Landing on Long Island facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Landing on Long Island |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War II, Pacific War | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 220 | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| none | |||||||

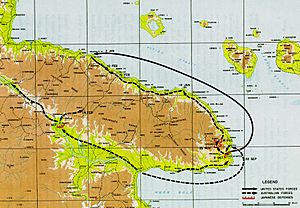

The Landing on Long Island was an important event during World War II. It happened in the Territory of New Guinea on 26 December 1943. This landing was part of the Huon Peninsula campaign. This campaign was a bigger plan called Operation Cartwheel, led by General Douglas MacArthur. His goal was to surround and cut off the main Japanese base at Rabaul.

Long Island is located at the northern end of the Vitiaz Strait. It was a key stop for Japanese boats moving supplies between Rabaul and Wewak. A group of 220 Australian and American soldiers landed on the island. Luckily, there were no Japanese soldiers there at the time, so there was no fighting. This landing marked the furthest point the Allied forces had reached into Japanese-held territory. After the landing, the island was turned into a radar station.

Contents

Island Details and War Strategy

Long Island's Geography

Long Island is a circular island at the northern end of the Vitiaz Strait. It is about 14 miles (23 km) across, covering an area of about 160 square miles (414 km²). The island has two tall peaks: Mount Reamur in the north (4,278 feet or 1,304 meters) and Cerisy Peak in the south (3,727 feet or 1,136 meters).

Most of the island's center is taken up by Lake Wisdom, which is 500 feet (152 meters) above sea level. Inside the lake, there is an active volcano. The island's population was about 250 native people. Long ago, a huge volcanic eruption in 1660 covered the island in 30 meters (98 feet) of ash. This was one of the biggest eruptions in the last 2,000 years.

Why Long Island Was Important

In late 1943, the war in the South West Pacific Area was focused on General Douglas MacArthur's plan, Operation Cartwheel. This plan aimed to cut off and weaken Rabaul, which was the main base for Japanese forces. The Huon Peninsula campaign started well for the Allies. They had victories at landing at Lae and landing at Nadzab. However, bad weather, difficult land, and strong Japanese resistance made progress slow.

The Allies wanted to stop the Japanese supply line. The Japanese used boats to move supplies along the coast between Madang and Fortification Point. Long Island was a key stop for these Japanese supply boats. If the Allies controlled Long Island, it would be a great place for a radar station and an observation post. This radar would help protect the upcoming landing at Saidor.

On 22 December 1943, Lieutenant General Walter Krueger, who commanded the Alamo Force, ordered the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade to take Long Island. This mission was called "Sanatogen." It happened at the same time as the landings around Cape Gloucester on New Britain.

Getting Ready for the Landing

A small team of coastwatchers landed on Long Island on 6 October 1943. These were three Australians from the Allied Intelligence Bureau (AIB) and four local people. Their job was to watch for Japanese aircraft coming from Madang. They reported that the Japanese had left the island in November.

Major Leonard Kaplan, the mission commander, flew to Finschhafen on 22 December. He then took a PT boat to Long Island on 23 December. He landed at 11:45 PM, guided by lights set up by the AIB team. After confirming no Japanese were present, Kaplan returned to Finschhafen. He left two scouts behind to explore the island and set up lights for the landing boats.

Meanwhile, on 22 December, soldiers from the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade left Oro Bay for Finschhafen. This was where the attack would start. A group of 3 officers and 32 men from the 592nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment (EBSR) operated three LCVPs and five LCMs. One LCVP was used for navigation. The other two LCVPs and one officer and eight men stayed on Long Island with the soldiers. The main landing force was 150 men from Company D, Shore Battalion, 592nd EBSR.

At Finschhafen, they met Australian soldiers from No. 338 Radar Station RAAF. These Australians would operate the radar on Long Island. They had flown in from Jacksons and Wards Airfields near Port Moresby. There were 35 RAAF personnel in total. This brought the total landing force to 220 men. A practice landing planned for 24 December was canceled due to an air raid warning.

General Krueger helped plan the final landing. A last meeting was held at 8:30 AM on 25 December. All boats were loaded by noon. The men then enjoyed a Christmas dinner of roast turkey. The equipment included two 37 mm guns, four 60 mm mortars, four bazookas, a 5,000-gallon (18,927-liter) water tank, a bulldozer, two jeeps, a jeep trailer with a water tank, and two .50-caliber machine guns.

The Landing on Long Island

The LCMs and LCVPs started their 105-mile (169 km) journey from Finschhafen at 2:15 PM. They traveled along the coast in daylight without being attacked by Japanese aircraft or ships. Three PT boats, carrying 90 men of Company D (the first group to land), left Finschhafen at 6:00 PM. Being faster, they passed the landing craft during the night.

They arrived off Malala at 11:45 PM, a little late. But this didn't matter because there was no bombing or naval attack needed, as no Japanese were present. The men moved from the PT boats to six rubber boats. This was tricky because they hadn't practiced. Guided by the lights set up by the scouts on shore, the rubber boats set off at 12:20 AM. The waves were rough, and two boats flipped over. However, no men or equipment were lost. The entire first group landed safely by 2:00 AM on 26 December.

The second group, the landing craft, arrived off the island at 5:20 AM, 80 minutes late. The beach was steep, with waves 4 to 6 feet (1.2 to 1.8 meters) high. The force waited until daylight. Then, two LCMs tried to land but failed. They got stuck, and the radar equipment got soaked in salt water. The soldiers then searched for a better beach and found one south of Cape Reamur. About 100 tons of equipment were unloaded by 1:00 PM. The navigation LCVP and five LCMs then sailed back to Finschhafen. The radar equipment was moved inland and covered. That night, heavy rains caused Lake Wisdom to overflow, and the equipment was hit by a rush of fresh water.

After the Landing

On 27 December 1943, the radar equipment was moved to a 150-foot (46-meter) hilltop on the east coast. Two 1,700-pound (771 kg) generators were pulled on sleds. The radar station crew found it very hard to keep the equipment working in the hot, wet, and humid climate. There were many breakdowns. The wet season began by the end of December, which affected the equipment. New power supplies and a replacement transmitter and receiver for the radar arrived on 27 January 1944.

By April 1944, the Allies had moved along the coast to Madang. The main Japanese air threat was now coming from Wewak. So, No. 338 Radar Station was ordered to move to Matafuna Point on the west coast. This move took a week. A flying fox (a type of cable car) was used to bring the equipment down to sea level. The station was working again by 7:00 PM on 11 April 1944. It finally stopped operating on 28 January 1945.

For a while, the soldiers on Long Island were at the most advanced Allied position in the area. Brigadier General William F. Heavey, who commanded the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade, was surprised when the capture of the island was announced in December 1943. There were many rumors among the soldiers that the Japanese might try to take back the island. However, no such attempt was made. The Japanese accepted that they had lost their staging point.

The engineers built defenses, camp sites, and facilities for the radar station. They also built a small airstrip for light Piper Cub aircraft. It was 1,500 feet (457 meters) long and 50 feet (15 meters) wide, and they built it in just five days. Supplies came from Finschhafen using LCMs and sometimes PT boats. On 17 February 1944, the 592nd EBSR Group left Long Island. General Krueger praised the 592nd EBSR Group. He said they "accomplished its mission in the face of unusual odds" by being aggressive and skilled sailors.

|

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |