Jean Rostand facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

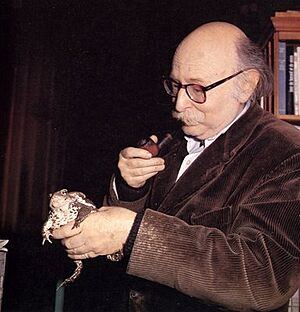

Jean Rostand

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 30 October 1894 Paris, France

|

| Died | 4 September 1977 (aged 82) Ville-d'Avray, Hauts-de-Seine, France

|

| Known for | Member of the Académie française |

| Parent(s) | Edmond Rostand Rosemonde Gérard |

| Relatives | Maurice Rostand (brother) |

| Awards | Kalinga Prize (1959) |

Jean Edmond Cyrus Rostand (born October 30, 1894 – died September 4, 1977) was a famous French biologist, writer, and thinker. He was known for his amazing work in science and for sharing his ideas with the public. Jean Rostand studied many areas of biology, like how animals develop from eggs. He also wrote many books about science, its history, and important ideas about life. He believed in human equality and freedom and spoke out against things like war and racism.

Rostand Island in Antarctica is named after him, showing his importance in the scientific world.

Contents

Jean Rostand's Life Story

Jean Rostand was born in Paris, France. His father, Edmond Rostand, was a famous writer of plays. His mother, Rosemonde Gérard, was a poet. He also had a brother named Maurice Rostand who was a writer too.

When he was six years old, his family moved to a place called Cambo-les-Bains. Growing up there, he became very interested in nature. He learned a lot from home tutors and read books by important scientists like Jean-Henri Fabre and Charles Darwin. Later, he studied natural sciences at the Sorbonne University and finished his studies in 1914.

Amazing Discoveries in Biology

Jean Rostand started his science work by studying insects like flies and silkworms. But he became very interested in how frogs develop.

In 1910, he did an amazing experiment. He made frog eggs develop without a male parent. This process is called parthenogenesis, which means "virgin birth."

He also looked at how some chemicals could cause frogs to have extra fingers or toes. This condition is called polydactyly. His work helped us understand how living things grow and develop, and what can cause changes in their bodies. He also studied how the sex of frogs is decided. For his important work in biology, he received several awards.

A Voice for Science and Humanity

Jean Rostand was not just a scientist; he was also a strong voice for important causes. He spoke out against nuclear weapons and the death penalty. He believed in human values and fairness for everyone.

He wrote several books about eugenics, which is the idea of improving the human race. He explored how humans are responsible for their own future and their place in nature.

Rostand was also very interested in the history of science. He showed how scientific facts are discovered slowly over time, often with many people working together. He believed scientists should be humble because mistakes can happen. For making science easy to understand for everyone, he won the Kalinga Prize in 1959.

In 1959, following in his father's footsteps, Jean Rostand was chosen to be a member of the Académie française. This is a very respected group in France that protects the French language and culture.

Jean Rostand is famous for a powerful quote from his 1938 book, Thoughts of a Biologist: "Kill one man, and you are a murderer. Kill millions of men, and you are a conqueror. Kill them all, and you are a God." This quote makes us think about power and how we view actions on a large scale.

He also thought about the future of biology. In 1959, he wrote about ideas like artificial birth and changing DNA, long before these ideas became common.

Jean Rostand's Personal Life

In 1920, Jean Rostand married his cousin, Andrée Mante. They had a son named François, who grew up to be a mathematician.

After 1922, Jean Rostand set up his own laboratory at his home in Ville d’Avray. This allowed him to do his research freely, without rules from big institutions. He often invited people from many different fields to his home on Sundays to discuss ideas. He passed away at home after a long illness.

Books by Jean Rostand

Jean Rostand wrote many books on science, philosophy, and society. Here are a few examples of his works:

- De la mouche à l’Homme, 1930 (From fly to man)

- L’Évolution des espèces, 1932 (The evolution of species)

- Pensée d’un biologiste, 1938 (Thoughts from a biologist)

- L’Homme, maître de la vie, 1941 (Man, master of life)

- Charles Darwin, 1947

- La biologie et l’avenir humain, 1949 (Biology and the human future)

- Ce que nous apprennent les crapauds et les grenouilles, 1953 (What toads and frogs teach us)

- Peut-on modifier l’Homme?, 1956 (Can we modify Man?)

- Science fausse et fausses sciences, 1958 (Erroneous science and false science)