Lulu G. Stillman facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

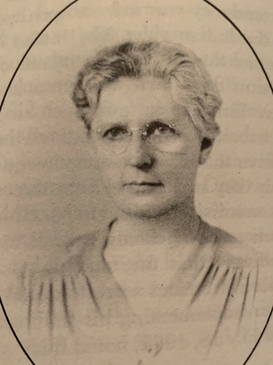

Lulu G. Stillman

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Lulu Glominski

1881/1882 Brooklyn, New York, US

|

| Died | July 4, 1969 (aged 87-88) Troy, New York, US

|

| Burial place | Oakwood Cemetery |

| Occupation | |

| Employer | Edward A. Everett |

| Organization | New York State Legislative Commission |

| Known for | Advocate for Native Americans |

|

Notable work

|

Everett report |

| Spouse(s) | Ernest E. Stillman (1904-1921) |

| Children | 1 |

Lulu G. Stillman (born 1881 or 1882 – died July 4, 1969) was an American who championed the rights of Native Americans. She worked as a stenographer, which means she typed very fast, and was also a researcher. She helped create the Everett report in the 1920s. This report stated that the Iroquois people had a legal right to 6,000,000 acres (2,400,000 ha) of land in New York. Even though the New York State government didn't accept the report, Lulu Stillman made sure it was saved.

Later, she became a strong supporter of the Iroquois Nation. She played a key role in stopping a law called the Indian Reorganization Act from being passed in New York.

Contents

Early Life and Work

Lulu Stillman was born in Brooklyn, New York. Her parents were Anthony and Louisa Glominski. Later in her life, she lived in Troy, New York.

From 1919 to 1922, Lulu Stillman worked for the Everett Commission. She was the main researcher and also the stenographer for Edward A. Everett. Historian Laurence M. Hauptman said that the "Everett report" was mostly Lulu Stillman's work.

The Everett Report

The Everett report found that the Iroquois people had a legal claim to 6,000,000 acres (2,400,000 ha) of land in New York. This claim was based on treaties signed in the late 1700s. A treaty is a formal agreement between groups, like nations.

The report was only signed by Edward Everett. It was never officially given to the state government and was not widely shared. Lulu Stillman typed a copy of all the commission's notes. She also saved copies of the report's findings. This was important because it meant the report wouldn't be lost.

Advocating for Native Americans

After the commission ended in 1922, Lulu Stillman kept working to support the Iroquois. In 1922, the Iroquois hired her to research an old agreement called the 1784 Treaty of Fort Stanwix. She became a spokesperson for the tribes and talked with different government groups.

In July 1934, the Tuscarora Nation welcomed her into their Beaver Clan. They gave her the name "Yon-dio-che-yoo," which means "true friend."

Opposing the Indian Reorganization Act

Lulu Stillman became a major critic of a person named John Collier and a law called the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934. She didn't trust the plans of either the New York state government or the federal government. Stillman believed that old treaties should be honored instead of creating new laws like the IRA.

On April 16, 1934, Stillman wrote an open letter to Iroquois leaders. In it, she warned them that the IRA might not truly help Native tribes. She also warned about plans that could make them lose their land and have to pay taxes. Historian Hauptman said that by the 1930s, Stillman was "the most respected outsider in Iroquois political circles." Her work, along with that of Alice Lee Jemison, helped stop the IRA from being passed in New York.

Preserving the Report

Also in 1934, a special assistant to the New York Attorney General met with Lulu Stillman. He then sent his nephew, James Griffith, to talk with her. Griffith made three copies of the Everett report that Stillman had saved. He added an introduction to them. Copies were sent to the United States Department of the Interior and the United States Department of Justice. However, these copies were lost or misplaced for many years. Lulu Stillman, though, carefully kept her copy and did not lend it out.

The Everett report was finally published in 1971, thanks to the copy that Lulu Stillman had preserved. She gave her papers to Helen Upton, who was researching the report and later wrote a book about it.

Personal Life

Lulu Stillman married Ernest E. Stillman, who was a dentist, around 1904. They had one daughter. She applied for a divorce in 1921. Lulu Stillman attended the Christ Methodist Church. She passed away in Troy on July 4, 1969. She was buried at Oakwood Cemetery.

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |