Katherine Chidley facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Katherine Chidley

|

|

|---|---|

| Personal details | |

| Born | Unknown: probably 1590s. Probably Shrewsbury. |

| Died | 1653 or later. London |

| Political party | Levellers |

| Spouse | Daniel Chidley |

| Relations |

|

| Profession | Haberdasher |

| Signature | |

Katherine Chidley (active 1616–1653) was an English activist who believed in a simpler form of Christianity called Puritanism. She first became known for resisting the official church rules and helping to form separate religious groups in Shrewsbury and London.

During the English Civil War, Katherine became a strong supporter of the Independents, a group who believed churches should be self-governing. Later, under the new government, she became a leader among Levellers women. The Levellers were a political movement that wanted more rights for ordinary people. Katherine was especially famous for her work in helping John Lilburne, a key Leveller leader.

Contents

Life in Shrewsbury

We don't know much about Katherine Chidley's early life or even her family name. She first appears in records in Shrewsbury as the wife of Daniel Chidley. Daniel was a tailor, and his name was sometimes spelled Chidloe.

Katherine and Daniel had eight children christened at St Chad's Church, Shrewsbury between 1618 and 1629. Their first son, Samuel, was born in 1618. They named two other sons Daniel, after their father, because the first Daniel died as a baby.

Challenging Church Rules

Katherine Chidley often challenged the rules of the Church of England. For example, after her children were born, she refused to take part in a special church service for mothers. Many Puritans disliked this ceremony.

In 1626, Katherine and other women were called before the church authorities for refusing this service. Katherine and Daniel were also among twenty people who were reported for not attending church. This suggests they might have been part of a secret religious group.

The local preacher, Julines Herring, believed the Chidleys were "separatists." This meant they wanted to completely separate from the Church of England, unlike other Puritans who just wanted to reform it from within. Herring thought their ideas were dangerous.

Even though they had strong beliefs, the Chidleys continued to have their children christened at St Chad's. This was unusual for separatists. By 1629, they likely felt they needed to move to find people who shared their radical views. They also might have moved for better work opportunities. Their time in London made their beliefs even stronger.

Moving to London

By 1630, Katherine and Daniel Chidley were active in London. Daniel helped to start a new separatist church. This group broke away from another church because they refused to have any contact with the Anglican churches.

The Chidleys were involved in this secret movement against the official church throughout the 1630s. They even took part in destroying a church item called a surplice at Greenwich, which they saw as a very unholy place.

After moving to London, the Chidleys also did better financially. Daniel became a member of the Worshipful Company of Haberdashers in 1632. This was a powerful trade group for people who sold small items like needles and thread. Their eldest son, Samuel, also started an apprenticeship in 1634.

Spreading Their Beliefs

In 1647, Katherine and her son Samuel traveled to Suffolk to do missionary work. They helped to set up new churches there. A writer named Thomas Edwards described Katherine as an "old Brownist" (another name for a separatist) and Samuel as a "young Brownist." He said they were spreading their ideas outside London.

They helped found a church in Bury St Edmunds. This church's agreement was very radical. It stated that they were completely separated from the Church of England and all other churches that didn't follow Christ's teachings exactly. They promised not to return to what they called "vain inventions" or "idolatries."

Eight adults and six children joined this new church. Katherine and Samuel Chidley signed as witnesses. The first pastor of this church was John Lanseter.

Edwards criticized the Chidleys' work, even mocking a pamphlet they wrote. He claimed Katherine and Samuel worked together, with "one inditing, the other writing." Despite the criticism, it seems the Chidleys continued to travel and establish new separatist churches during this time of change.

Business and Family

Daniel Chidley became a leader in the Haberdashers' Company in 1649 but died shortly after. Their son, Samuel, also became a full member of the company that same year.

Katherine Chidley took over her husband's business. She became a government contractor, supplying goods to the army. For example, in 1651, she was paid large sums of money for providing thousands of pairs of stockings to the army in Ireland.

Katherine's Children

Katherine and Daniel Chidley had eight children christened at St Chad's Church in Shrewsbury:

- Samuel, born April 13, 1618. He also became a Leveller activist.

- Daniel, born August 20, 1620. He died as a baby in 1621.

- Priscilla, born April 22, 1622.

- Sarah, born April 11, 1624.

- Daniel, born February 12, 1626.

- Mary, born February 25, 1627.

- Joseph, born September 14, 1628.

- John, born October 26, 1629.

Leveller Leader

Katherine Chidley became a key leader among Leveller women. The Levellers were a group who wanted more fairness and rights for everyone in England. They often presented petitions to Parliament.

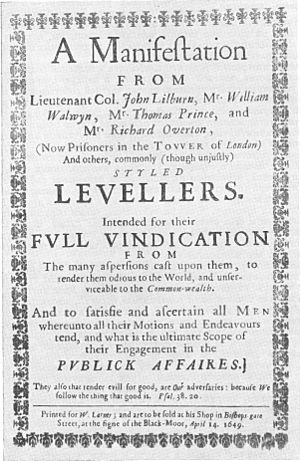

In April 1649, four Leveller leaders, including John Lilburne, were sent to prison. They were accused of writing a book that criticized the government. Many women, led by Katherine, protested their arrest.

Women Petition Parliament

On April 23, 1649, hundreds of women went to Parliament with a petition asking for the release of the Leveller leaders. They were turned away, but they returned the next day.

On April 25, they tried a third time. Parliament sent a message telling them: "The matter they petitioned about was of an higher concernment than they understood; that the house gave an answer to their husbands, and therefore desired them to go home, and look after their own business, and meddle with their housewifery." This meant Parliament thought women shouldn't be involved in politics.

This insulting answer made the women even more determined. On May 5, 1649, they presented their "Humble Petition of divers well-affected women." Katherine Chidley might have written this petition. In it, the women argued that they had "an interest in Christ equal unto men" and deserved the same freedoms as men. They pointed out that if men could be treated unfairly, so could women. This public pressure likely helped the four Leveller leaders eventually gain their freedom.

When John Lilburne was on trial again in 1653, Katherine Chidley once more supported him. She organized a petition to Barebone's Parliament, which was signed by over 6,000 women. Katherine led a group of twelve women to present this petition. Even when a Member of Parliament tried to stop them, they refused to give up. Another member then told them Parliament could not accept their petition because "they being women and many of them wives, so that the Law tooke no notice of them."

Death

We don't know what happened to Katherine Chidley after 1653, and her exact death date is unknown.

Images for kids