Japanese Internment at Ellis Island facts for kids

During World War II, many Japanese-Americans living on the East Coast of the United States were held in a special camp. This camp was located on Ellis Island. This event is known as the Japanese internment at Ellis Island.

A big reason for this was New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia ordering Japanese-Americans to be arrested. Later, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066. This order started the mass internment of Japanese-Americans across the entire United States.

Other things also led to this internment. For example, the Niʻihau Incident made many people fear that Japanese residents were not loyal to the U.S. There was also a concern that Japanese-Americans might be spies. This was especially worrying for the U.S. efforts to break secret codes. Many people later questioned if this internment was fair in the Supreme Court.

Contents

Why Japanese Internment Happened

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt declared war on December 8, 1941. This was one day after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Soon after, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia ordered Japanese nationals to be gathered. They were sent to Ellis Island for an unknown time.

LaGuardia’s order happened before Executive Order 9066. President Roosevelt issued this order on February 19, 1942. It led to about 110,000 American citizens of Japanese descent being interned across the U.S. Just 24 hours after Pearl Harbor, 121 Japanese New Yorkers were arrested. By mid-December, this number grew to 279 Japanese-American New York residents.

The Niʻihau Incident

The Niʻihau incident happened from December 7–13, 1941. This was right after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Niʻihau is a Hawaiian island. The Japanese Navy thought it was empty and planned to use it for damaged planes.

But native Niʻihauans and the Robinson family lived there. The island was closed to outsiders. A pilot named Shigenori Nishikaichi crash-landed on Niʻihau. The residents helped him. He shared details about the Pearl Harbor bombing with them. When they realized how serious it was, authorities caught Nishikaichi.

The pilot got help from some residents of Japanese descent. He then got away from his captors. Nishikaichi got weapons and took several people hostage. Later, Niʻihauans Benehakaka Kanahele and his wife Kealoha Kanahele killed him. Authorities used this event to suggest that Japanese-Americans could be a threat to the U.S. war effort.

Code-Breaking Concerns

David Lowerman, who worked for the NSA, worried about U.S. code-breaking efforts. He thought Japanese-Americans might intercept them. He called this a "frightening specter of massive espionage nets." However, there was very little proof of a Japanese-American spy system.

No Japanese-American living in the U.S. was found guilty of serious spying or sabotage during WWII. But this did not stop the government from seeing them as a threat. Because of this, Lowerman decided that holding them would keep U.S. code-breaking efforts secret. These efforts gave the U.S. a big advantage over the Japanese Imperial Navy. If their codes were found out, the Japanese Navy would change them. This would stop the U.S. from reading their messages.

Feelings of Nationalism

Some people believe Executive Order 9066 came from anti-immigrant feelings. These feelings were common in the early 1900s. Nativism is a belief that favors people born in a country over immigrants. During World War II, anyone with ties to another country was sometimes seen as a traitor. This was true even if they were U.S. citizens.

The Alien Registration Act shows that nationalism was already present before Pearl Harbor. This law required all non-citizens aged 14 and older to register with the government. This list was later used to decide which Japanese-Americans would be sent to Ellis Island.

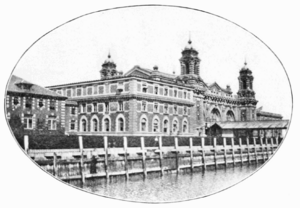

Ellis Island During World War II

During World War II, Ellis Island had many different uses. Immigration processing there dropped by 97%. It still served as a place to deport and hold people. But its buildings were also used by the U.S. military. They held prisoners-of-war and "enemies of the state" there.

These "enemies of the state" included about 7,000 people of Italian, German, and Japanese descent. Ellis Island also became a hospital for soldiers returning from war. It was a training ground for the U.S. Coast Guard. And it hosted the crews of captured enemy ships.

Japanese Experience on Ellis Island

Being Interned

Before the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the U.S. Justice Department had a plan. They wanted to gather foreigners because of tensions from World War I. Letters from the Attorney General's office show this. They gave instructions to arrest 600 people from New York and 200 from New Jersey each month. These people were to be held at Ellis Island.

This process began the day after Pearl Harbor, on December 8, 1941.

Many of the arrested people were later released. Others were held in internment. This often happened because their hearings were before a local "alien enemy hearing board." This was the case for many Japanese-American leaders held on Ellis Island. Few of the people interned actually supported the enemy. Most were held based on weak evidence or unproven accusations.

Conditions at the Camp

The time Japanese-Americans spent interned on Ellis Island varied. Some stayed up to two years. Others were quickly moved to different detention centers. One Japanese-American, Naoye Suzuki, was thought to be a spy. Suzuki was arrested and taken to Ellis Island for over a year.

He learned that citizens could not be held as "enemy aliens." Suzuki then argued for his freedom because he was born in the United States. His argument worked, and Suzuki left Ellis Island in the spring of 1943.

The long stays were hard for many internees at Ellis Island. The facility had only housed people for short times before. The island was seen as a perfect prison. It had large dining rooms and good dormitories. When they arrived, the "enemy aliens" stayed in the Main Immigration Building.

The Registry Room was used as a family area for Japanese-Americans, as well as Italian and German "enemy aliens." More space was made in 1943. This happened when administrative workers moved to an office in New York. This freed up dormitory space for the people being held there.

After being arrested, prisoners were given U.S. army shoes, khaki socks, a shirt, and underwear. Some prisoners described the conditions as "bad food, bad medical care, overcrowding, lack of exercise and unhealthy conditions, including rats." Japanese-American internees also seemed to eat in the same room as the Italian and German "enemy aliens."

After the War Ended

The internment of Japanese "enemy aliens" at Ellis Island changed how people thought about the island. The New York Times reported that "the Island’s name had become a symbol for being unwanted by America." 1945 brought the end of World War II. The camp at Ellis Island closed completely later that year.

Some internees stayed for one to four months. Others, like Suzuki, stayed for a year. By February 1944, only three Japanese-Americans were held at Ellis Island. By June 1944, that number dropped to one. The United States, under President Jimmy Carter, later apologized to Japanese-Americans for the internment. A study found that the internment had not been necessary or justified for military reasons.

Supreme Court Cases About Internment

Several cases went to the Supreme Court about the government's power to hold citizens during wartime. The first of these was Ozawa v. United States (1922). In this case, Takao Ozawa was not allowed to become a U.S. citizen. The Naturalization Act of 1906 said that any "free white person" or "person of African descent" could become a citizen. Ozawa argued he should be seen as a "free white person" and allowed to become a citizen. He lost the case and was denied citizenship. This case ruled that Japanese people were not fit to become Americans. It was used in later court cases to justify internment.

Yasui v. United States (1943) questioned if it was fair to make U.S. citizens follow a curfew. When Executive Order 4066 was put in place, all Japanese-Americans had to follow a curfew and eventually move. The Supreme Court found that a curfew for citizens during wartime was fair.

Minoru Yasui challenged this decision. He said a curfew was not fair. The Supreme Court ruled that a curfew for citizens in normal times was not fair. But under Order 4066, Yasui had lost his citizenship by working for the Japanese consulate. So, he was subject to the curfew.