Moving Day (New York City) facts for kids

Imagine a day when almost everyone in a huge city like New York City had to move house at the exact same time! This was a real tradition called Moving Day. It started way back when New York was just a group of colonies and continued until after World War II.

Here's how it worked: On February 1st, landlords would tell tenants how much rent would be for the next year. Then, people would spend the spring looking for new homes and good deals. But the big day was May 1. On this day, all housing leases in the city ended at 9:00 AM. This meant thousands of people had to pack up and move all at once!

Some people say this tradition started because the first Dutch settlers arrived in Manhattan on May 1st. Others think it came from the English celebration of May Day. What began as a custom became a rule in 1820. A law said that if no other date was set, all housing contracts ended on May 1st. If May 1st was a Sunday, the deadline moved to May 2nd.

Contents

A Look Back: The History of Moving Day

Early Days and Growing Chaos

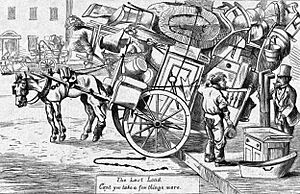

In 1799, someone noticed that New Yorkers seemed to go a little "mad" on May 1st. They just couldn't rest until they had moved! There weren't enough professional movers (called "cartmen") for everyone. So, farmers from nearby areas like Long Island and New Jersey would come with their wagons. They would charge high prices to help people move their belongings.

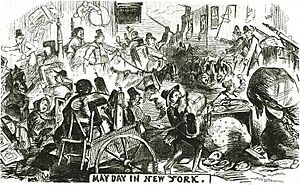

By 1820, Moving Day was total "pandemonium." This means it was super chaotic! The streets were jammed with wagons carrying furniture and household items. It was like a giant traffic jam of moving trucks. In 1848, a group called the Tenant League complained that Moving Day was just a way for landlords to raise rents every year. Moving was also expensive. Cartmen sometimes charged more than the city allowed. People might pay a whole week's wages just to move their stuff! If you didn't pay, the cartman might even take your belongings to the police station!

Changes Over Time

By 1856, the strict rule of Moving Day started to change a bit. Some people began moving a few days before or after May 1st. This created a "moving week" instead of just one day. After an economic downturn in 1873, more homes were built. This made housing cheaper, so people didn't need to move as often.

Later in the 1800s, many New Yorkers started leaving the city for cooler suburbs during the hot summer. When they returned, October 1 became a second Moving Day. People would get their things out of storage and move into new homes. This October date might be linked to an old English custom of paying rent on September 29th. Eventually, the October date became more popular than the May date. By 1922, moving companies reported only a "moderate flurry" of activity in the spring. Movers even tried to get a law passed to spread out the fall rush over three dates: September 1st, October 1st, and November 1st. Over time, the idea of a specific Moving Day slowly disappeared. Today, some business leases still end on May 1st or October 1st.

The End of a Tradition

At its busiest, in the early 1900s, it's thought that a million people in New York City moved on the same day! People tried to resist Moving Day in the 1920s and 1930s. But it was World War II that finally ended the tradition. Moving companies couldn't find enough strong workers because so many men were away fighting. After the war, there weren't enough homes, and rent control laws were put in place. These changes finally stopped Moving Day for good. By 1945, a newspaper headline announced: "Housing Shortage Erases Moving Day."

Life on Moving Day: What It Was Like

Imagine the streets of New York City on Moving Day! It was a wild scene. English writer Frances Trollope described it in 1832. She said the city looked like people were running from a plague! Every street was filled with furniture, carts, wagons, ropes, and straw. Movers of all backgrounds were everywhere. Everyone she spoke to hated the custom, but they said it couldn't be avoided if you rented a house. Many of her friends even bought or built homes just to avoid this yearly hassle!

John Pintard, who helped start the New-York Historical Society, wrote about Moving Day in a letter. He said the streets were crowded with overloaded carts and hand barrows. It was hard to even walk on the sidewalks! He mentioned that the practice seemed "absurd" to outsiders.

Even the famous frontiersman Davy Crockett saw Moving Day in 1834. He said it looked like the city was "flying before some awful calamity." He thought it seemed like a "frolic," as if people were changing houses just for fun! He was amazed that people moved every year, unlike him in his log cabin.

An Englishwoman named "Mrs. Felton" wrote in 1843 that carts loaded with furniture raced through the city. It looked like people were "flying from a pestilence."

The New York Times wrote about Moving Day in 1855. They said it would start early and last late. Sidewalks would be blocked. Old beds and fancy pianos would be mixed together. Everything would be a mess! Mirrors might break, and furniture would get scratched. Family pictures would be ruined. Houses would be super dirty. The newspaper told people to keep their tempers and not argue with the movers. They also said that a few nails, some glue, and varnish could fix many of the damaged items.

George Templeton Strong, a New York lawyer, wrote in his diary that the city was in a "chaotic state." He said every other house seemed to be emptying into the street. Sidewalks were covered with furniture. Streets were filled with long lines of carts and wagons. He joked that people hadn't moved past the "nomadic" stage of civilization!

In 1865, the Times described the attitude of the "carmen" (movers) on Moving Day. They were usually not very polite, but on Moving Day, they were even worse! They became "lord of the ascendant," meaning they were in charge. They would laugh at offers of $5 to move a load a few blocks. They didn't want to make plans ahead of time. They acted like they preferred to be left alone, but they were always looking for the best deal. Once hired, they worked with total indifference. The newspaper said they were "above all ordinances" on that day!

Lydia Maria Child, an editor of an anti-slavery newspaper, also described Moving Day. She said all of New York moved on May 1st. Streets were full of loaded wagons with tables dancing and carpets rolling. Small chairs would tumble off beds and break apart. Children carried flower pots or oil cans, focused on their important tasks. Dogs seemed confused, and cats sat on doorsteps, meowing sadly. She felt it was a symbol of America's constant change. She even told a story about a lady who closed her blinds on May Day. When asked if she'd been in the country, she said, "I was ashamed not to be moving... and so I shut up the house that the neighbours might not know it." This shows how strong the custom was!

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |