New York shirtwaist strike of 1909 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids New York Shirtwaist Strike of 1909(Uprising of the 20,000) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

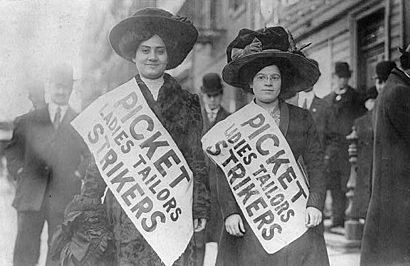

Two women strikers picketing during the strike

|

|||

| Date | November 1909–March 1910 | ||

| Location | |||

| Resulted in | Successful renegotiation of garment worker contracts | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | 5 | ||

| Injuries | 104 | ||

| Charged | 10% | ||

| Fined | 4.5$ | ||

The New York shirtwaist strike of 1909 was a big worker protest. It was also called the Uprising of the 20,000. Most of the workers were young Jewish women. They worked in New York City factories making shirtwaists (blouses). This was the largest strike ever by American women workers at that time.

The strike started in November 1909. It was led by Clara Lemlich and the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union. The National Women's Trade Union League of America (NWTUL) also helped. In February 1910, the workers and factory owners reached an agreement. The workers got better pay, working conditions, and shorter hours.

About a year after the strike, the terrible Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire happened. This fire showed how dangerous and difficult working conditions were for immigrant women.

Contents

Working Conditions Before the Strike

In the early 1900s, many factory workers in America faced very poor conditions. This was especially true for women making clothes. Their workplaces were often crowded and dirty. They worked very long hours for very low pay.

New York City was a major center for making clothes. About 30,000 people worked in 600 shops and factories. They made clothes worth about $50 million each year.

Low Pay and Long Hours

Women workers often got stuck in a system where they earned very little. Many were called "learners," even if they had some skills. These "learners" might earn only $3 or $4 a week. More skilled workers, usually men, earned $7 to $12 a week. The most skilled jobs, like cutting fabric, were almost always done by men.

Many garment workers worked in small, crowded places called sweatshops. A normal work week was 65 hours. During busy times, it could be as long as 75 hours. Even with low pay, workers often had to buy their own needles, thread, and even sewing machines. They could be fined if they were late or if they damaged a piece of clothing.

At some factories, like the Triangle Shirtwaist Company, steel doors were used to lock workers inside. This was to stop them from taking breaks. Women had to ask permission just to use the restroom.

Immigrant Workers

Most of the workers in the clothing industry were immigrants. About half were Yiddish-speaking Jews. About one-third were Italians. Around 70% of the workers were women. About half of these women were under 20 years old.

In shirtwaist factories, almost all the workers were Jewish women. Some of them had been part of worker unions in Europe. Many Jewish women had been members of the Bund. This meant they knew about organized labor and how to protest. These Jewish women were also strong supporters of women's suffrage (the right to vote) in New York.

The Strike Begins

In September 1909, workers at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory went on strike. On November 22, 1909, a big meeting was held at the Great Hall of Cooper Union. The International Ladies Garment Workers Union organized this meeting. At the meeting, workers voted to start a general strike.

Clara Lemlich, a 23-year-old garment worker from Ukraine, was at the meeting. She was already on strike. She had even been hurt by hired toughs while protesting. At the meeting, men were talking for hours about why a general strike might be a bad idea. Clara had heard enough. She stood up and said in Yiddish, "I have no further patience for talk. I move we go on a general strike!”

Her words received a huge cheer from the crowd. Clara then made a promise. She swore that if she ever betrayed the cause, her hand would wither.

The Uprising of the 20,000

On November 24, just one day after the strike was called, 15,000 shirtwaist workers walked out of their factories. More joined the next day. Soon, the number of strikers grew to between 20,000 and 30,000. This is why the strike became known as the Uprising of the 20,000.

Most of the strikers were young women, aged 16 to 25. About 75-80% were Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. Another 6-10% were Italian immigrants.

The strikers were protesting against long work hours and low wages. They demanded a 20% pay raise. They also wanted a 52-hour work week, extra pay for overtime, and safer working conditions.

Factory Owners and Supporters

The factory owners, Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, were strongly against unions. They refused the workers' demands. Instead, they hired tough people to attack the strikers. These toughs also paid police officers to arrest strikers for small reasons.

Many wealthy women in New York society supported the strikers. They were sometimes called the "mink brigade" because they wore expensive fur coats. Many of these women belonged to the Colony Club, a fancy club that did not allow Jewish members. This made their support quite surprising.

Members of the "mink brigade" included Anne Tracy Morgan, daughter of the rich banker J. P. Morgan. Another supporter was Alva Belmont, who used to be married to William Kissam Vanderbilt. These wealthy women connected with the strikers through the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL). The WTUL wanted to bring working-class women and middle-class women together.

The WTUL put members of the "mink brigade" on the protest lines with the striking workers. When these upper-class women were arrested, it made front-page news. This did not happen when only working-class women were arrested. Alva Belmont even rented the New York Hippodrome for a large meeting to support the workers. Wealthy women also donated money to help the cause. However, some people and newspapers, like The Call (a socialist newspaper), criticized the wealthy women. They pointed out that some of these women were not always fair to workers themselves.

The strike lasted until February 1910. It ended with an agreement called the "Protocol of Peace." This agreement allowed the strikers to go back to work. Many of the workers' demands were met. They got better pay, shorter hours, and fair treatment for all workers, whether they were in the union or not. However, Blanck and Harris still refused to sign an agreement with the union. They also did not fix major safety problems, like locked doors and unsafe fire escapes.

Legacy of the Strike

The successful strike was a very important moment for the American labor movement. It was especially important for unions in the clothing industry. The strike helped change how industrial workers acted and protested in the United States.

However, the success of the strike was later overshadowed by a terrible event. In March 1911, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire happened. This fire killed many workers, highlighting the dangers that still existed.

The strike also inspired Clara Zetkin to suggest an International Women's Day. This day was first celebrated by the Socialist Party of America in 1909.

See also

In Spanish: Huelga de las camiseras de Nueva York de 1909 para niños

In Spanish: Huelga de las camiseras de Nueva York de 1909 para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |