Lac-Mégantic rail disaster facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Lac-Mégantic rail disaster |

|

|---|---|

Police helicopter view of Lac-Mégantic, the day of the derailment

|

|

| Details | |

| Date | July 6, 2013 01:14EDT (05:14 UTC) |

| Location | Lac-Mégantic, Quebec |

| Coordinates | 45°34′40″N 70°53′6″W / 45.57778°N 70.88500°W |

| Country | Canada |

| Operator | Montreal, Maine and Atlantic Railway |

| Incident type | Derailment of a runaway train, explosion |

| Cause | Neglect, defective locomotive, poor maintenance, driver error, flawed operating procedures, weak regulatory oversight, lack of safety redundancy |

| Statistics | |

| Trains | 1 |

| Deaths | 47 (42 confirmed, 5 presumed) |

| Damage | More than 30 buildings destroyed, 36 to be demolished due to contamination |

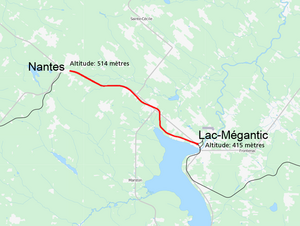

The Lac-Mégantic rail disaster happened in the town of Lac-Mégantic, Quebec, Canada. It occurred on July 6, 2013, around 1:14 a.m. EDT. An unattended 73-car Montreal, Maine and Atlantic Railway (MMA) freight train was carrying crude oil. It rolled downhill from Nantes and derailed in downtown Lac-Mégantic. This caused many tank cars to explode and catch fire.

Forty-seven people died in the accident. More than 30 buildings in the town center were destroyed. This was about half of the downtown area. Almost all of the remaining buildings had to be torn down because of oil pollution. This disaster was the fourth-deadliest rail accident in Canadian history. It was also the deadliest involving a non-passenger train.

Contents

Understanding the Disaster

The Railway Line

The railway line that goes through Lac-Mégantic was owned by a U.S. company called Montreal, Maine and Atlantic Railway (MMA). MMA had owned this line since 2003. It connected parts of Quebec and Maine.

This railway line was built in the late 1880s. It was part of a larger system connecting Montreal and Saint John. There was a plan in the 1970s to move the line away from downtown Lac-Mégantic. However, it was never done because it was too expensive.

Over the years, the railway line changed owners several times. In 2003, Rail World Inc. bought the line and created MMA. MMA tried to save money by cutting costs for freight train operations. They also didn't do enough maintenance on the tracks. This made many parts of the track unsafe. By 2013, trains had to slow down in many areas because the tracks were in poor condition.

The Train and Its Cargo

The freight train, called "MMA 2", was very long and heavy. It had five locomotives and 72 tank cars. These tank cars were carrying crude oil from the Bakken Formation. The oil was on its way to a refinery in New Brunswick.

Most of the tank cars were a type called DOT-111. In 2009, these cars made up a large part of the train fleet in the U.S. and Canada. However, they were known to break open easily in accidents. Even before the Lac-Mégantic accident, there were efforts to make these cars safer or replace them. But these changes were delayed because railway and oil companies worried about the cost.

Single Person Train Operation

MMA trains were allowed to operate with only one person, called Single Person Train Operation (SPTO). This was a way for the company to save money. However, many people criticized this decision. They worried about safety. For example, if the engineer had a medical problem, no one else would be there to take over.

Some former railway workers had concerns about SPTO. They said that having two people could help catch mistakes. They felt that MMA was cutting too many costs, which could affect safety. The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) looked into whether SPTO played a role in the accident. They couldn't say for sure if another crew member would have prevented it.

Train Brakes

Trains use two main types of brakes: air brakes and hand brakes. Air brakes work by using air pressure. If a locomotive is turned off, the air compressor stops supplying air to the brakes. Over time, air can leak out, making the air brakes less effective.

Hand brakes are mechanical devices. They apply brake shoes directly to the wheels. Their effectiveness depends on how well they are maintained and how much force is used to apply them. Experts estimated that between 17 and 26 hand brakes would have been needed to secure the train. If there had been a two-person crew, they could have tested the hand brakes properly. This test would ensure the hand brakes alone could hold the train.

What Happened

Before the Derailment

In October 2012, the lead locomotive, #5017, had engine problems. It was repaired with a material that wasn't strong enough. This led to issues like engine surges and smoke. On the night of the disaster, oil built up in the turbocharger, overheated, and caught fire.

On July 5, the train stopped in Nantes, about 11 km west of Lac-Mégantic. The engineer, Tom Harding, parked the train on the main line. He shut down four of the five locomotives. He left the lead locomotive running to keep air pressure to the air brakes. He also set some hand brakes. The train could not be parked on a safer side track because it was being used to store other rail cars.

Harding tried to test the brakes, but he made a mistake. He left the locomotive air brakes on, which made it seem like the hand brakes were holding the train by themselves. This was not true. He then left the train unattended.

Later that night, people noticed thick smoke and sparks coming from the lead locomotive. The Nantes Fire Department responded to a 911 call. They put out the fire by shutting down the engine. This stopped the fuel from circulating. After the fire was out, MMA employees arrived and told the police and rail traffic controller that the train was safe. The firefighters then left.

However, shutting down the locomotive also stopped the air compressor. This meant the air brakes would slowly lose pressure. The TSB found that MMA's rules for parking trains were not strong enough. They also found that Transport Canada had warned MMA many times about not setting enough hand brakes on parked trains, but no fines were given.

The Train Rolls Away

With the locomotives shut down, the air brakes slowly lost pressure. At 12:56 a.m., the air pressure dropped too low. The combination of air brakes and hand brakes could no longer hold the train. It began to roll downhill towards Lac-Mégantic, which was about 11 km away. The train was moving without its lights on.

The tracks were not equipped with special sensors to warn controllers about a runaway train. As it gained speed on the downhill slope, the train entered Lac-Mégantic at a very high speed. The TSB later said the train was going about 105 km/h. This was much faster than the 16 km/h speed limit for that area.

Just before the derailment, witnesses saw the train speeding through crossings. There were no locomotive lights, and sparks were flying from the wheels. The crossing signals did not even activate because the train was moving so fast.

Derailment and Explosions

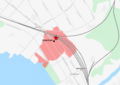

The unmanned train derailed in downtown Lac-Mégantic at 1:14 a.m. It happened near the main street, Frontenac Street. People at a nearby bar, Musi-Café, saw the tank cars leave the tracks. They fled as a huge fireball erupted.

Several explosions happened as the tank cars broke open and crude oil spilled out. The heat from the fires was felt up to 2 km away. People jumped from buildings to escape the flames. The burning oil flowed into the town's storm sewers. It then came out as huge fires from manholes, chimneys, and basements.

The five locomotives and a special remote-control car stayed on the tracks. They separated from the rest of the train and came to a stop about 1 km away. Most of the 72 tank cars derailed. Nine tank cars at the back of the train did not explode. Emergency workers moved them away from the fire. About six million liters of crude oil spilled, and the fire started almost immediately.

Impact and Damage

The disaster caused massive damage to Lac-Mégantic. At least 30 buildings in the town center were destroyed. This included the library, post office, and many businesses and homes. In total, 115 businesses were destroyed or became unusable. The Musi-Café was completely destroyed.

The mayor of Lac-Mégantic, Colette Roy-Laroche, said that the town would rebuild. But she also noted that many historic buildings were lost forever. Many businesses had to move to temporary locations. The town's water supply was shut down due to leaks and contamination.

The industrial park also lost rail service for several months. The total cost of damages and cleanup was very high.

Aftermath and Changes

Cleanup Efforts

The downtown area was heavily contaminated with chemicals like benzene. Firefighters and investigators had to work in short shifts because of the heat and toxic conditions. The waterfront and marina were also polluted.

Many homes were no longer safe to live in because the soil was contaminated. Some areas might take up to five years to clean up. This forced many families to rebuild elsewhere. The town considered making a memorial park in the damaged area. They also planned to move displaced businesses to a new commercial district.

Railway Company Response

The president of Rail World, Edward Burkhardt, visited the town a few days after the accident. Residents were very angry with him. The railway's safety record was questioned. Data showed that MMA had a much higher accident rate than other U.S. railways.

MMA later filed for bankruptcy protection in both Canada and the United States. The Canadian Transportation Agency suspended MMA's operating license because the company did not have enough insurance. This stopped all train operations on the line.

Other major Canadian railway companies, like Canadian Pacific Railway and Canadian National Railway, changed their rules. They said they would no longer leave unattended trains with dangerous goods on main lines.

Safety Improvements

As a result of the disaster, many changes were made to railway safety rules. In December 2013, MMA was allowed to operate trains through Lac-Mégantic again. However, there were strict new rules. Trains carrying dangerous goods were not allowed to park near the town center. Also, trains had to have both a conductor and an engineer on board. Their speed was limited to 16 km/h.

In 2016, it was announced that all DOT-111 tank cars would be removed from transporting crude oil in Canada. A new, safer tank car design, the TC-117, became the new standard. There are also plans to reroute the tracks around Lac-Mégantic to keep trains away from the town center.

Environmental Impact

The disaster caused serious environmental damage. The Chaudière River was contaminated by an estimated 100,000 liters of oil. The oil spill traveled down the river, affecting towns downstream. Residents were asked to limit their water use, and swimming and fishing were banned in the river.

Environmental experts reported high levels of harmful chemicals in the water and soil. The cleanup efforts were very difficult and expensive. The provincial government ordered MMA and other companies involved to pay for the full cost of the cleanup.

Rebuilding the Community

The community of Lac-Mégantic worked hard to rebuild. New commercial buildings were constructed to help businesses that were displaced. A new bridge was planned to connect parts of the town.

Students from several universities collected tens of thousands of books to create a new library. The new library, named La Médiathèque municipale Nelly-Arcan, opened in May 2014.

The Musi-Café, a popular bar destroyed in the fire, also reopened in a new building in December 2014. Many Quebec musicians held benefit concerts to raise money for the town's rebuilding efforts. Other businesses, like grocery stores and pharmacies, also reopened in new locations.

The people of Lac-Mégantic continue to push for the railway tracks to be moved outside the town. This would help prevent another disaster.

Images for kids

-

The Lieutenant Governor-in-Council ordered all provincial flags to be flown at half mast on public buildings for 7 days following the derailment.

See also

In Spanish: Accidente ferroviario de Lac-Mégantic de 2013 para niños

In Spanish: Accidente ferroviario de Lac-Mégantic de 2013 para niños