Kra–Dai languages facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Kra–Dai |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tai–Kadai, Daic | |||

| Ethnicity: | Daic people | ||

| Geographic distribution: |

Southern China, Hainan Island, Indochina, and Northeast India |

||

| Linguistic classification: | One of the world's primary language families | ||

| Proto-language: | Proto-Kra–Dai | ||

| Subdivisions: |

Kra

Kam–Sui

Lakkia

Biao

Be

Hlai

|

||

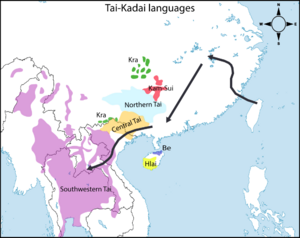

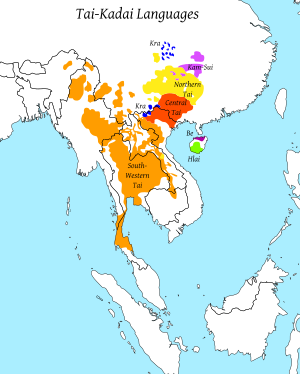

Distribution of the Tai–Kadai language family.

|

|||

The Kra–Dai languages are a group of languages spoken in Mainland Southeast Asia, Southern China, and Northeastern India. You might also hear them called Tai–Kadai or Daic languages.

These languages are special because they are tonal. This means the meaning of a word can change based on the pitch of your voice. Think of it like singing a word differently to make it mean something else! Two well-known Kra–Dai languages are Thai and Lao. These are the official languages of Thailand and Laos.

About 93 million people speak Kra–Dai languages. A large number of these speakers, around 60%, speak Thai. There are about 95 languages in this family, with 62 of them belonging to the Tai branch.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name "Kra–Dai" was suggested by a linguist named Weera Ostapirat in 2000. It combines the names of two main branches: Kra and Dai. These names come from how the speakers of those languages refer to themselves. Most experts who study languages in Southeast Asia now use "Kra–Dai."

You might also see the name "Tai–Kadai" used in some places. However, many experts think this name can be confusing. It came from an older idea that the language family had only two main parts: Tai and Kadai. This idea is now considered outdated. The term "Kadai" itself has been used in different ways, sometimes for the whole family, and sometimes just for the Kra branch. This is why "Kra–Dai" is preferred to avoid confusion.

Where Did They Come From?

Experts believe the Kra–Dai language family started a very long time ago, possibly around 1200 BCE. This was in the middle of the Yangtze basin in China. The fact that there are many different Kra–Dai languages in Southern China suggests this area was their original home.

The Tai branch of this family, which includes Thai and Lao, started moving south into Southeast Asia much later, around 1000 AD.

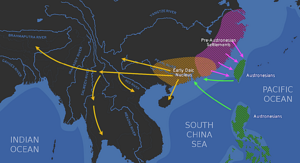

Some researchers also think that Kra–Dai languages might be related to Austronesian languages. These are languages spoken across many islands, including those in the Philippines and Indonesia. It's like they might share a very ancient common ancestor! One idea is that Kra–Dai languages might have developed from an Austronesian group that moved from Taiwan back to mainland China.

Evidence of Kra–Dai languages has even been found in old Chinese writings, like on bronze objects. This shows that these languages were spoken in areas of China long ago.

How Are They Grouped?

The Kra–Dai family has at least five main branches that linguists agree on:

- Tai: Spoken in Southern China and Southeast Asia.

- Kra: Found in Southern China and Northern Vietnam.

- Kam–Sui: Spoken in Guizhou and Guangxi in China.

- Be: Spoken on Hainan Island.

- Hlai: Also spoken on Hainan Island.

Some Kra–Dai languages are a bit harder to classify. For example, Lakkia and Biao have unique words. Jiamao from Southern Hainan is usually grouped with Hlai, but it has words from other sources too.

There are also Kra–Dai languages that are a mix of different language groups. For example:

- Hezhang Buyi mixes Northern Tai and Kra.

- E is a mix of Northern Tai and a Chinese dialect called Pinghua.

- Caolan combines Northern Tai and Central Tai.

- Sanqiao has elements from Kam–Sui, Hmongic, and Chinese.

Connections to Other Language Families

Linguists are always trying to figure out how language families are related. Here are some ideas about Kra–Dai:

Austro-Tai Connection

Many scholars believe that Kra–Dai languages might be related to, or even a part of, the Austronesian languages. They have found similar words and sound patterns that suggest a shared history. Some think they are like "sister" families, while others believe Kra–Dai might have branched off from Austronesian and moved back to the mainland.

Sino-Tibetan Idea

In the past, some thought Kra–Dai languages were part of the Sino-Tibetan languages family, which includes Chinese and Tibetan. This was because they share many similar words. However, most experts outside China now believe these similar words are actually borrowed from Chinese. They see Kra–Dai as its own separate language family. In China, however, some still group them together.

Hmong-Mien Connection

There's also a theory that Kra–Dai languages might be related to the Hmong–Mien languages. This idea is based on some shared words. It's possible these similarities come from languages being in contact in coastal China, or from an even older shared ancestor.

Japonic Connection

One interesting idea suggests that Japonic languages (like Japanese) might have originated in Southern China. While not directly related by ancestry, some experts think that Proto-Japanese might have shared features with Kra–Dai languages because they were spoken near each other and influenced each other a lot.

Images for kids

-

Map of the Chinese plain at the start of the Warring States Period in the 5th century BC.

See also

In Spanish: Lenguas kra-dai para niños

In Spanish: Lenguas kra-dai para niños