Moral responsibility facts for kids

In philosophy, moral responsibility is about whether someone deserves praise, blame, rewards, or punishment for their actions. It's about whether they followed their moral obligations, which are like rules for what's right and wrong.

Deciding what counts as "morally right" or "morally wrong" is a big part of ethics, which is the study of moral principles. People who can be held morally responsible for their actions are called moral agents. These agents can think about their situation, decide what they want to do, and then do it.

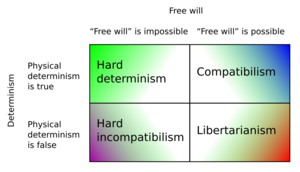

The idea of free will is very important here. Free will means you have the power to choose your own actions. If you have free will, are you always responsible for what you do? Some philosophers, called incompatibilists, believe that if everything is already decided (this is called determinism), then you can't have free will. But others, called compatibilists, think that free will and determinism can both exist at the same time.

Moral responsibility is not always the same as legal responsibility. Legal responsibility means the law can punish you for something. Sometimes, if you're morally responsible for an act, you're also legally responsible. But not always!

Many people, like parents, teachers, and politicians, talk about "personal responsibility." This means taking charge of your own actions and choices.

Contents

Understanding Moral Responsibility

Philosophers have different ideas about moral responsibility, depending on how they see free will.

Do We Have Free Will?

Some philosophers, called Metaphysical libertarians, believe that our actions are not always caused by things that happened before. They think we truly have free will, which means we can choose differently. Because of this, they believe we can be morally responsible. They often feel that if we couldn't have acted differently, we wouldn't be responsible.

It often feels like we could have chosen differently in our daily lives. This feeling doesn't prove free will exists, but some thinkers say it's a necessary part of having free will.

Jean-Paul Sartre suggested that people sometimes try to avoid blame by saying their actions were "determined." He said we might hide behind the idea of determinism if our freedom feels too heavy or if we need an excuse.

Another idea is that a person's moral responsibility comes from their character. For example, someone with a "bad character" might be punished because it's right to punish those who are bad, even if their character led them to act a certain way.

In law, there are times when people are not held fully responsible, like with the insanity defense. This defense argues that a person's actions were due to unusual brain function, not a "guilty mind." This suggests that brain function can influence our choices.

The Luck Argument

The "argument from luck" challenges the idea of free will. It suggests that our actions, and even our character, are shaped by many things outside our control. So, it might not be fair to hold someone entirely responsible. Thomas Nagel pointed out that different types of luck, like our genes or things that happen to us, affect how our actions are judged morally.

If our actions are random or probabilistic, it's hard to praise or blame someone for something that just happened by chance in their brain.

Is Everything Decided?

Hard determinists believe that everything that happens, including our choices, is already decided by things that came before. They think that if determinism is true, then we don't have free will in the way most people imagine. Some even say, "Too bad for free will!"

A famous lawyer, Clarence Darrow, used this idea to defend his clients. He argued that they were shaped by their parents and surroundings, and didn't "make themselves." So, they shouldn't be forced to pay for things they couldn't control.

Researchers like Joshua Greene and Jonathan Cohen, who study the brain and ethics, suggest that our idea of moral responsibility is based on the belief that we have free will. But they argue that brain research shows our brains are responsible for our actions, not just in cases of mental illness, but in everyday situations too. For example, damage to the front part of the brain can make it harder to make good decisions and might lead to violent behavior. This is true for people with brain injuries, teenagers (whose brains are still developing), and even children who have been neglected.

Greene and Cohen predict that as we learn more about the brain, people's ideas about free will and moral responsibility will change. They also say that our legal system doesn't need the idea of free will to work. Instead of just punishing people (which is called "retribution"), the legal system can focus on making society better and preventing future harm.

Neuroscientist David Eagleman agrees. He thinks the legal system should look to the future. Instead of asking only who is to blame, we should focus on what needs to change in a person's behavior and brain. Eagleman says it's wrong to think a person can make a decision completely separate from their body and past experiences. He also points out that less attractive people and minorities often get longer sentences, which he sees as a sign that the legal system needs more science.

No Free Will, No Determinism?

Derk Pereboom has a view called hard incompatibilism. He thinks we can't have free will if our actions are determined by things we can't control, or if they just happen by chance. He believes that the kind of free will needed for true praise and blame, or punishment and reward, probably doesn't exist.

However, Pereboom also says that we can still hold people responsible in ways that look to the future. For example, if someone acts badly, we can still blame them to help them improve, fix relationships, or protect others.

He suggests that our justice system can work without needing to blame people in the traditional sense. We can still keep dangerous people away from others, like quarantining someone with a dangerous illness, to protect society. And just as we try to cure sick people, we should try to help criminals get better and rejoin society.

Can Both Be True?

Compatibilism is the idea that we can have free will even if determinism is true. The ancient Hindu text, Bhagavad Gita, has an early compatibilist idea. It says that natural forces create actions, and it's only our pride that makes us think we are fully in charge. But it also says that if we understand how nature works, we won't be its slave. This means being aware of the bigger picture helps us be better moral agents.

Baruch Spinoza, a Western philosopher, had a similar idea. He wrote that people think they are free because they are aware of their desires, but they don't know the hidden causes behind those desires. Both the Bhagavad Gita and Spinoza suggest that understanding ourselves and controlling our emotions can help us follow our true nature.

P.F. Strawson is a modern compatibilist who argued that our "reactive attitudes" (like resentment or gratitude) show that we naturally hold people responsible, even if determinism is true.

Other Ideas on Responsibility

Daniel Dennett wonders why we care so much about moral responsibility. He suggests it might just be a deep, philosophical desire.

Bruce Waller argues that moral responsibility is like "ghosts and gods" and doesn't fit in a world without miracles. He believes we can't truly punish someone because their actions are influenced by luck, genes, and environment—things they can't control. Waller tries to "rescue" free will from moral responsibility, meaning he thinks we can still have free will even if we aren't morally responsible in the traditional sense.

Knowing What You're Doing

For someone to be morally responsible, two things are usually needed:

- Control: Did the person have free will to do the action? (This is what we talked about above.)

- Knowledge: Was the person aware of what they were doing and its moral importance?

Most philosophers agree that you need to be "aware" of four things to be morally responsible:

- The action you are doing.

- Its moral meaning (is it right or wrong?).

- The results of your action.

- Other choices you could have made.

Experiments on Responsibility

Scientists have studied whether people naturally think free will and determinism can exist together. Some studies have looked at different cultures. The results are mixed:

- When people are asked general questions about responsibility and determinism, they often say that if someone couldn't have done otherwise, they aren't responsible.

- But when people are given a specific example of a bad act, they often say the person is responsible, even if the act was determined.

Research into how the brain works also tries to understand free will.

Group Responsibility

Usually, we think of individuals as being morally responsible. But sometimes, groups of people can have "collective moral responsibility." For example, a company or a government might be held responsible for something bad that happened. During apartheid in South Africa, the government was seen as having collective moral responsibility for violating the rights of many people.

Psychopathy and Responsibility

One characteristic of psychopathy is that people with it often "fail to accept responsibility for their own actions."

Can Robots Be Responsible?

With the rise of robots and smart systems, a new question comes up: Can an artificial system be morally responsible? And if so, when does responsibility shift from the human creators to the system itself? This is different from machine ethics, which is about how artificial systems should behave morally.

Why Robots Might Not Be Responsible

Some argue that robots can't be morally responsible because they don't have intentions or feelings like humans do.

- Arthur Kuflik said that humans must always be ultimately responsible for a computer's decisions, because humans design and program them.

- Others argue that if a machine's rules are fixed or entirely given by humans, it can't be truly responsible. They say that current artificial systems have zero responsibility for their actions; it all falls on the humans who created and programmed them.

Why Robots Might Be Responsible

Some argue that artificial systems could be morally responsible if their behavior is so similar to a moral person that you can't tell the difference.

- Andreas Matthias talked about a "responsibility gap." He said it would be unfair to always blame humans for a machine's actions, but blaming the machine is also new. He suggested that machines might be responsible in three cases:

- Modern machines can be unpredictable, but they do important tasks that simpler methods can't handle.

- There are many "layers" between the creators and the system, especially as programs become more complex.

- Systems can change their own rules while they are working.

See also

In Spanish: Responsabilidad moral para niños

In Spanish: Responsabilidad moral para niños

- Ability

- Accountability

- Declaration of Human Duties and Responsibilities

- House of Responsibility

- Incompatibilism

- Legal liability

- Moral agency

- Moral hazard

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |