Johann Heinrich Zedler facts for kids

Johann Heinrich Zedler (born January 7, 1706, in Breslau – died March 21, 1751, in Leipzig) was a German bookseller and publisher. His biggest achievement was creating a massive German encyclopedia called the Grosses Universal-Lexicon. This was the largest and most complete German encyclopedia of its time, the 18th century.

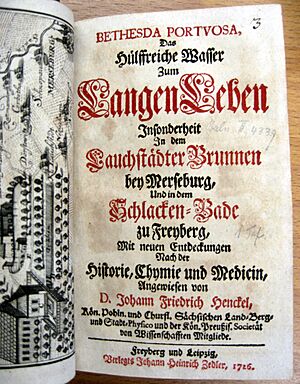

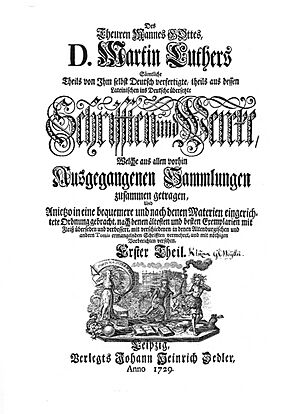

After training as a bookseller, Zedler started his own publishing company in 1726. It began in Freiberg and then moved to Leipzig in 1727. Leipzig was a big center for publishing and book trade. His first major project was an eleven-volume collection of Martin Luther's writings, published between 1729 and 1734.

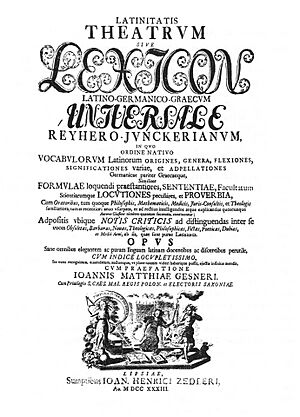

Zedler started the Universal-Lexicon in 1731. It grew to 64 volumes during his lifetime. This huge project led to long legal fights with other publishers in Leipzig. Their smaller, more specialized books felt threatened by Zedler's big encyclopedia.

Around 1737, Zedler faced financial problems. A Leipzig businessman named Johann Heinrich Wolf bought his company. Wolf provided money for Zedler to keep working on the Universal-Lexicon and other books. Zedler also published new works, like a business dictionary and a world atlas.

Zedler passed away in 1751 at age 45, just one year after the main part of the Universal-Lexicon was finished. People still remember him today, as the encyclopedia is often called "the Zedler."

Contents

Early Life and Beginnings

Johann Heinrich Zedler was born in 1706 in Breslau. His father was a shoemaker. It is believed that Zedler did not go to a higher school.

He started his career as an apprentice with booksellers in Breslau. Later, he worked for a bookseller and publisher in Hamburg. In 1726, he moved to Freiberg in Saxony. That September, he married Christiana Dorothea Richter, who was eleven years older than him. She was the sister of a publisher and the daughter of a respected merchant. Zedler used his wife's dowry (money or property given by the bride's family) to open his own bookshop in Freiberg. He did not stay long in Freiberg because the town was too small for a big book market.

Becoming a Publisher in Leipzig

First Big Publishing Project

In 1727, Zedler and his wife moved to Leipzig. This city was famous for its university and trade fairs. Soon after, Zedler's name appeared on a list of publishers in Leipzig. He announced his first published books in September, just before the Leipzig Michaelmas Fair. This was a good time to reach many visitors.

In 1728, Zedler announced a new edition of Martin Luther's writings. Unlike previous versions, Zedler's book organized Luther's works by topic, not by date. This project was planned for seven volumes.

Zedler used a common method called "Praenumeration" to fund the work. This meant interested people would pay for parts of the book in advance. They would get a discount and receive the books later. Zedler offered a very good price, making it hard for other booksellers to copy his idea.

To get enough money, Zedler also borrowed 2,665 thalers from his brother-in-law, David Richter. There was some uncertainty, but Zedler met his deadline. Within a year, his Luther series became a success, helping him build a strong publishing business.

Zedler often dedicated each volume of his books to important people. This was a common practice. The person named in the dedication, often with a portrait, would usually give a financial gift or an honorary title. Christian, Duke of Saxe-Weissenfels, gave Zedler his first honorary title. Zedler had dedicated the first and third volumes of Luther's writings to him.

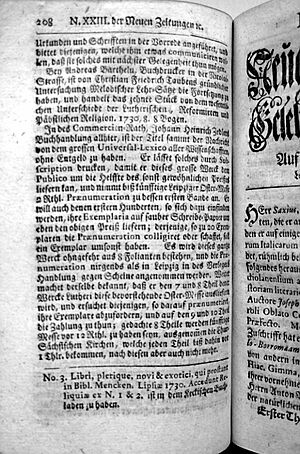

Announcing the Universal Lexicon

On March 26, 1730, Zedler announced his next big project. It was the Great Complete Universal Lexicon of Science and Art. He planned to make the first volume available through advance subscriptions.

Zedler wanted to combine many existing reference books into one huge work. This was a big challenge to the established publishers in Leipzig. Other publishers had already made their own encyclopedias or dictionaries. For example, Johann Friedrich Gleditsch had published a household lexicon. Thomas Fritsch had published a historical lexicon. Johann Theodor Jablonski had published a lexicon of arts and science. Zedler's new project threatened all these existing works.

Five weeks after Zedler's announcement, Caspar Fritsch, whose father had published a historical lexicon, reacted. He was worried about his sales. He announced special prices for his own book and emphasized that his work was already well-known and reliable.

Fighting for Copyright Protection

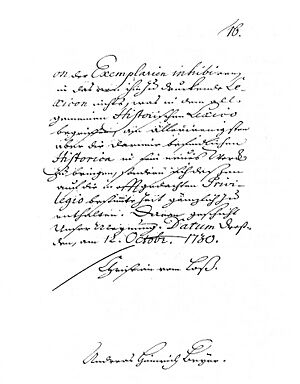

On September 13, 1730, Zedler asked for a special printing right (a "privilege") from Saxony. This privilege would protect his lexicon from being copied by others for five to ten years. The Leipzig Book Commission, which handled these requests, posted Zedler's plan in all bookstores. This allowed others to object.

Both Caspar Fritsch and Johann Gottlieb Gleditsch objected. Fritsch argued that his father already had a privilege for his historical lexicon. He claimed Zedler's lexicon would be too similar. On October 16, 1730, a court in Dresden agreed with Fritsch and Gleditsch. They rejected Zedler's request. They also warned him that he would be fined if he copied anything from the General Historical Lexicon. Zedler lost this first round against his rivals.

The "Publishers War" Continues

Even after the court's decision, Zedler kept working on his project. On October 19, 1730, he announced that he was still taking advance subscriptions. He denied all accusations of copying. He said his Universal-Lexicon was being written by smart and learned people who did not need to plagiarize.

Zedler also said he would not be stopped by "envious enemies." He planned to release other important works, like a General Chronicle of States, Wars, Religion and Scholarship. He had support from Jacob August Franckenstein, a professor at the University of Leipzig.

Other publishers protested again. The Leipzig Book Commission ordered Zedler to stop printing and advertising his works. They also told him to publish their decision or pay a fine.

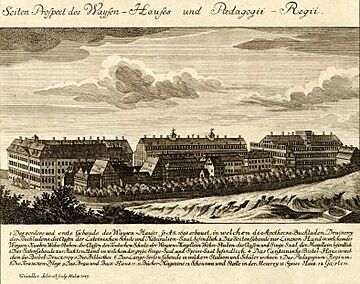

With his Universal Lexicon in trouble, Zedler moved its production to nearby Prussia. In Halle, he connected with Johann Peter von Ludewig, a lawyer and university chancellor. Ludewig arranged for an orphanage in Halle to print the Universal-Lexicon. Before starting, Zedler asked for special printing rights from the Prussian King and the Holy Roman Emperor. He received the Emperor's privilege on April 6, 1731, and the Prussian King's privilege four days later.

First Volume and Challenges

Zedler could not deliver the first volume of the Lexicon by Easter 1731 as planned. He announced it would be ready for the Michaelmas Fair in October. He also proudly stated that he was protected by the Prussian King, Frederick William I.

Jacob August Franckenstein edited the first volume, and Johann Peter von Ludewig wrote the introduction. The names of other writers were kept secret. This was a strategy to protect them from lawsuits about stealing ideas. Von Ludewig said the Lexicon was the work of Zedler's "nine muses" and their names would be revealed later. This promise was never kept. The first volume marked the start of "Europe's largest Encyclopedia project of the 18th Century."

More Problems and Changes

Leipzig publishers quickly reacted. During the Michaelmas Fair in 1731, the Leipzig Book Commission ordered all printed copies to be seized. Zedler protested, but the order stood. He appealed to a higher court in Dresden and got a partial win. On December 14, 1731, the court allowed him to give books to his advance subscribers, as long as the books were printed outside Saxony. This allowed Zedler to continue, but added transport costs.

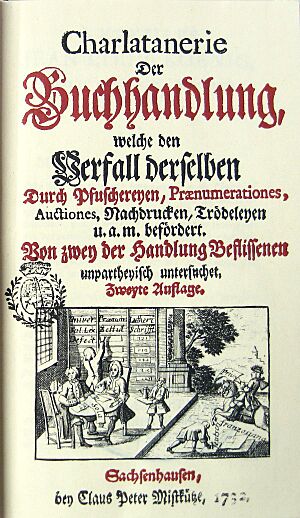

Around this time, a pamphlet (a small book) appeared, criticizing the "charlatanism" (fake practices) of booksellers. It accused Zedler of fraud and said his authors were stupid. Zedler's response is not known.

Zedler's opponents did not give up. They demanded he pay the 300 thaler fine from October 1730. On March 10, 1732, the court asked for a new report from Leipzig. This report listed 87 pages of plagiarism claims against Zedler. On April 24, the court ruled that Zedler must pay the fine and banned him from printing in Saxony.

On October 26, 1732, Zedler faced another setback. Jacob August Franckenstein, his editor, publicly announced he would no longer work with Zedler. Franckenstein died a few months later. After his death, Paul Daniel Longolius became the editor of the Universal Lexicon.

Financial Struggles

In early 1733, Zedler tried new things to improve his business. He launched a monthly magazine about world news, which was successful for a while. In March 1733, he bought another publishing house, Johann Herbord Kloss's. Kloss had many titles, but many were not popular.

By June, Zedler was already trying to sell off 10,000 books from this new collection, many of which were "junk." This showed he was having financial problems and needed quick cash. In October, another bookseller offered Zedler's books at big discounts.

The main problem was finishing the last volume of Luther's writings. This project had been a steady source of income. Now, the costs for the final volume had to be paid without new advance payments.

In December 1733, Zedler's magazine gained sales by adding war news. But soon, he faced competition from another Leipzig publisher, Moritz Georg Weidmann. Zedler continued to offer low prices to sell his books.

Trying a Book Lottery

In 1735, Zedler tried a new way to get cash: a book lottery. He promised that everyone would win books equal to what they paid. They would also get a ticket for a draw of valuable books. The draw was planned for April 18, 1735. Zedler also promised to donate some earnings to a Leipzig orphanage.

Zedler's rivals, led by Weidmann, opposed the lottery. They argued that the Universal Lexicon was among the prizes, and its sale in Saxony was still banned. Zedler did not get an immediate answer from Dresden, so he missed the draw date. On May 28, the lottery was approved, but only if the Universal-Lexicon was removed from the prizes. This was likely the most attractive prize.

Zedler continued to face difficulties. Another competitor went out of business, flooding the market with cheap books. In October 1735, Zedler advertised his lottery again. Soon after, he announced another auction of thousands of books and engravings. By April 1736, Zedler was offering his lottery tickets at very low prices. This suggests he was in serious financial trouble and needed to sell his books at any cost.

Financial Collapse

The exact details of Zedler's financial collapse are not fully clear. It is known that he could no longer pay his creditors. Some historians believe he went bankrupt around 1735 or 1736. Modern biographies do not go into the exact date or details of his financial collapse.

New Beginnings: Wolf and Heinsius

A Fresh Start and Fighting Copies

The Leipzig businessman Johann Heinrich Wolf helped Zedler make a new start. Wolf was described as someone who loved science and good books. He believed in the Universal Lexicon and wanted it to continue. The exact details of their agreement are not known.

On August 5, 1737, Zedler's imperial privilege for printing the Universal Lexicon was stopped. Zedler claimed it was because he failed to deliver copies to the imperial court. However, it is thought that another publisher, Johann Ernst Schultze, influenced this decision. Schultze knew about Zedler's financial problems. He also found Paul Daniel Longolius, Zedler's former editor, to work for him. After Zedler lost his privilege, Schultze got an imperial privilege for himself in June 1738.

Schultze printed volumes 17 and 18 of the Universal-Lexicon and tried to sell them in Leipzig. But the Leipzig Council stopped him, saying his imperial authority did not apply in their city. This was good news for Zedler, as it protected his lexicon.

Carl Günther Ludovici, a professor, took over as editor of the Universal Lexicon from Volume 19. Ludovici improved the encyclopedia by adding more complete bibliographies and longer articles. Schultze stopped printing the lexicon in 1745 due to his own financial problems.

Taking a Step Back

After Wolf took over his publishing house, and Ludovici became the main editor, Zedler became less involved. He seems to have given up his own bookstore. An advertisement from 1739 stated that the latest encyclopedia volumes were available from "Wolf's vault."

Zedler began to return to a more private life. An article about Zedler in the Universal Lexicon itself (published in 1749) mentioned that he chose other work after Wolf took over. Zedler owned property in Wolfshain, a village near Leipzig. Some believe he retired there to plan new publishing projects. However, he needed to publish under a new name to avoid past problems.

New Projects with Heinsius

In 1740, some of Zedler's books started appearing under the name of Johann Samuel Heinsius, another Leipzig bookseller. This included a new version of Zedler's magazine.

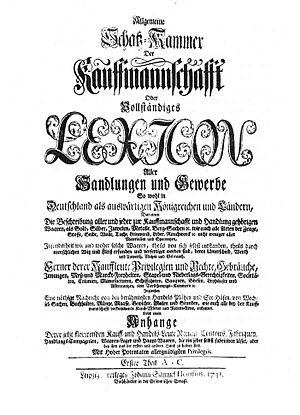

In 1741, the first volume of the General Treasure Chamber was published. This was a four-volume business dictionary translated by Ludovici. The last volume was delivered in 1742, and a supplement came out a year later.

Zedler's next project was the Corpus Juris Cambialis (Stock Exchange Laws) by Johann Gottlieb Siegel. Heinsius advertised this two-volume book in 1742, asking for advance subscribers. Both volumes were ready for the Leipzig Michaelmas Fair that year.

After these projects, Zedler started another major publishing work. This was Heinsius's Historical and Political-Geographic Atlas of the whole world. It was a German translation of a French geographical dictionary. The German version had 13 volumes, published by Heinsius between 1744 and 1749.

Final Years and Passing

Zedler likely started other projects too. The Universal Lexicon article about him in 1749 said he had "several large works that are already being printed." However, Zedler's direct influence on later projects became less clear.

In the years leading up to 1751, Wolf's company continued to publish under Heinsius's name. They released two volumes of the Universal Lexicon and one volume of the General state, war, religious and scholarly chronicle each year. The main alphabetical volumes of the Universal Lexicon were completed by 1750. Later, Ludovici added four more supplementary volumes.

Zedler spent most of his last years on his estate near Leipzig. The Universal Lexicon article said he still gave useful advice to the firm. Zedler's supporter, Johann Peter von Ludewig, had died in 1743. Heinsius died in December 1750. On March 21, 1751, Zedler also passed away. His wife, Christiana Dorothea, moved back to Freiberg in 1754 and died in 1755. They did not have any children.

See also

In Spanish: Johann Heinrich Zedler para niños

In Spanish: Johann Heinrich Zedler para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |