New York City teachers' strike of 1968 facts for kids

The New York City teachers' strike of 1968 was a big disagreement that lasted for months. It happened between a new school board, run by the community in the mostly Black neighborhoods of Ocean Hill and Brownsville in Brooklyn, and New York City's United Federation of Teachers (UFT).

The conflict started with a short protest in the Ocean Hill-Brownsville school district. It grew into a citywide strike in September 1968. This strike closed public schools for a total of 36 days. It also made tensions between Black and Jewish communities much worse.

Thousands of teachers went on strike because the new community-controlled school board transferred some teachers and school leaders. This was a normal practice, but these workers were mostly white or Jewish. The United Federation of Teachers (UFT), led by Albert Shanker, demanded that these teachers be allowed to return to their jobs. The union also accused the school board of being against Jewish people.

The strike showed a big conflict between a community's right to control its local schools and teachers' rights as workers. Even though the school district was small, its outcome was very important. It could have changed the entire education system in New York City and beyond.

Contents

Why the Strike Happened

Brownsville's Story

From the 1880s to the 1960s, Brownsville was mainly a Jewish neighborhood. Many people there supported unions and workers' rights.

Around 1940, Black people made up a small part of Brownsville's population. This number doubled in the next ten years. Most new residents were poor and lived in less desirable housing. Even though the neighborhood was separated by race, Black and Jewish people often mixed more here than in other places.

By 1960, the neighborhood changed quickly. Many Jewish families moved out, often looking for better opportunities. More Black and some Latino families moved in. By 1970, Brownsville was mostly Black and Puerto Rican. The neighborhood had few community centers or job opportunities.

Schools in Brownsville

Even after the Supreme Court's 1954 Brown v. Board ruling against segregated schools, schools in Brooklyn actually became more separated by race. This happened because of how school districts were drawn and where new schools were built.

Before the strike, Brownsville's schools were very crowded. Students even attended in different shifts. Junior High School 271, which became central to the strike, was built in 1963. This school's performance was low from the start. Most students tested below their grade level in reading and math. Few students went on to the city's top high schools.

New York City's school system was controlled by a large, central office. Activists in the 1960s felt this office was not interested in truly integrating schools. This frustration led them to push for community control instead of just desegregation.

The Teachers' Union

Teachers in Brownsville belonged to the United Federation of Teachers (UFT). This union believed that different cultures could exist together in a democratic society. The UFT also valued individual achievement. Many members of the UFT were Jewish.

The number of teachers joining unions grew a lot in the 1960s. Teacher strikes also became more common.

In 1964, civil rights leaders organized a citywide protest against school segregation. They asked the UFT to join, but the union refused. They only promised to protect teachers who participated. Over 400,000 New Yorkers joined the one-day protest. It was the largest civil rights demonstration in American history. However, the UFT later refused to defend teachers who joined a second protest. This made some Black community leaders feel that an alliance between the union and the Black community was not possible.

Black Teachers and Schools

The UFT had a program for schools with many Black students called "More Effective Schools." This program aimed to make class sizes smaller. However, the African-American Teachers Association (ATA) challenged this program. The ATA felt that New York City's schools had a system of racism. In 1966, the ATA began campaigning for community control of schools.

In 1967, the ATA disagreed with the UFT over a rule that allowed teachers to remove "disruptive" children from classrooms. The ATA argued this rule made racism worse. In the fall of 1967, the UFT went on a two-week strike to get this rule approved. Most ATA members left the union.

Community Control of Schools

In the New York City school system, only 8% of teachers and 3% of school leaders were Black. After the Brown v. Board ruling, some students from Ocean Hill–Brownsville were bused to white schools. They often felt they were treated unfairly. Trust in the school system kept getting lower.

Inspired by the civil rights movement, but frustrated by the slow pace of desegregation, African Americans started demanding control over the schools where their children learned. The ATA called for community-controlled schools that would teach with a "Black value system." This system would focus on "unity" and "collective work."

Mayor John Lindsay and some wealthy business leaders supported community control. They hoped it would bring social stability. In 1967, a report suggested trying to give more power to local communities. The city decided to try this in three areas, including Ocean Hill–Brownsville.

The New York City Board of Education made Ocean Hill–Brownsville one of these new, decentralized school districts. In July 1967, the district received a grant to help it operate. The new district had a community-elected board that could hire school leaders. If successful, this experiment could have led to citywide decentralization. The local Black community saw this as a way to gain power against a large, white-run system. However, the teachers' union saw it as a way to weaken unions. They worried they would have to deal with many small local groups instead of one central administration.

Rhody McCoy became the new superintendent of the Ocean Hill–Brownsville board. He had worked in the city's public school system since 1949. He was known for wanting to change schools for children who were often overlooked.

School Changes

The new school administration made some changes to the curriculum. They expanded the role of Black and African history and culture. Some schools began teaching the Swahili language. One school with many Puerto Rican students became completely bilingual.

Reports on the 1967–1968 school year were generally positive. Visitors, students, and parents who supported the schools liked the shift to student-focused education. However, the district still relied on the central school board for money. Many of its requests, like for telephones or new library books, were reportedly met very slowly.

Teachers were surprised by how much control the new school board had. Many did not like the board's new rules about staff and what was taught. The UFT did not approve of the new principals. They also criticized the Ocean Hill–Brownsville curriculum.

Staffing Decisions

The new administration in Ocean Hill–Brownsville began choosing principals from outside the usual approved list. They appointed five new principals from different racial backgrounds, including New York City's first Puerto Rican principal. This was popular with the community but angered some teachers.

In April 1968, the administration asked for more control over staff, money, and curriculum. When the city did not grant these powers, parents in the district started a school boycott. This happened around the same time as unrest following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

On May 9, 1968, the administration asked for 13 teachers and 6 administrators to be transferred from Junior High School 271. The board accused these workers of trying to harm the project. They all received short letters saying their employment was ending immediately. This decision went against the union's contract rules. Most of the teachers on the list were Jewish. One Black teacher on the list, seemingly by mistake, was quickly allowed to return. In total, 83 workers were dismissed from the district.

Parents in Brownsville generally supported the school board's decision. People outside the community also appreciated the Black school board's effort to take control of its own schools.

Albert Shanker called the dismissals "vigilante activity." He said the schools did not follow proper procedures. The Board of Education told the teachers to ignore the letters. Mayor John Lindsay also spoke out against the district's decision.

The Strikes Begin

May Protests

When the teachers tried to go back to school, hundreds of community members and teachers who supported the administration blocked them. One sign in the school said, "Black people control your schools."

On May 15, 300 police officers came to the school. They blocked off the area, allowing the teachers to return. The city's Board of Education and the Ocean Hill–Brownsville board both announced that the schools would close that same day.

From May 22–24, 350 UFT members stayed out of school to protest. On June 20, these 350 striking teachers were also dismissed by the governing board. They were then returned to the control of the New York City public school system.

Citywide Strikes

A series of citywide strikes began at the start of the 1968 school year. These strikes closed public schools for a total of 36 days. The union went on strike even though a new law, the Taylor Law, made it illegal. More than a million students could not attend school during these strike days.

On September 9, 93% of the city's 58,000 teachers walked out. They agreed to return two days later after the Board of Education ordered the dismissed teachers to be reinstated. But they walked out again on September 13, when it became clear that the Board could not make this decision happen.

Reactions to the Strike

Black Community Leaders

The NAACP supported the strike. This was notable because community control was different from their usual goal of integration.

Some Black leaders, like Bayard Rustin and A. Philip Randolph, also supported the strike. They were well-known in the labor movement and the civil rights movement. However, they faced criticism from parts of the Black community for their stance.

Disagreement Within the UFT

Not all UFT teachers supported the strike. Some actively opposed it. A study in 1974 found that teachers of Black students, both white and Black, were more likely to oppose the strike. A group of Black and Puerto Rican UFT members, supported by other unions, spoke out against the strike and supported Ocean Hill–Brownsville.

Immediate Effects

On Schools

In Ocean Hill–Brownsville

Students and teachers returned to a difficult situation in the fall. Classes were held even with UFT picket lines outside.

Schools in Ocean Hill–Brownsville ran more smoothly than in other places. This was because they were less dependent on the striking teachers. The board hired new teachers to replace those on strike. Many of these new hires were local Jewish people, to show the district was not against Jewish people.

When the original teachers were allowed back at JHS 271, students refused to attend their classes. The New York School Superintendent tried to close schools in the district and remove Rhody McCoy and most of the principals. When they refused to leave, the police were called. The returning teachers were told to meet with McCoy. When they arrived, they faced threats and some objects were thrown.

In New York City Schools

Striking teachers were in and out of school during the first weeks of the year. This affected over one million students.

Superintendent Donovan ordered many schools locked. In many places, people broke windows and locks to get back into their school buildings. Some even camped overnight at schools to prevent further lockouts by janitors.

Some parents sent their children to Ocean Hill–Brownsville because those schools were open. Most of these students were Black, but some were white. Some traveled long distances to attend the community-controlled schools.

Racism and Antisemitism

Albert Shanker was often called a racist. Many African Americans accused the UFT of being controlled by Jewish people. A Puerto Rican group in Ocean Hill–Brownsville even burned Shanker's image in protest.

Shanker and some Jewish groups said the original firing of teachers was due to antisemitism (prejudice against Jewish people). During the strike, the UFT shared a pamphlet that criticized a lesson advocating Black separatism. Shanker also distributed a pamphlet that some of his members found.

An incident on a radio station further divided the Black and Jewish communities. A teacher read a student's poem that contained hateful language towards Jewish people. The union filed a complaint, and the incident caused more tension.

Some people, including the New York Civil Liberties Union, accused Shanker of exaggerating antisemitism to gain sympathy.

How the Strike Ended

The strike ended on November 17. The New York State Education Commissioner took control of the Ocean Hill–Brownsville district. The teachers who had been dismissed were allowed to return to their jobs. Three of the new principals were transferred. The district was run by a temporary leadership for four months.

The conflict in Ocean Hill–Brownsville continued even after the strike ended. In 1969, some people claimed there was a "purge" of Black teachers. When school opened in September 1969, the school district closed itself for a day to protest new rules that took away its independence.

What Happened Next

In the weeks after the strike, there was still hostility between the returning teachers and the students and replacement teachers.

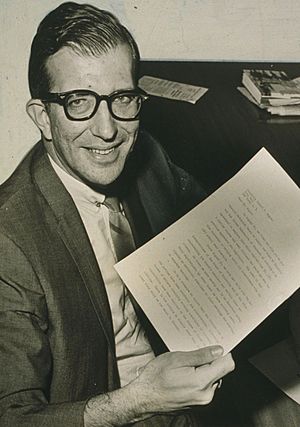

Albert Shanker became a nationally known figure after the strike. He was jailed for 15 days in February 1969 for allowing the strikes, which went against New York's Taylor Law. The Ocean Hill–Brownsville district lost direct control over its schools. Other districts never gained control over their schools.

The UFT weakened the ATA in the 1970s with a lawsuit. They accused the ATA of excluding white teachers. The UFT also tried to cut off the ATA's money and remove its leaders from the school system.

Residents of Brownsville continued to feel ignored by the city. In 1970, some protested in what were called the "Brownsville Trash Riots." When schools agreed to use a standardized reading test in 1971, scores had fallen.

The strike deeply divided New York City. It became known as one of Mayor John Lindsay's "Ten Plagues." Many experts agree that "the whole alliance of liberals, blacks and Jews broke apart on this issue." The strike created a serious split between white liberals, who supported the teachers' union, and Black people, who wanted community control. It showed that these groups, who had worked together in the Civil Rights Movement and the labor movement, could sometimes have conflicts.

Some groups involved in civil rights and Black liberation movements started creating independent African schools. These events also pushed New York's Jewish population to see themselves more as "white," which further increased racial tensions in the city. The events surrounding the strike were a factor in the decision by Meir Kahane to form the Jewish Defense League.

Images for kids

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |