Fred Korematsu facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Fred Korematsu

是松豊三郎 |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu

January 30, 1919 Oakland, California, U.S.

|

| Died | March 30, 2005 (aged 86) Marin County, California, U.S.

|

| Resting place | Mountain View Cemetery |

| Monuments |

|

| Alma mater | Castlemont High School |

| Known for | Korematsu v. United States |

| Spouse(s) |

Kathryn Pearson

(m. 1946) |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards | Presidential Medal of Freedom (1998) |

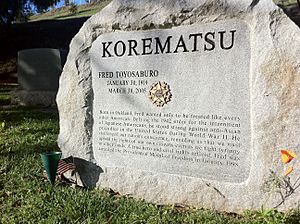

Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu (是松豊三郎, Korematsu Toyosaburo, January 30, 1919 – March 30, 2005) was an American civil rights activist. He stood up against the unfair treatment of Japanese Americans during World War II. His brave actions led to a famous court case that is still talked about today.

Contents

Early Life and Challenges

Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu was born in Oakland, California, on January 30, 1919. He was the third of four sons. His parents, Kakusaburo Korematsu and Kotsui Aoki, were Japanese immigrants. Fred played tennis for his school team at Castlemont High School. He also worked at his family's flower nursery in San Leandro, California.

World War II and Unfair Treatment

When World War II began, Fred wanted to serve his country. He was called for military duty but was rejected by the U.S. Navy because of stomach ulcers. He then trained to become a welder to help with the war effort.

Fred found a job as a welder at a shipyard. One day, his timecard was missing. His coworkers quickly told him he couldn't work there because he was Japanese. He found another job, but was fired after a week. This happened because of his Japanese background. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Fred lost all his jobs.

On March 27, 1942, a general ordered that Japanese Americans could not leave certain areas. This was to prepare for their forced move to internment camps. Fred tried to change his appearance and name to avoid this order. He changed his name to Clyde Sarah and claimed to be of Spanish and Hawaiian heritage.

On May 3, 1942, General DeWitt ordered Japanese Americans to report to special centers. From there, they would be sent to internment camps. Fred refused to go and went into hiding in Oakland. He was arrested on May 30, 1942, in San Leandro. He was held in a jail in San Francisco.

Soon after his arrest, a lawyer named Ernest Besig asked Fred to let his case be used to challenge the unfair internment. Fred agreed because he believed "people should have a fair trial."

Fighting for Justice

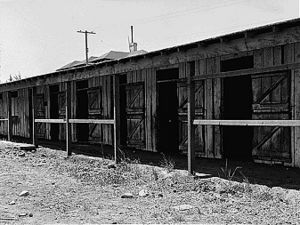

On September 8, 1942, Fred was found guilty in federal court. He was put on five years of probation. He and his family were then sent to the Topaz War Relocation Center in Topaz, Utah. At the camp, he worked for very little money. He was placed in a horse stall with only one light bulb. He later said that "jail was better than this."

When Fred's family moved to the Topaz camp, other Japanese Americans recognized him. Many felt that if they talked to him, they would also be seen as troublemakers.

Fred appealed his case to the U.S. Court of Appeals. The court upheld the original decision. He appealed again, and his case went to the United States Supreme Court. On December 18, 1944, the Supreme Court decided against Fred. They said that forced exclusion was allowed during times of "emergency and peril."

Life After the Camps

After being released from the camp in Utah, Fred could not move back to the West Coast. He moved to Salt Lake City, Utah, where he continued to face racism. He found a job repairing water tanks. But after three months, he found out he was being paid half of what his white coworkers earned. When he complained, his boss threatened to call the police. Fred then left that job. After this, Fred lost hope and stayed quiet about his experiences for over thirty years.

He moved to Detroit, Michigan, where his younger brother lived. He worked there as a draftsman until 1949. He married Kathryn Pearson in Detroit on October 12, 1946. They returned to Oakland in 1949 to visit his sick mother. They decided to stay after Kathryn became pregnant. Their daughter, Karen, was born in 1950, and their son, Ken, in 1954.

Government Apologies and Compensation

In 1976, President Gerald Ford officially ended the order that led to the internment camps. He also apologized for the internment. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter created a special group to study the internment. This group found that the decisions were made because of "race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership." In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. This law gave $20,000 to each Japanese American who had been interned.

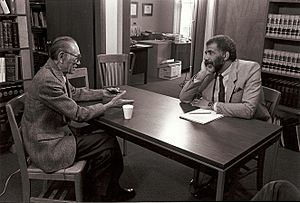

In the early 1980s, a lawyer named Peter Irons and a team led by Dale Minami worked to overturn Fred Korematsu's conviction.

On November 10, 1983, Judge Marilyn Hall Patel of the U.S. District Court in San Francisco officially canceled Fred's conviction. Fred told the judge, "I would like to see the government admit that they were wrong... so this will never happen again to any American citizen of any race, creed, or color." He also said, "If anyone should do any pardoning, I should be the one pardoning the government." Judge Patel's ruling cleared Fred's name, but it could not change the Supreme Court's original decision.

In 1998, Fred Korematsu received the Presidential Medal of Freedom. This is the highest award a civilian can get in the United States.

Fred was a member of the First Presbyterian Church of Oakland. He was also president of the San Leandro Lions Club twice. For 15 years, he volunteered with the Boy Scouts of America.

From 2001 until his death, Fred was part of the Constitution Project's Liberty and Security Committee. In 2004, he warned, "No one should ever be locked away simply because they share the same race, ethnicity, or religion as a spy or terrorist." He added that if this lesson was not learned from the internment, then "these are very dangerous times for our democracy."

Death and Lasting Impact

Fred Korematsu passed away from breathing problems at his daughter's home in Marin County, California, on March 30, 2005. He was buried at the Mountain View Cemetery.

Fred Korematsu's Legacy

The Fred T. Korematsu Institute for Civil Rights and Education continues Fred's work. It helps teachers and community leaders across the country promote justice and civil liberties.

The Fred T. Korematsu Center for Law and Equality at the Seattle University School of Law works to "advance justice and equality."

Many places and awards are named in his honor:

- Fred T. Korematsu Elementary School in Davis, California.

- The auxiliary campus at San Leandro High School is named the Fred T. Korematsu Campus.

- The Discovery Academy elementary school in Oakland, California, was renamed Fred T. Korematsu Discovery Academy.

- Portola Middle School in El Cerrito, California, was renamed The Fred T Korematsu Middle School.

- In 1988, a street in San Jose, California, was renamed Korematsu Court.

- There is a bronze statue of Korematsu in front of the San Jose Federal Building.

- Awards like the Alameda County Bar Association's Liberty Bell Award are named after him.

- On September 23, 2010, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signed a law. It made January 30 of each year Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution. This was the first time a day was named after an Asian American in the U.S.

- Since 2010, several other states, including Hawaii, Utah, and Illinois, have also started observing Fred Korematsu Day.

- Fred Korematsu was the first Asian American featured in "The Struggle for Justice." This is a permanent exhibit at the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery.

- On January 30, 2017, Google honored Fred with a special picture on its homepage called a Google Doodle.

- On December 19, 2017, the New York City Council also made January 30 Fred T. Korematsu Day.

- On October 27, 2021, Fred Korematsu received the Freedom Medal after his death.

See also

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |