Michoacán–Guanajuato volcanic field facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Michoacán–Guanajuato volcanic field |

|

|---|---|

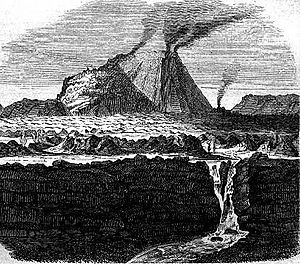

Parícutin cinder cone and the Cerro de Tancítaro shield volcano

|

|

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 3,860 m (12,660 ft) |

| Geography | |

| Location | Michoacán and Guanajuato, Mexico |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Cinder cones |

| Last eruption | 1943 to 1952 |

The Michoacán–Guanajuato volcanic field is a huge area in central Mexico. It is located in the states of Michoacán and Guanajuato. This area is not just one big volcano, but a place with many different kinds of volcanoes. You'll find lots of small, cone-shaped volcanoes called cinder cones, along with flatter, wider ones known as shield volcanoes, and even crater lakes called maars. The tallest point in this volcanic field is a peak called Pico de Tancítaro, which stands at 3,860 meters (about 12,664 feet) high.

This volcanic field is famous for two eruptions that happened not too long ago. One was the Jorullo volcano in the 1700s, and the other was the Parícutin volcano in the 1900s.

Contents

What the Volcanic Field Looks Like

The Michoacán–Guanajuato volcanic field covers a large area, about 200 by 250 kilometers (124 by 155 miles). It has about 1,400 different openings where lava or ash can come out, and most of these are cinder cones.

Cinder cones are the most common type of volcano here. They are usually small, cone-shaped hills. They form when volcanic ash and rock pieces pile up around a vent. These cinder cones are found at lower elevations, often on flat plains or on the sides of older, worn-down shield volcanoes. On average, there are about 2.5 cinder cones for every 100 square kilometers (38.6 square miles).

Shield volcanoes are much larger and wider, with gentle slopes that look like a warrior's shield lying on the ground. Most of the shield volcanoes in this field are very old, from a time called the Pleistocene epoch.

The field also includes maars. These are wide, low-relief volcanic craters that form when magma heats groundwater, causing a huge explosion. An example is Siete Luminarias, a group of seven maars near Valle de Santiago in Guanajuato. Other volcanoes in this field include Alberca de los Espinos and Cerro Culiacán.

Volcanic Eruptions

This volcanic field is known for two important eruptions that scientists have studied a lot.

The Jorullo Eruption (1759–1774)

The El Jorullo volcano started erupting on September 29, 1759. Before the eruption, people felt earthquakes in the area. Once the cinder cone began to erupt, it kept going for 15 years, finally stopping in 1774.

The eruption of El Jorullo destroyed a rich farming area. In just the first six weeks, the volcano grew about 820 feet (250 meters) tall from the ground! The early eruptions from El Jorullo mostly involved steam, mud, and water. They covered the area with sticky mudflows, water flows, and ash.

Later eruptions from El Jorullo were different; they mainly produced lava and ash, without the mud or water. This 15-year eruption was the longest one El Jorullo has ever had, and it was also the longest known cinder cone eruption in history. You can still see the lava flows to the north and west of the volcano today. This eruption was quite powerful, rated as a VEI 4 (Volcanic Explosivity Index).

Today, El Jorullo is about 1,320 meters (4,330 feet) high. Its crater is about 1,300 by 1,640 feet (400 by 500 meters) wide and 490 feet (150 meters) deep. El Jorullo also has four smaller cinder cones that grew on its sides.

The Parícutin Eruption (1943–1952)

The Parícutin volcano began in a very unusual way. On February 20, 1943, a farmer named Dionisio Pulido was plowing his cornfield. Suddenly, a crack opened in the ground, and ash and stones started shooting out! Pulido, his wife, and their son all saw the beginning of this new volcano.

El Parícutin grew incredibly fast. In just one week, it was as tall as a five-story building. Within a month, people could see it from far away. Most of the volcano's growth happened in its first year, when it was in an explosive phase, sending out hot ash and rocks called pyroclastic flows.

The nearby villages of Paricutín (which gave the volcano its name) and San Juan Parangaricutiro were buried by lava and ash. The people living there had to move to new homes.

After about a year, the cinder cone had grown to 336 meters (1,102 feet) tall. For the next eight years, El Parícutin continued to erupt, but mostly with quieter lava flows. These flows scorched about 25 square kilometers (9.6 square miles) of land around the volcano. The volcano's activity slowly decreased until its last six months, when it became violent and explosive again.

In 1952, the eruption finally ended, and Parícutin became quiet. It reached a final height of 424 meters (1,391 feet) from the cornfield where it began. Like most cinder cones, Parícutin is believed to be a monogenetic volcano. This means that once it has finished erupting, it will never erupt again. If new eruptions happen in the Michoacán–Guanajuato volcanic field, they will start in a completely new location.

Sadly, three people died during the Parícutin eruption because of lightning strikes caused by the volcanic activity. However, no one died directly from the lava or from breathing in the ash.

Gallery

See also

In Spanish: Campo volcánico Michoacán - Guanajuato para niños

In Spanish: Campo volcánico Michoacán - Guanajuato para niños

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |