Optimates and populares facts for kids

Optimates (pronounced op-tih-MAY-tees) and populares (pronounced pop-yoo-LAIR-eez) were two different ways politicians acted in the late Roman Republic. These words, from Latin, mean "best ones" (optimates) and "supporters of the people" (populares). They describe how Roman leaders tried to gain power and influence.

It's important to know that these weren't like modern political parties with clear rules or memberships. Instead, they were more like different styles or strategies politicians used. Optimates generally supported the power of the Senate, which was a council of important Roman leaders. They often worked within the Senate to get things done. On the other hand, populares tried to gain support from the common people by proposing laws in the popular assemblies, which were meetings where Roman citizens could vote. They often did this even if the Senate disagreed.

Roman writers from the 1st century BC, like Cicero, wrote about these terms. Cicero especially explained the difference between optimates and populares in his speech Pro Sestio in 56 BC. For a long time, people thought they were like political parties, but today, most historians agree they were not. Roman politics was more about individual leaders and their families trying to get ahead, rather than strict party lines.

Contents

Understanding Roman Political Styles

Historians today agree that optimate and popularis didn't refer to actual political parties. Unlike today, Roman politicians didn't run for office with a party's plan. They relied on their own reputation and skills. For example, groups who opposed powerful alliances like the First Triumvirate didn't always work together. They often formed temporary groups based on what was being debated or who they knew. This meant there were no clear "optimate" or "popularis" groups like we have conservative or liberal parties today.

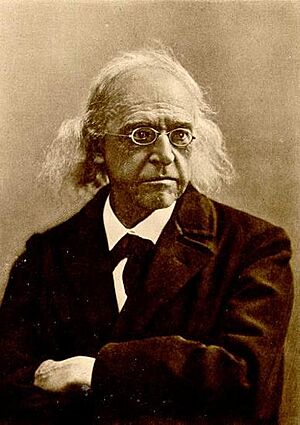

Many experts, like Erich S. Gruen, believe these labels can actually make Roman politics harder to understand. He argued that optimates was often just a way to praise a powerful leader, not a political label. Modern discussions now focus on whether these terms showed a real difference in ideas among Roman leaders, or if they were just words used in debates.

The Optimates Approach

Traditionally, optimates were seen as leaders who protected their own wealth and power. They were thought to be like modern conservatives, against sharing wealth and wanting less government control. They usually focused on strengthening the Senate's power over other parts of the government, like the popular assemblies. Sometimes, optimates are simply defined as those who were against the populares.

However, this idea of a "senatorial party" or "fiscal conservatives" doesn't quite fit when you look closely at the facts. Almost all active politicians were senators, so calling them a "senatorial party" doesn't really explain much. Also, policies like land redistribution or grain subsidies weren't only supported by populares. The Senate itself had managed large land settlements in the past, and rich Romans sometimes gave out grain privately.

In fact, some politicians who were usually called optimate supported policies that seemed popularis, and vice versa:

- Marcus Livius Drusus, who was supported by the Senate, brought in land reform laws. This made his policies sound popularis, even though he had Senate support.

- Cato the Younger, known as a strong optimate, supported giving out more grain during his time as a tribune. This was a popularis idea.

- Sulla, a very conservative leader, probably took and gave out more land in Italy than any other Roman politician. This was a popularis action.

- Julius Caesar, often seen as popularis, actually reduced the number of people getting grain in Rome when he was dictator. This was an optimate-like action.

This shows that leaders didn't always stick to one "side." The term optimate was also used generally to mean the wealthy classes in Rome or the leaders of other countries. If optimates just meant the Senate's elite, then populares (who were also senators) would also be optimates, which makes the terms confusing.

The Populares Approach

Today, when historians talk about populares, they don't mean a planned "party" with a specific set of beliefs. Instead, it refers to a type of senator who, at a certain moment, acted as a "man of the people." This is different from the 19th-century idea that populares were a group of aristocrats who truly believed in democracy and supported the common people.

A very important idea from historian Christian Meier describes a popularis as a senator who used the popular assemblies to pass laws, even if the Senate disagreed. This was often a way for politicians to get ahead in Roman politics. In this view, a popularis politician was someone who:

- Used the common people, rather than the Senate, to achieve their goals.

- Often did this to gain personal advantage.

Ratio popularis (The People's Way)

The ratio popularis was a strategy where politicians brought political issues directly to the people for a vote. They did this when they couldn't get what they wanted through the usual process in the Senate. The Roman government was set up with both the Senate and the people having power. So, if a senator disagreed with his fellow senators, he could turn to the people for support. This approach often involved a style of speaking that appealed to the public, focusing less on specific policies and even less on a fixed set of beliefs.

Laws proposed by popularis politicians often had to directly benefit voters in the assemblies. This was because they needed strong public support to overrule the Senate. These benefits included things like debt relief, land redistribution, and grain handouts. For example, early popularis tactics by Tiberius Gracchus focused on the needs of rural voters who had moved to Rome. Later, Clodius's tactics focused on the interests of the urban poor.

Popularis causes weren't just about money or goods. They also argued about the proper role of the Assemblies in the Roman state, suggesting that the people should have the ultimate power. Other benefits they proposed aimed to empower their supporters in the assemblies. These included introducing secret ballots, giving back rights to tribunes after Sulla's dictatorship, allowing non-senators on juries, and letting people elect priests. All these actions helped a wide range of non-senatorial supporters, from wealthy businessmen (called equites) to the poor city dwellers.

Ideas Behind the Actions

One big question today is whether politicians who used the ratio popularis actually believed in the ideas they promoted. It's hard to know for sure, as we don't have their private thoughts.

Some historians believe that popularis politicians had an underlying belief in popular sovereignty, meaning the people should rule. They might have criticized the Senate's authority and argued that the popular assemblies should control the republic. They often used the word libertas (liberty or freedom) to talk about the people's power to make laws. Some scholars, like T. P. Wiseman, argue these differences showed "rival ideologies" about what the Roman Republic should be.

However, this idea doesn't mean there were political parties. It focuses more on motivations and policies. There's no agreement among historians on whether Roman politicians were truly divided this way. Also, this idea doesn't fully explain why some politicians, like Publius Sulpicius Rufus, were called popularis even when their policies didn't seem to help the average Roman voter much. All politicians claimed to be acting in the public interest, so simply saying someone benefited the people isn't enough to define them.

How They Talked About It

The way the Roman government was set up naturally turned disagreements into arguments between the "people" and the "aristocracy." If tribunes couldn't get the Senate's support, they would go to the people. To justify this, they would use common arguments about the people's power. Their opponents would then use arguments about the Senate's authority. Young Roman politicians often used bold speeches or controversial ideas to get noticed during their short one-year terms.

Popularis speeches often used ideas that Romans valued, like libertas (liberty), leges (laws), and mos maiorum (ancestral customs). They also criticized the Senate for not governing well. When politicians debated laws in public, they didn't talk about party lines. They focused on whether the proposed law truly helped the people, or if the person proposing it was just seeking personal gain. This led to debates about a politician's trustworthiness.

Both optimates and populares agreed on core Roman values, like liberty and the idea that the Roman people were ultimately sovereign. Much of the difference between them came from how they spoke, not necessarily from different policies. Even if they strongly argued for the people's interests, the Roman Republic never saw real attempts to change Roman society or shift the balance of power.

How Ancient Romans Used the Terms

Beyond how modern historians use these terms, the words popularis and optimates also appear in ancient Roman writings.

In Latin, the word popularis usually meant "fellow citizen" or "compatriot." It could also be used negatively to describe politicians who just tried to please the crowd, or actions done in front of large groups of people. The word optimates was used less often, but it referred to aristocrats or the ruling class in general.

Cicero's View

In his private letters, Cicero often used popularis to mean "popularity." In his philosophical writings, it could mean "the majority of the people" or describe a good style for public speaking.

The idea that populares and optimates were opposing groups mostly comes from Cicero's speech Pro Sestio. He gave this speech to defend a friend who helped him return from exile, after being banished by his political enemy Clodius. Cicero's description that populares "aim to please the multitude" is seen as a strong argument he made to win his case. His claims that popularis tactics came from not getting Senate support or from personal grudges are also questionable.

Cicero's speech painted optimates as "honorable, honest, and upright" people who protected the state and its citizens' freedom. He presented populares as less honorable, trying to stir up the crowds. Cicero's description of Clodius as popularis focused on him being a demagogue (someone who gains power by appealing to people's emotions), rather than attacking the rights of the people.

However, Cicero didn't always use the word this way. During his time as consul (a top Roman official), he claimed to be popularis because he had been elected by the people. He also used popularis to describe himself in other speeches, and even to describe actions by others, like Nasica and Opimius, who killed Tiberius Gracchus and Gaius Gracchus. In these cases, popularis meant someone "truly acting in the interest of the people," not someone opposed to optimates.

Sallust's View

Sallust, a Roman politician and historian who lived during Julius Caesar's time, didn't use the word optimas (or optimates) at all in his writings. He used popularis only a few times, and it always referred to countrymen or comrades, not political groups. Historians think he might have avoided the word because it was too unclear.

In his book about the Jugurthine War, Sallust did talk about two groups: the people (populus) and the nobles (nobilitas). He described a small, corrupt part of the Senate as an oligarchy (rule by a few) against the rest of society. But these "nobles" were defined by their family history, not by their political ideas. Sallust didn't give labels to the dissenting nobles because they didn't have common traits. He thought Roman politicians often used terms like "liberty of the Roman people" or "authority of the Senate" just to get ahead.

How Historians Have Studied These Terms

The traditional idea of optimates and populares as political parties came from the 19th-century historian Theodor Mommsen. He thought they were like modern parliamentary parties, with an aristocratic party and a democratic party. For example, some scholars from that time believed the optimates were the ones who killed Tiberius Gracchus in 133 BC. Mommsen also suggested these labels became common around the time of the Gracchi brothers.

However, this view started to change around 1910. Historians like Gelzer argued that Roman politicians didn't rely on organized parties. Instead, they built support through personal relationships. Later, Gelzer still saw an ideological side to popularis, but he thought popularis politicians were more interested in getting the people's support for their plans than truly carrying out the people's will.

By the 1930s, a less ideological view became popular. It suggested that Roman politics was controlled by powerful aristocratic families, not by groups with shared beliefs. Ronald Syme, in his 1939 book Roman Revolution, wrote that Roman political life was shaped by the struggle for power, wealth, and fame among the nobles themselves, not by parties or programs. He saw it as conflicts between individuals or family groups, sometimes open, sometimes secret.

Christian Meier, in 1965, pointed out that "popular" politics was hard to understand because the people themselves didn't start political actions. They were "directed" by the leaders they elected. He also noted that very few populares seemed to have long-term goals; most acted in a popularis way for only a short time.

Meier suggested four meanings for popularis:

- Politicians who acted as champions of the people against the Senate.

- Politicians who manipulated the popular assemblies.

- Politicians who took up a "people's cause" and showed off the people's support.

- A method used by politicians to prolong their careers using "popular" means.

His analysis saw popularis as a method used by those who opposed the Senate's majority. Erich Gruen, in his famous 1974 book Last Generation of the Roman Republic, completely rejected the terms. He said optimates didn't identify a political group and was just a way to show approval. He felt that applying terms like "senatorial party" or "popular party" to Roman politics made things confusing.

In the 1980s and 90s, historian P. A. Brunt argued against the idea of political parties but leaned towards an ideological difference. He said that changing alliances among senators meant there couldn't be lasting political groups like optimates or populares. He believed the difference wasn't about permanent groups, but about supporting or opposing the Senate. Popularis politicians would turn to the popular assemblies if they thought the people's involvement was needed, based on their idea of what was best for the public.

More recently, in 2010, M. A. Robb argued that the labels populares and optimates came mostly from Cicero's writings and didn't match real parties or policies. She noted that Romans themselves didn't commonly use these terms to describe politicians. For example, Julius Caesar never called himself a member of a populares "faction." Robb suggests that instead of populares for demagoguery, Romans would have used seditiosi (meaning rebellious or disruptive). Similarly, Henrik Mouritsen, in his 2017 book Politics in the Roman Republic, completely rejects these categories, supporting the idea of "politics without 'parties'," where politicians sometimes acted without the full support of their peers.

There's still an ongoing debate among historians about how useful these terms are. Some, like Andrew Lintott, argue that despite coming from the same social class, there was a real difference in ideas, as highlighted by Cicero. Others, like T. P. Wiseman, believe the terms are useful for describing different political ideas, rather than political groups.