Mark Fuhrman facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mark Fuhrman

|

|

|---|---|

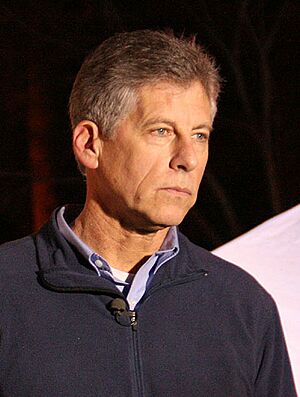

Fuhrman in 2008

|

|

| Born | February 5, 1952 Eatonville, Washington, U.S.

|

| Police career | |

| Current status | Retired |

| Department | |

| Country | |

| Years of service | 1975–1995 |

| Rank |

|

| Other work |

|

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1970–1975 |

| Rank | Sergeant |

Mark Fuhrman (born February 5, 1952) is a former American detective for the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD). He is best known for his role in the investigation of the 1994 murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman. This case led to the famous trial of O. J. Simpson.

In 1995, Fuhrman testified in court about finding important evidence, including a bloody glove at O. J. Simpson's home. During the trial, Simpson's lawyers said Fuhrman had used racist language in the past. Fuhrman denied this under oath. However, the defense team played secret recordings that proved he had used racist words many times.

This caused a major problem for the prosecution. The defense argued that Fuhrman was not a trustworthy witness and might have planted evidence because of his views. When asked in court if he had planted evidence, Fuhrman used his Fifth Amendment right to not answer. Many people believe this controversy is one of the reasons the jury found Simpson not guilty.

Fuhrman retired from the LAPD in 1995. A year later, he pleaded no contest to perjury (lying in court) for his false testimony about using racist words. Fuhrman has since apologized for his language and said he is not a racist. He has always maintained that he did not plant any evidence. Since leaving the police force, he has written books and hosted a radio show.

Contents

Early Life and Police Career

Mark Fuhrman was born in Eatonville, Washington. When he was 18, he joined the United States Marine Corps. He served during the Vietnam War era and reached the rank of sergeant before being honorably discharged in 1975. After his military service, he joined the Los Angeles Police Academy and became a police officer.

In 1985, Fuhrman responded to a domestic violence call involving O. J. Simpson and his wife, Nicole Brown Simpson. His report from that day later led to Simpson's arrest for spousal abuse. Fuhrman was promoted to detective in 1989. He served as a police officer for 20 years before retiring in 1995.

Role in the O. J. Simpson Murder Trial

Background of the Case

On the night of June 12, 1994, Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend Ron Goldman were murdered. Police officers arrived at the scene and found a bloody glove. Detective Fuhrman and his boss were the first detectives to arrive. Because Fuhrman knew about the past domestic violence call, he and other detectives went to O. J. Simpson's home.

At Simpson's house, Fuhrman found blood drops on Simpson's Ford Bronco car. He climbed over a wall to let the other detectives onto the property. They said they entered without a search warrant because they were worried Simpson might also be hurt.

Finding Key Evidence

While searching the property, Fuhrman found a second bloody glove. This glove appeared to be the matching pair to the one found at the murder scene. DNA testing later showed it had blood from both victims. This glove became one of the most important pieces of evidence against Simpson.

However, during the trial, Simpson was asked to try on the gloves, and they seemed too small for his hands. This moment created a lot of debate and doubt.

The Trial and Controversy

Simpson's defense team planned to argue that Fuhrman was a racist who planted the glove to frame Simpson. They brought up Fuhrman's past, including his use of racist language.

When Fuhrman was on the witness stand, defense lawyer F. Lee Bailey asked him if he had used a specific racial slur in the last 10 years. Fuhrman said no. To prove he was lying, the defense presented secret audio recordings. These were interviews Fuhrman had given to a writer between 1985 and 1994. On the tapes, Fuhrman used the slur many times.

The judge, Lance Ito, allowed the jury to hear parts of these tapes. After the tapes were revealed, the defense asked Fuhrman if he had ever planted evidence in the Simpson case. On his lawyer's advice, Fuhrman used his Fifth Amendment right not to answer, which can protect a person from incriminating themselves.

In his final speech to the jury, defense lawyer Johnnie Cochran called Fuhrman a "lying, perjuring, genocidal racist." He argued that Fuhrman's lie about his language meant he couldn't be trusted. This severely damaged the prosecution's case and is seen as a key reason why O. J. Simpson was acquitted.

Life After the Trial

The tapes made Fuhrman a very controversial figure. The focus of the trial seemed to shift from the murders to Fuhrman's actions and words. In 1996, he was charged with perjury for lying in court. He pleaded "no contest," which is similar to a guilty plea but without admitting guilt. He was sentenced to three years of probation and paid a fine.

Fuhrman later said he pleaded no contest because he could not afford a long trial and wanted to protect his family from more media attention. He has apologized for his racist language, calling it "immature, irresponsible ramblings." He has always insisted that he did not plant the glove or any other evidence.

Career as an Author

After retiring, Fuhrman moved to Idaho and began writing books. His first book was about the Simpson case. In it, he argued that the police and prosecution made several mistakes that weakened their case. For example, he said a bloody fingerprint found at the crime scene was not handled properly and was never presented as evidence in court.

Fuhrman has written several other books about famous crimes. One book, Murder in Greenwich, investigated the 1975 murder of Martha Moxley. His theory helped lead to the conviction of Michael Skakel, though the conviction was later overturned. He has also written about the assassination of John F. Kennedy and other cases.

Personal Life

Fuhrman has been married three times. He is known to be a collector of military medals and other historical items.