situation worsened, he felt uneasy.

Soon after war was declared, Andrić was arrested in Split for "anti-state activities," even though he wasn't involved in the assassination plot. He was moved to prisons in Šibenik, Rijeka, and finally Maribor. While in prison, he read, talked to other prisoners, and learned languages.

In March 1915, the case against Andrić was dropped due to lack of evidence, and he was released. The authorities sent him to the village of Ovčarevo, near Travnik, where he was supervised by Franciscan friars. Andrić became friends with a friar named Alojzije Perčinlić and started researching the history of Bosnia's Christian communities under Ottoman rule. He lived with the Franciscans and helped the priest and taught at the monastery school. His mother even came to visit him and helped as a housekeeper.

Andrić was later moved to a hospital in Sarajevo because of his poor health, which kept him from serving in the army. He then went to Zagreb. In January 1918, he joined other South Slav nationalists in editing a short-lived magazine called Književni jug (Literary South), where he published reviews, plays, and poems. His health got worse, but he recovered and spent the spring of 1918 writing Ex ponto, a book of prose poetry. This was his first published book.

Between the Wars

After World War I, Austria-Hungary broke apart, and a new South Slav state was formed, called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later renamed Yugoslavia in 1929). In late 1918, Andrić went back to the University of Zagreb. He became ill again in January 1919. His friends helped him get treatment. In February, he asked his old teacher Tugomir Alaupović, who was now a government minister, for a job in Belgrade. Andrić chose to get treatment in Split for six months, where he almost fully recovered. He also finished another book of prose poetry called Nemiri, which was published the next year.

Starting a Diplomatic Career

By 1919, Andrić had finished his degree in South Slavic history and literature. He was very poor and struggled to support himself and his family. In September 1919, Alaupović offered him a secretarial job at the Ministry of Religion, which Andrić accepted.

In late October, Andrić moved to Belgrade. He became well-known in the city's literary groups but preferred to stay private. He wasn't happy with his government job and asked to be transferred to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In February 1920, his request was granted, and he was sent to the Vatican.

Andrić published his first short story, Put Alije Đerzeleza (The Journey of Alija Đerzeleza), around this time. He found diplomatic work demanding and didn't have much time to write. He also started writing in the Ekavian dialect, which is used in Serbia, instead of the Ijekavian dialect from Bosnia. He soon asked for another transfer and was sent to Bucharest in November. His health got worse, but his duties were light, so he focused on writing. In 1922, he moved to the consulate in Trieste, but the damp climate made him sicker. In January 1923, he transferred to Graz, Austria, where he became vice-consul. He also enrolled at the University of Graz and began working on his PhD in Slavic studies.

Moving Up in His Career

In August 1923, a new law required all civil servants to have a doctoral degree. Since Andrić hadn't finished his, his job was at risk. However, his friends helped him, and the Foreign Ministry kept him on as a day worker. This gave him time to finish his PhD. In May 1924, he submitted his dissertation, The Development of Spiritual Life in Bosnia Under the Influence of Turkish Rule, and received his PhD in July. In his dissertation, he described the Ottoman rule as a heavy burden on Bosnia.

After getting his PhD, Andrić was reinstated at the Foreign Ministry. He stayed in Graz until October, then moved to Belgrade. For two years in Belgrade, he spent a lot of time writing. His first collection of short stories was published in 1924, and he received an award from the Serbian Royal Academy. In October 1926, he was sent to Marseille as vice-consul, and then to the Yugoslav embassy in Paris in December.

Andrić felt lonely in France. His uncle, mother, and aunt had all passed away. He wrote to a friend, "Apart from official contacts, I have no company whatever." He spent much of his time in Paris archives, researching French reports about Travnik, which he later used for his novel Travnička hronika.

In April 1928, Andrić was sent to Madrid as vice-consul. There, he wrote essays and started working on his novel Prokleta avlija (The Damned Yard). In June 1929, he became secretary of the Yugoslav legation in Brussels. In 1930, he joined Yugoslavia's team at the League of Nations in Geneva. In 1933, Andrić returned to Belgrade. Two years later, he became head of the political department at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In 1937, he became an assistant to Milan Stojadinović, Yugoslavia's Prime Minister. That year, France gave him the Legion of Honour award.

World War II and Writing

Andrić was appointed Yugoslavia's ambassador to Germany in 1939. This showed how highly his country's leaders thought of him. Yugoslavia had been getting closer to Germany. In March 1941, Yugoslavia signed the Tripartite Pact, agreeing to support Germany and Italy. Even though Andrić was against this, he had to attend the signing in Berlin as ambassador. He tried to delay the agreement as long as possible. On March 17, he asked to be removed from his duties. Ten days later, a group of officers overthrew the government in Yugoslavia, which angered Adolf Hitler and led to Germany invading Yugoslavia.

Before the invasion, the Germans offered Andrić a chance to go to neutral Switzerland, but he refused because his staff couldn't go with him. On April 6, 1941, Germany and its allies invaded Yugoslavia. The country surrendered on April 17 and was divided. In early June, Andrić and his staff were taken back to German-occupied Belgrade. Andrić retired from the diplomatic service and refused to work with the puppet government set up by the Germans. He was not jailed, but the Germans watched him closely. Because he was Croat, they offered him a chance to live in Zagreb, the capital of a fascist state, but he said no.

Andrić spent the next three years living quietly in a friend's apartment in Belgrade. During this time, he focused on writing and completed two of his most famous novels: The Bridge on the Drina and Travnička hronika. In October 1944, the Red Army and the Partisans drove the Germans out of Belgrade, and Tito became Yugoslavia's leader.

Later Life and Achievements

Public Life and Marriage

After the Germans left Belgrade, Andrić slowly returned to public life. His novel The Bridge on the Drina was published in March 1945. It was followed by Travnička hronika in September and Gospođica in November. The Bridge on the Drina became known as his greatest work and a classic of Yugoslav literature. It tells the story of the Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge and the town of Višegrad from the 16th century until World War I. Travnička hronika is about a French diplomat in Bosnia during the Napoleonic Wars. Gospođica is about a woman from Sarajevo. Andrić also published short story collections and essays.

In November 1946, Andrić became vice-president of the Society for Cultural Cooperation with the Soviet Union. He was also named president of the Yugoslav Writers' Union. The next year, he became a member of the People's Assembly of Bosnia and Herzegovina. In April 1950, Andrić became a deputy in the National Assembly of Yugoslavia. He received an award in 1952 for his service to the Yugoslav people. In 1954, he published the novella Prokleta avlija (The Damned Yard), which describes life in an Ottoman prison. That December, he joined the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, the ruling party.

On September 27, 1958, the 66-year-old Andrić married Milica Babić, a costume designer who was almost twenty years younger than him. He had once said it was "probably better" for a writer never to marry.

Nobel Prize and Final Years

By the late 1950s, Andrić's books were being translated into many languages. In 1958, the Association of Writers of Yugoslavia nominated him for the Nobel Prize in Literature. On October 26, 1961, he was awarded the Nobel Prize by the Swedish Academy. The Nobel Committee praised how he "traced themes and depicted human destinies drawn from his country's history."

When the news was announced, reporters crowded Andrić's apartment in Belgrade. He publicly thanked the Nobel Committee. Andrić donated all of his prize money, about 30 million Yugoslav dinars, to buy library books in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The Nobel Prize made Andrić famous around the world. He received many more awards, including the Order of the Republic in 1962 and the Order of the Hero of Socialist Labour in 1972. He was also a member of several academies of sciences and arts and received honorary doctorates from universities.

Andrić's wife passed away on March 16, 1968. His health slowly got worse, and he traveled less in his final years. He continued to write until 1974. In December 1974, he was admitted to a Belgrade hospital. He fell into a coma and died on March 13, 1975, at the age of 82. His body was cremated, and his ashes were buried in Belgrade's New Cemetery on April 24. About 10,000 people attended the ceremony.

His Writing Style and Themes

Andrić loved to read when he was young. He read many different kinds of books, from ancient Greek and Latin works to writers from Germany, France, Britain, Spain, Italy, Russia, Norway, and America. He especially liked Polish literature and said it influenced him a lot. He also admired several Serb and Slovene writers. The philosopher Søren Kierkegaard strongly influenced his ideas.

Much of Andrić's work was inspired by the traditions and unique life in Bosnia. He explored the complex mix of cultures among Muslims, Serbs, and Croats in the region. His two most famous novels, The Bridge on the Drina and Travnička hronika, show the difference between Bosnia's "oriental" (Eastern) ways from Ottoman times and the "Western atmosphere" brought by the French and later the Austro-Hungarians. His books use many words from Turkish, Arabic, or Persian that became part of the South Slav languages during Ottoman rule.

Many scholars believe that the bridge in The Bridge on the Drina represents Yugoslavia itself, which was a "bridge" between East and West during the Cold War. In his Nobel acceptance speech, Andrić described Yugoslavia as a country trying to catch up in culture and other areas after a difficult past. Andrić believed that understanding history could help future generations avoid past mistakes. He hoped that the differences between Yugoslavia's ethnic groups could be overcome.

Andrić's Legacy

Before he died, Andrić said he wanted all his belongings to be used to create an endowment for "general cultural and humanitarian purposes." In March 1976, a committee decided that the endowment would promote the study of Andrić's work, as well as art and literature. The Ivo Andrić Endowment has organized many international conferences and given grants to scholars studying his works. They also publish an annual journal. Andrić's will stated that an award should be given each year to the author of the best collection of short stories.

The street next to Belgrade's New Palace, where the President of Serbia works, was named Andrićev venac (Andrić's Crescent) in his honor. It has a life-sized statue of him. The apartment where Andrić spent his final years has been turned into a museum. It opened a year after his death and holds his books, writings, documents, photos, and personal items.

Andrić is still the only writer from former Yugoslavia to win the Nobel Prize. Because he used the Ekavian dialect and wrote most of his novels in Belgrade, his works are mostly connected with Serbian literature. Many people in Bosnia and Croatia have different views on his connection to their literatures. After Yugoslavia broke up in the early 1990s, his works were even banned in Croatia for a while, but they were later brought back by writers and scholars.

Some Bosniak scholars have criticized Andrić's portrayal of Muslim characters in his books. In the 1950s, some even called for his Nobel Prize to be taken away. In 1992, a Bosniak nationalist in Višegrad destroyed a statue of Andrić. However, in 2012, filmmaker Emir Kusturica and Bosnian Serb President Milorad Dodik unveiled another statue of Andrić in Višegrad as part of the new town called Andrićgrad.

Since the early 1990s, Andrić's picture has appeared on Yugoslav dinar banknotes. His image is also on some banknotes in Bosnia and Herzegovina and on Serbian dinar coins minted in 2011 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of his Nobel Prize.

Works

Source:

Novels

- 1945 Na Drini ćuprija.

- 1945 Travnička hronika.

Novellas

- 1920 Put Alije Đerzeleza.

- 1945 Gospođica.

- 1948 Priča o vezirovom slonu.

- 1954 Devil's Yard (Prokleta avlija).

Short Story Collections

- 1924 Pripovetke I.

- 1931 Pripovetke.

- 1936 Pripovetke II.

- 1945 Izabrane pripovetke.

- 1947 Most na Žepi: Pripovetke.

- 1947 Pripovijetke.

- 1948 Nove pripovetke.

- 1949 "Priča o kmetu Simanu". (short story)

- 1952 Pod gradićem: Pripovetke o životu bosanskog sela.

- 1958 "Panorama". (short story)

- 1960 Priča o vezirovom slonu, i druge pripovetke.

- 1966 Ljubav u kasabi: Pripovetke.

- 1968 Aska i vuk: Pripovetke.

Poetry

- 1918 Ex Ponto.

- 1920 Nemiri.

Nonfiction

- 1976 Eseji i kritike. (essays; published after his death)

- 2000 Pisma (1912–1973): Privatna pošta. (private letters; published after his death)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Ivo Andrić para niños

In Spanish: Ivo Andrić para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |