New York ex rel. Cutler v. Dibble facts for kids

Quick facts for kids New York ex rel. Cutler v. Dibble |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Decided December 30, 1858 | |

| Full case name | People of State of New York ex rel. Asa Cutler, John Underhill, and Arza Underhill v. Edgar C. Dibble, County Judge of Genesee County |

| Citations | 62 U.S. 366 (more)

21 How. 366, 16 L. Ed. 149; 1858 U.S. LEXIS 653

|

| Prior history | 18 Barb. 412 (N.Y. Sup. Gen. Term 1854), aff'd,16 N.Y. (2 E.P. Smith) 203 (1854) |

| Holding | |

| The New York nonintercourse act does not violate the Indian Commerce Clause, the federal Nonintercourse Act or the Treaty of Buffalo Creek | |

| Court membership | |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Grier |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 3; Nonintercourse Act; Treaty of Buffalo Creek | |

New York ex rel. Cutler v. Dibble was a United States Supreme Court case decided in 1858. It was closely related to another important case called Fellows v. Blacksmith (1857).

This case was about the Seneca tribe and their land in New York. The Seneca tribe used a New York state law to remove the Ogden Land Company and its buyers from their lands. The company and buyers argued that the state law was against federal laws and treaties.

Usually, Native American tribes would use federal laws to protect their land. But in this case, the Seneca tribe used a state law. This made the case quite unique for its time.

Contents

How the Land Dispute Started

The Treaty of Buffalo Creek (1838) was an agreement that said the Seneca people would move to what is now Kansas. Their land in New York was supposed to go to the Ogden Land Company.

However, the Tonawanda Band of Seneca Indians, who lived on the Tonawanda Reservation, disagreed with this treaty. They said that none of their leaders (called sachems) had signed it.

A Seneca leader named Ely S. Parker hired a lawyer, John H. Martindale, to help. Martindale filed four lawsuits against the Ogden Land Company.

- The first two lawsuits did not succeed in the New York courts.

- The third lawsuit, Fellows v. Blacksmith (1857), was successful in both the New York Court of Appeals and the U.S. Supreme Court.

- The fourth lawsuit was New York ex rel. Cutler v. Dibble. The New York Court of Appeals had sided with the Seneca tribe, and the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear the case.

The New York Law and Early Court Decisions

The case began when the local district attorney in Genesee County, New York sued on behalf of the Seneca people. They sued Asa Cutler, John Underhill, and Arza Underhill. The lawsuit was based on a New York state law from March 31, 1821.

This 1821 law made it illegal for anyone who was not Native American to live on or settle on lands belonging to Native American tribes in New York. The law also said that any agreements allowing non-Native Americans to live on these lands were completely invalid.

If someone broke this law, a county judge could issue a warrant. This warrant would tell the sheriff to remove the person and their family from the land within ten days.

The people being sued (Cutler, Underhill, and Underhill) claimed they had a right to the land because of the Treaty of Buffalo Creek. They also asked for a jury trial.

- The county court decided in favor of the Seneca people.

- The case then moved to the New York Supreme Court. This court heard a lot of evidence. It stated that the Seneca nation had not properly given their land to Ogden and Fellows. However, the U.S. Supreme Court later said this specific point was not important for their decision.

- The New York Court of Appeals agreed with the lower courts. It ruled that the 1821 New York law did not go against the New York Constitution. This meant the defendants did not have a right to a jury trial based on property rights.

After these decisions, the case was sent to the U.S. Supreme Court for review.

The Supreme Court's Decision

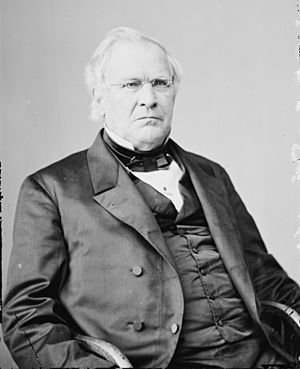

Justice Robert Cooper Grier wrote the opinion for the U.S. Supreme Court. All the judges agreed with the decision. The Court upheld the ruling of the New York Court of Appeals.

The Supreme Court focused on whether the New York state law and its actions went against any federal laws. Specifically, they looked at:

- The Indian Commerce Clause of the United States Constitution.

- The federal Nonintercourse Act.

- The Treaty of Buffalo Creek between the U.S. government and the Senecas.

State Law is Constitutional

The Court decided that the New York state law was a proper use of the state's `police power`. This means the state had the right to make laws to protect the safety and well-being of its people.

The Court explained that the law was a way to protect Native Americans from people moving onto their land without permission. It also helped keep the peace. The Court said that even though Native American nations have a special relationship with the U.S. government, the state of New York still had power over their people and property. This power was needed to keep the peace and protect these groups from being taken advantage of. The Court stated that a state's power to make such rules for peace is absolute and had not been given up. Therefore, the New York law did not go against the U.S. Constitution.

No Conflict with Federal Law

The Court also found that the New York law did not go against any federal laws. They said there was no federal law that allowed white people to move onto Native American lands without permission.

Treaty Not Violated

Finally, the Court ruled that the New York law did not violate the Treaty of Buffalo Creek. The Court referred to its earlier decision in Fellows v. Blacksmith (1856). In that case, the Court had said that the Seneca people could only be removed from their land by the federal government, and only when the government decided it was time.

The Court explained that if the U.S. government had already moved the Seneca people and given the land to the buyers, then the New York law would be a problem. But the Seneca people, specifically the Tonawanda band, were still peacefully living on their land and had not been removed by the U.S. government.

Therefore, the people claiming the land under Ogden and Fellows did not have the right to simply move onto the land or force the Seneca people out. This New York law did not affect their claim to ownership. It only meant that as long as the Native Americans were in peaceful possession of their land, the state law protected them from non-Native American intruders.

The Court emphasized the important relationship of trust between the federal government and Native American tribes. It stated that Native Americans were to be moved to new homes by their guardians, the United States. They could not be forced out by individuals who claimed to have bought their land, or even by courts. Until the U.S. government stepped in to remove them, the Seneca people and their lands were protected by New York laws from people trying to move onto their land.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |