James Cropper (abolitionist) facts for kids

James Cropper (1773–1840) was an English businessman and philanthropist, which means he was a kind person who helped others. He was also a strong abolitionist, someone who worked to end slavery. James Cropper played a huge part in ending slavery across the British Empire in 1833.

Contents

- Early Life and Business Beginnings

- Leading the Fight to End Slavery

- Supporting Black Activists in the United States

- Inspiring James McCune Smith

- Working with William Lloyd Garrison

- Ending the Apprenticeship Scheme

- Other Achievements

- Death and Tributes

- The 'Liverpool Dingle Group' Legacy

- Modern Views on Liverpool's Anti-Slavery Role

- Publications by James Cropper

Early Life and Business Beginnings

James Cropper was born in Winstanley, Lancashire, into a Quaker family. Quakers are a religious group known for their strong beliefs in equality and peace. His father wanted him to work on the family farm, but James left home at 17. He became an apprentice at a trading company in Liverpool called Rathbone Brothers.

In 1796, James Cropper married Mary Brinsmead. They had two sons, John and Edward, and a daughter. In 1799, James started his own shipping company, Cropper, Benson and Co., with Thomas Benson. His business success allowed him to build a beautiful home called Dingle Bank in Liverpool, overlooking the River Mersey. He also built two houses nearby for his sons.

James Cropper became very active against slavery in the Caribbean. He also cared deeply about poverty in Ireland, visiting often and even setting up cotton mills there.

Leading the Fight to End Slavery

The Cropper family were Quakers, and their faith strongly believed in ending the slave trade. In 1790, James Cropper joined Rathbone, Benson and Co., where the owner, William Rathbone, was a leading abolitionist. Young James soon met other anti-slavery activists in Liverpool. This was important because Liverpool was a city deeply involved in the slave trade.

After the Slave Trade Act of 1807, which banned the trade of slaves but didn't free anyone, James Cropper joined the African Institution. He realized that slavery wouldn't just "die out." Historians like Joshua Civin say that James Cropper and other Liverpool merchants were key to making the British anti-slavery movement strong again.

Starting the Emancipation Campaign

James Cropper was worried about how enslaved Africans were still being treated after 1807. Michael R Watts, in his book The Dissenters (1978), says that Cropper started the campaign to free all enslaved people.

He began by writing letters to William Wilberforce, a famous abolitionist, in 1821. These letters were published in the Liverpool Mercury newspaper. Cropper argued that slavery was becoming less profitable and was only kept alive by unfair financial support. He compared it to sugar grown by free people in the East Indies.

Mark Jones, in his 1998 study, also states that James Cropper started the anti-slavery movement that led to the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act. This act finally ended slavery across the British Empire.

Historians say that James Cropper pushed the movement forward. The older abolitionists joined him only after he had set a new direction for the cause.

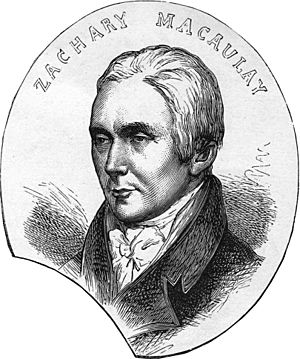

Working with Zachary Macaulay

Cropper also reached out to another experienced abolitionist, Zachary Macaulay, who used to be the Governor of Sierra Leone. In a letter from July 1822, James Cropper shared his plan to create a society in Liverpool. This society would work to completely abolish slavery.

Macaulay had personal experience working on plantations in the West Indies. He saw firsthand the terrible effects of the slave trade. He also had an amazing memory and provided facts and figures for many anti-slavery speeches in Parliament.

Macaulay's daughter, Margaret, later married James Cropper's son, Edward. This created a strong group of abolitionists called the 'Dingle Group,' centered around James Cropper's home. Cropper used his shipping connections in the United States to gather reliable information about the lives of enslaved people. He also promoted the idea that free labor was better than slave labor, to show that slavery was not economically sound.

Recruiting Thomas Clarkson

In June 1823, James Cropper suggested to Zachary Macaulay that Thomas Clarkson should travel across the country again. Clarkson had done this in 1788 to campaign against the slave trade. This time, he would campaign for the total end of slavery.

Cropper wrote the letter from Clarkson's own home. He then gave Clarkson £500 (about £65,000 in today's money) to pay for his tour of the United Kingdom. Cropper's sons, John and Edward, each gave an extra £100.

Cropper's bold ideas for Clarkson's tour might have caused some disagreement with William Wilberforce, who had more moderate views. However, in October 1824, Wilberforce sent a letter saying he fully supported Cropper's new campaign to free enslaved people. Wilberforce wrote, "Good Cropper's proposal... makes me love better, a man I already esteemed and loved."

Clarkson and Cropper divided the country between them. Cropper and others visited areas that already had anti-slavery groups. Clarkson used his powerful speaking skills to convince new audiences to join the cause. Clarkson remained a key speaker and worked closely with Cropper to send anti-slavery materials to the United States.

Bringing in Joseph Sturge

Cropper didn't just work with older abolitionists. He also brought in new, younger people, like Joseph Sturge from Birmingham. Cropper personally guided Sturge to become a strong abolitionist. In October 1825, Joseph Sturge joined James Cropper, who was promoting the anti-slavery cause in central England.

Cropper and Sturge spoke with important citizens, held public meetings, gave speeches, and formed new societies. Both shared similar Quaker backgrounds. Cropper was impressed by Sturge's speeches at anti-slavery meetings in London in 1823 and 1824. Despite a 20-year age difference, they became a powerful team and lifelong friends.

In 1831, Joseph Sturge partnered with James Cropper's son, John Cropper. They formed the Young England Abolitionists. This group was known for its strong arguments and energetic campaigning. Joseph Sturge later married James Cropper's daughter, Eliza. This further strengthened the 'Dingle Group' of abolitionists, which was the extended Cropper family.

Recruiting Daniel O'Connell

In 1824, Cropper and his daughter Eliza visited Ireland. He saw many farmers who were very poor and struggling to find work. During this visit, James Cropper recruited one of the best anti-slavery speakers of the 1800s, Daniel O'Connell.

Historian Patrick M. Geoghegan notes that O'Connell's interest in slavery began in 1824 when James Cropper visited Ireland. Cropper wanted to gain support for his plan to weaken slavery in the West Indies.

O'Connell's connection with the 'Dingle Group' grew even stronger. In 1844, Edward Cropper's father-in-law, Lord Denman, who was a top judge, helped O'Connell get out of prison early. O'Connell had been jailed for encouraging rebellion in Ireland. O'Connell later inspired many important Black activists, including Frederick Douglass, a famous African American speaker. Douglass said of O'Connell, "I feel grateful to him, for his voice has made American slavery shake to its centre."

Supporting Black Activists in the United States

In the 1820s, James Cropper supported several initiatives for free Black people in America. For example, in 1828, he gave money to a school for Black infants in Philadelphia. He also provided a lot of financial help for American anti-slavery newspapers.

James Cropper used his connections in Liverpool to directly encourage anti-slavery work in the United States. Sir John Gladstone, a supporter of slavery, was worried about Cropper's growing influence. He wrote that "Considerable alarm has been felt in the southern states since Mr Cropper's publications have been circulated amongst the slaves there."

The Cropper family kept a scrapbook full of anti-slavery writings. It included a list of contacts in the United States who had received large packages of his anti-slavery pamphlets from Liverpool. These pamphlets, often 20 pages long, were read aloud at meetings and found their way to the slave states. Early lists (around 1827-1829) included the editors of all three American anti-slavery newspapers.

Benjamin Lundy, a fellow Quaker, edited the Genius of Universal Emancipation and often thanked his sponsors in Liverpool. John Brown Russwurm edited the first Black newspaper, Freedom's Journal (1827-1829). Russwurm was one of the first African Americans to graduate from an American college. Quaker Enoch Lewis edited the African Observer (1827-1828). Cropper later worked with Peter Williams, Jr., an African American bishop, as his main contact in New York's free Black community. Williams later joined the American Antislavery Society. Cropper also sent pamphlets to William Lloyd Garrison. Cropper's list from the 1830s included James McCune Smith, a young Black intellectual and activist. Smith was the first African American to earn a medical degree, which he received in Glasgow, Scotland.

Cropper's pamphlet activities also had an effect in New York City. The local free Black community noticed them. In December 1832, Black people in New York City formed their own anti-slavery society. They thanked European supporters like James Cropper and Thomas Cropper from England, and Daniel O'Connell from Ireland. They praised them as friends of Black rights and religious freedom.

Inspiring James McCune Smith

On September 9, 1832, James McCune Smith, a 19-year-old Black activist and scholar, arrived in Liverpool. He spent almost a week in the city. On September 11, 1832, Smith visited James Cropper at Dingle Bank. Cropper's strong dedication to the anti-slavery cause deeply impressed James McCune Smith.

Smith wrote about his visit: "Chartered a coach, and drove out to the Princely mansion of J.C. Esq., which is beautifully situated in a lovely spot, on the banks of the Mersey... The tone of conversation delighted me. All appeared familiar with the names of our leading abolitionists... What chiefly affected me, was to perceive on several articles of the breakfast set, the figure of a chained and kneeling slave – under which was written 'Remember them that are in bonds, as being bound with them... How deeply must he feel for the sufferings of bondsmen, who makes such remembrances the companions of his meals!'"

At an anti-slavery debate in Liverpool, James Cropper also introduced McCune Smith to George Thompson, a strong abolitionist from Liverpool. McCune Smith was thrilled to meet him.

The Work of James McCune Smith

George Thompson (1804–1878) was a famous activist and anti-slavery speaker in both Britain and America. He later became a Member of Parliament in London. Thompson's first speaking tour of the United States in 1834 was at the invitation of his friend William Lloyd Garrison. Thompson's fierce speeches against slavery often led to death threats. Thompson was also a lifelong friend of the Black abolitionist Nathaniel Paul. All these activists had strong connections to James Cropper at Dingle Bank.

In 1853, James McCune Smith, along with his close friend Frederick Douglass, helped start the National Council of Colored People. This was the first lasting national organization for African Americans. Frederick Douglass called McCune Smith "the single most important influence on my life." Smith wrote the introduction to Douglass's book My Bondage and My Freedom in 1855.

Working with William Lloyd Garrison

In 1833, the American abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison was invited to Dingle Bank. The success of his speaking trip depended a lot on Cropper's help. Garrison arrived in Liverpool in 1833, just as the Abolition of Slavery Act was being discussed in Parliament. Garrison would become the leading American abolitionist before the American Civil War.

Garrison stayed at Dingle Bank for three days before going to London. When he arrived in Liverpool in May 1833, Garrison wrote that James Cropper had a "delightful retreat" called Dingle Bank. He felt very welcomed.

Garrison also said that James Cropper convinced William Wilberforce to stop supporting the American Colonization Society. This group wanted to send Black people back to Liberia, a free African state. Cropper had previously written a pamphlet criticizing his friend Thomas Clarkson for supporting this society.

Ending the Apprenticeship Scheme

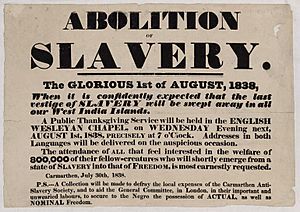

In 1833, slavery in the Caribbean was replaced by a six-year 'apprenticeship' scheme. James Cropper suspected that this scheme was not much better than slavery. In 1836, his son-in-law Joseph Sturge was sent to Jamaica to report on the conditions on the plantations.

Historian K. Charlton (1971) states that Joseph Sturge, with Cropper's constant support, fought the final battle against the apprenticeship system. Joseph Sturge traveled to the Caribbean, and his report to Parliament led to the apprenticeship scheme being ended two years early. This brought true freedom to 800,000 enslaved people on August 1, 1838.

Other Achievements

James Cropper was a successful businessman. He founded Cropper, Benson, & Co., and earned a large fortune. He worked to remove trade restrictions with the United States. He also became involved with the port of Liverpool.

From 1830, Cropper was an active director of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. In 1833, he decided to start an industrial school for boys, focusing on farming. After visiting Germany and Switzerland, he built a school and orphan-house on his estate near Warrington.

Death and Tributes

James Cropper lived at Fearnhead until his death in February 1840. He was buried in the Quaker burial-ground in Liverpool next to his wife.

After James Cropper died, William Lloyd Garrison, the editor of the American anti-slavery newspaper The Liberator, wrote a poem in his honor. Garrison's poem praised Cropper as wise, great, and good, and said his memory would be honored forever.

Harriet Beecher Stowe's Tribute

In 1853, the famous American author Harriet Beecher Stowe visited Liverpool. This was the start of her speaking tour across major British cities. Stowe's famous book, Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852), showed the harsh realities of slavery in the United States. The book sold over 300,000 copies in the U.S. and more than 1.5 million in the UK. It was the best-selling novel of the 19th century.

In her memoirs, Sunny Memories of Foreign Lands (1854), Stowe wrote about James Cropper and his family. She saw them as the ones who started the 'abolitionist revival' that led to the 1833 Act and the freeing of 800,000 people.

Stowe wrote that Liverpool was like New York in America, where business interests were tied to the slave trade. She noted that the opposition to early anti-slavery activists in Liverpool was as strong as it was in Charleston, a city deeply involved in slavery.

On April 13, 1853, Harriet Beecher Stowe gave a public speech in Liverpool. The chairman, Mr. Adam Hodgson, presented her with a petition signed by 21,953 women of Liverpool supporting her cause. Stowe thanked the people of Liverpool for their warm welcome. She said she felt at home and saw only friendly faces.

Harriet Beecher Stowe again praised James Cropper and his family for starting the 'abolitionist revival.' This movement led to the complete end of slavery in the British Empire in 1833.

The 'Liverpool Dingle Group' Legacy

James Cropper died just a few months before the first World Anti-Slavery Convention was held in London in 1840. His son, John Cropper, attended with his brother-in-law and event organizer, Joseph Sturge. By organizing this convention, Joseph Sturge and the 'Dingle Group' finally brought together major British and American abolitionists.

Historian William Caleb McDaniel (2006) noted that American abolitionists knew the names of famous British abolitionists like Clarkson, Cropper, and Wilberforce. The World's Convention allowed many American abolitionists to meet British reformers in person.

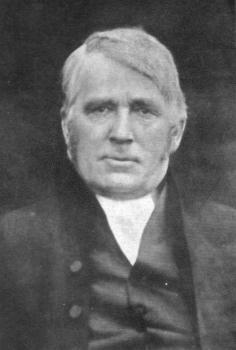

John Cropper (1797-1874)

John Cropper, James's son, welcomed Harriet Beecher Stowe to Dingle Vale several times. He was known as "the most generous man in Liverpool." John Cropper is mentioned in Edward Lear's poem "He Lived at Dingle Bank" and in Elizabeth Gaskell's novel Mary Barton (1849). It's also believed that the sandy bay near Dingle Bank inspired a location in Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Island. John Cropper had given £100 (about £13,000 today) to support Thomas Clarkson's anti-slavery tour in 1823.

Edward Cropper (1799-1877)

Edward Cropper, James's other son, was also a dedicated abolitionist. He also gave £100 to support Thomas Clarkson's tour in 1823. As Quakers, the Croppers often married into families who shared their religious beliefs and commitment to ending slavery. Edward's marriages helped to expand the influence of the 'Dingle Group' of abolitionists.

Eliza Cropper (1800-1835)

Eliza Cropper, James's daughter, was a key member of the Liverpool Ladies' Anti-Slavery Association, founded in 1827. She supported her father's anti-slavery work. According to Joshua Civin (2001), James Cropper couldn't have had such influence without the help of the women in his household. Eliza sent pamphlets to William Lloyd Garrison and others in the United States. She also helped create a network of British and American women who fought against slavery and for women's rights.

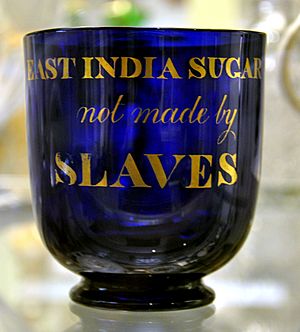

Eliza Cropper was crucial to the boycott of slave-grown products. She made up packages of sugar and coffee grown by free labor in the East Indies. These packages were then given to Members of Parliament. In April 1834, Eliza Cropper married the abolitionist Joseph Sturge. Sadly, she died in childbirth on February 18, 1835, and the baby was also lost.

Margaret Macaulay Cropper (1812–1834)

Margaret Macaulay Cropper was the daughter of abolitionist Zachary Macaulay. She was also the sister of the famous historian and politician 1st Baron Macaulay. Margaret was Edward Cropper's second wife and died at age 22 in 1834.

Margaret Denman Cropper (1815–1899)

Margaret Denman Cropper, Edward Cropper's third wife, welcomed author Harriet Beecher Stowe during her visits to Dingle Bank. Margaret corresponded with author Charles Dickens about her father, Lord Denman, supporting Harriet Beecher Stowe's novel Uncle Tom's Cabin. She also wrote to Frederick Douglass, a freed American slave and speaker. She sent him gifts, including the book Dr Livingstone's Travels and a scarf for his wife. Douglass thanked Margaret Cropper for money donated by the Liverpool Anti-slavery Society, where Margaret Cropper was president.

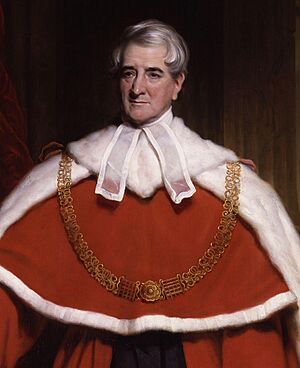

Lord Thomas Denman (1779-1854)

Lord Thomas Denman was an abolitionist politician and Queen Victoria's first Lord Chief Justice. He corresponded with Harriet Beecher Stowe as early as 1836. Denman's daughter Margaret was married to Edward Cropper. In Parliament, Denman had proposed ending slavery as early as 1826.

Denman's pamphlet, Uncle Tom's Cabin, Bleak House, Slavery and the Slave Trade, helped make Harriet Beecher Stowe's novel Uncle Tom's Cabin the best-selling book of the 19th century. It's even said that Abraham Lincoln believed this book helped start the American Civil War.

After praising Uncle Tom's Cabin, Lord Denman hoped the novel would "Urge abolition as a paramount duty to God." Harriet Beecher Stowe also paid tribute to Denman, noting his efforts despite his poor health. She also commented on his strong family ties with Dingle Bank.

Rear Admiral Joseph Denman (1810–1874)

Rear Admiral Joseph Denman was Lord Denman's son and Margaret Denman Cropper's brother. He was also Edward Cropper's brother-in-law. Denman was a Commander in the West Africa Squadron, a Royal Navy group set up to stop slave ships off the west coast of Africa.

In 1839, Denman's ship, HMS Wanderer, captured five slave ships in six months, freeing their captives. Spanish and Portuguese slave traders were still active. In November 1840, Governor Doherty of Sierra Leone ordered Captain Joseph Denman to rescue two British subjects held hostage. Denman took three British warships and 120 men. He led a strong campaign along the African coast, burning down 'slave factories' (places where enslaved people were held).

After freeing the hostages, Captain Denman forced King Siaka to sign a treaty ending slavery in the Gallinas region. Denman destroyed eight slave factories, freed 841 enslaved people, and made sure all slave traders left the Gallinas Kingdom. One of the destroyed factories was at Lomboko, which is shown in the Stephen Spielberg film Amistad.

Denman's actions almost ended his naval career. He was sued by a slave trader for damages. The case, Buron vs Denman, was heard in 1848, and the court sided with Denman. While waiting for trial, Denman wrote detailed instructions for stopping the 'Middle Passage' (the journey of enslaved people from Africa to the Americas). Denman's plan became government policy in 1844.

The Royal Navy was encouraged to destroy any slave factory and stop any suspected slave ship. These new powers led to a sudden and large drop in slave ship numbers in the late 1840s and 1850s. By the time the American Civil War began in 1861, the 'Middle Passage' and the slave trade had mostly ended on the West African coast. Joseph Denman ended his career as an admiral. He was a favorite of Queen Victoria and commanded her royal yacht. He died on November 26, 1874.

Modern Views on Liverpool's Anti-Slavery Role

Some modern experts have a different view of how much James Cropper, the Dingle Group, and Liverpool helped end slavery in 1833. They often focus on the 1807 Act, which didn't free anyone, rather than the more important 1833 Act, which was largely started in Liverpool.

For example, the National Museums Liverpool website states that Harriet Beecher Stowe's liberal views "were not well received" during her 1853 visit. This is different from Harriet Beecher Stowe's own published diary, where she described a warm welcome.

Some historians also say that Liverpool had only a "very small showing of abolition culture." They claim there were not many public anti-slavery campaigns compared to other towns. The Head of the International Slavery Museum in Liverpool, Paul Reid, said, "Liverpool didn't just take part, but also resisted abolition. It's a fascinating and difficult history."

Publications by James Cropper

James Cropper published many pamphlets about the conditions in the West Indies and about sugar taxes. His main publications, all released in Liverpool, include:

- Letters to William Wilberforce, M.P., recommending the cultivation of sugar in our dominions in the East Indies, 1822. This argued against taxes on sugar from the East Indies that helped slave owners in the West Indies.

- The Correspondence between John Gladstone, Esq., M.P., and James Cropper, Esq., on the present state of slavery, 1824.

- Present State of Ireland, 1825, in the Quarterly Christian Spectator.

|

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |