Phonological history of Old English facts for kids

The Old English language changed a lot over time. Its sounds, or phonological system, went through many shifts. For example, some vowel shifts happened, and certain sounds like 'k' and 'g' became softer, a process called palatalisation. This happened in many words.

If you want to know about how the language developed before Old English, you can look up Proto-Germanic language.

Contents

- Understanding Old English Sounds

- How Old English Sounds Changed

- Nasal Sounds Disappearing

- First 'a' Sound Change

- Diphthongs Becoming Single Vowels

- Second 'a' Sound Change

- Diphthongs Changing Their Shape

- Breaking and Retraction of Vowels

- 'a'-Restoration

- Palatalization: Softening Sounds

- Second Fronting

- Palatal Diphthongization (Again)

- 'r' Sound Switching Places

- I-mutation (or i-umlaut)

- Vowels Disappearing in the Middle of Words

- High Vowels Disappearing

- Losing 'j' Sounds

- Back Mutation (Again)

- Anglian Smoothing

- 'h' Sound Disappearing

- Vowels Merging Together

- Palatal Umlaut (Another Umlaut)

- Unstressed Vowels Changing

- Diphthong Changes Over Time

- Old English Dialects

- Summary of Vowel Changes

- How Old English Led to Modern English

Understanding Old English Sounds

When we talk about how Old English words sounded, we use special ways to write them down. This helps us understand their pronunciation.

- Words written in italics are either Old English words as they were spelled, or they are reconstructed forms (how we think they might have sounded). Sometimes, Old English spelling can be tricky. So, extra marks are added to show the exact sound, like ċ, ġ, ā.

- Sounds written between /slashes/ or [brackets] show how words were pronounced. We use the IPA for this. It is a special alphabet for sounds.

Old English had many different vowel sounds, both short and long. It also had sounds like 'c' and 'g' that could be pronounced in different ways, sometimes hard (like in 'cat') and sometimes soft (like in 'church' or 'gem').

How Old English Sounds Changed

Many sound changes happened in Old English even before people started writing it down. These changes mostly affected vowels. This is why Old English words often look very different from similar words in languages like Old High German. Old High German is much closer to their shared ancestor, West Germanic. These changes happened in a certain order, which helps us understand them.

Nasal Sounds Disappearing

Sometimes, a nasal sound (like 'n' or 'm') would disappear before certain other sounds. When this happened, the vowel before it would change. This is why words like modern English five and mouth are different from German fünf and Mund. This change is called the Ingvaeonic nasal spirant law.

First 'a' Sound Change

The Anglo-Frisian languages (which include Old English) had a special sound change. A long 'a' sound (like in 'father') changed to an 'ae' sound (like in 'cat', but longer). This happened unless it was followed by 'n' or 'm', or if the vowel itself was nasal.

Later, in some dialects, this 'ae' sound changed even further to a long 'e' sound (like in 'sleep'). For example, West Saxon Old English had slǣpan (to sleep) and sċēap (sheep). But in the Anglian dialect, these became slēpan and sċēp. Modern English words like sleep and sheep come from the Anglian way of saying them.

Diphthongs Becoming Single Vowels

A diphthong is a vowel sound that combines two vowel sounds, like 'oy' in 'boy'. In Old English, some diphthongs became single vowel sounds. This happened after the first 'a' sound change. For example, the Proto-Germanic word *stainaz became Old English stān (modern stone). This is different from the word in Gothic, which is stáin.

Second 'a' Sound Change

This change is similar to the first 'a' sound change, but it affected short 'a' sounds instead of long ones. The short 'a' (like in 'cat') changed to 'æ' (like in 'trap'). Again, this did not happen if 'n' or 'm' followed the vowel.

This change was important for words like ġefen (given). However, the word ġefan (to give) kept its original 'a' sound because of a later change called 'a'-restoration.

Diphthongs Changing Their Shape

Old English had diphthongs where both parts of the vowel sound were at the same height in your mouth. This is called diphthong height harmonisation.

- The 'au' sound became 'æu' and then changed to 'æa', spelled ea.

- The 'eu' sound became 'eo', spelled eo.

- The 'iu' sound became 'iu', spelled io.

Other diphthongs also appeared later due to processes like breaking and palatal diphthongisation. These could be short or long.

Breaking and Retraction of Vowels

Breaking is when short front vowels (like 'i', 'e', 'æ') changed into diphthongs (like 'iu', 'eo', 'æa'). This happened when they were followed by certain sounds, like 'h', 'w', or 'r' or 'l' plus another consonant. Long vowels could also break, but only before 'h'.

For example:

- weorpan (to throw) came from an earlier *werpan.

- feoh (money) came from *feh.

Sometimes, instead of breaking, the 'æ' sound changed back to 'a'. This is called retraction. This happened in the Anglian dialect, which is part of where Modern English comes from. This is why Old English ceald (cold) became modern English "cold" instead of "*cheald".

Both breaking and retraction are ways that vowels changed to sound more like the consonant that came after them.

'a'-Restoration

After breaking, the short 'æ' sound (and sometimes long 'æ') changed back to 'a' if there was a back vowel (like 'u' or 'o') in the next syllable. This is called a-restoration because it brought back some of the original 'a' sounds that had changed earlier.

This change caused some words to have different vowel sounds depending on their form. For example, in Old English, dæġ (day) had 'æ', but its plural dagas (days) had 'a'.

Palatalization: Softening Sounds

Palatalization is a big change where the hard 'k' and 'g' sounds became softer. This usually happened when they were followed by front vowels (like 'i' or 'e').

- 'k' became 'ch' (like in church). So, Old English ċīdan (to chide) came from an earlier word with a 'k' sound.

- 'sk' became 'sh' (like in ship). So, Old English fisċ (fish) came from an earlier word with 'sk'.

- Hard 'g' became 'j' (like in bridge). So, Old English bryċġ (bridge) came from an earlier word with a hard 'g'.

- Soft 'g' became 'y' (like in yes). So, Old English ġeaf (gave) came from an earlier word with a soft 'g'.

This change is similar to how sounds changed in Italian and Swedish.

Sometimes, these soft sounds changed back to hard sounds if they were followed by a consonant. For example, sēċan (to seek) had a soft 'ch' sound, but sēcþ (he seeks) had a hard 'k' sound.

Old English spelling didn't always show these changes clearly. Modern versions of Old English texts often add a dot (like ⟨ċ⟩ or ⟨ġ⟩) to show when a sound was soft.

Words borrowed from Old Norse (the language of the Vikings) often didn't go through palatalization. This is why we have pairs of words like shirt (from Old English, with palatalization) and skirt (from Old Norse, without palatalization). Both words come from the same root!

Second Fronting

Second fronting was another change where 'a' became 'æ', and 'æ' became 'e'. This happened later than the other 'a' sound changes. It only happened in a specific part of England, in the Mercian dialect, not in the standard West Saxon dialect.

Palatal Diphthongization (Again)

Front vowels like 'e', 'ē', 'æ', and 'ǣ' often became diphthongs (like 'ie', 'īe', 'ea', 'ēa') after the soft 'ch', 'j', and 'sh' sounds.

- sċieran (to cut) came from a word with 'e'.

- ġiefan (to give) came from a word with 'e'.

Interestingly, back vowels like 'u', 'o', and 'a' were also sometimes spelled as 'eo' and 'ea' after these soft sounds. However, it's likely that their pronunciation didn't actually change. For example, ġeong (young) was probably still pronounced with a 'u' sound, not 'eo'. This is because in Modern English, it's still "young," not "*yeng."

'r' Sound Switching Places

Sometimes, the 'r' sound and a short vowel would switch places. This is called metathesis. It usually happened when 's' or 'n' came next.

- berstan (to burst) is an example. In Icelandic, it's bresta.

- gærs (grass) is another. In Gothic, it's gras.

Not all words that could have changed this way actually did. Many words in Modern English still have the original order of sounds.

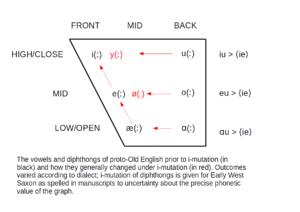

I-mutation (or i-umlaut)

I-mutation was a very important sound change in Old English. It made vowels in a word change their sound (become more front or higher) if an 'i' or 'y' sound was in the next syllable. Often, the 'i' or 'y' sound that caused the change later disappeared.

This is why we have words like men (from man), feet (from foot), and mice (from mouse). The vowel in the plural form changed because of an 'i' sound that used to be in the ending. Other examples include elder (from old), fill (from full), and length (from long).

Vowels Disappearing in the Middle of Words

In the middle of words, short 'a', 'æ', and 'e' vowels often disappeared if they were in an open syllable (a syllable ending in a vowel). This is called medial syncopation.

This happened after i-mutation. For example, the word mæġden (maiden) changed like this:

- Original form: *magadīną

- After some changes: *mægædīn

- After palatalization: *mæġædīn

- After i-mutation: *mæġedīn

- After medial syncopation: *mæġdīn

- Finally: mæġden

High Vowels Disappearing

Short 'i' and 'u' vowels in unstressed syllables often disappeared, especially if the syllable before them was long. This is called high vowel loss.

This change affected how many words ended. For example, ġiefu (gift) kept its 'u' ending because the first syllable was short. But lār (teaching) lost its ending because its first syllable was long.

Losing 'j' Sounds

The 'j' sound (and its variant 'ij') in the middle of words was lost, but only after a long syllable. This happened after high vowel loss.

- dēman (to judge) came from *dø̄mijan.

- settan (to set) came from *settjan.

This change also happened in other West Germanic languages, but sometimes a bit differently.

Back Mutation (Again)

Back mutation is when short 'e', 'i', and sometimes 'a' changed into diphthongs (like 'eo', 'io', 'ea'). This happened when a back vowel (like 'u', 'o', 'a') was in the next syllable. This is similar to breaking.

- seofon (seven) came from *sebun.

- eofor (boar) came from *eburaz.

- ealu (ale) came from *aluþ.

There were rules about when back mutation happened. For example, in the standard West Saxon dialect, it usually only happened before 'f', 'b', 'w', 'l', or 'r'.

Anglian Smoothing

In the Anglian dialects (from central and northern England), a process called smoothing undid some of the breaking changes. Diphthongs often became single vowels again, especially before 'h', 'g', 'k', or 'r' or 'l' followed by one of these sounds.

- ea became æ or e.

- ēa became ē.

- eo became e.

- ēo became ē.

This is why there are differences between standard Old English (West Saxon) and Modern English spelling. For example, Old English ēage (eye) became ēge in Anglian.

'h' Sound Disappearing

The 'h' sound often disappeared between vowels or between a voiced consonant and a vowel. When a short vowel was before the 'h', it became longer to make up for the lost 'h'. This is called compensatory lengthening.

- sċōs (shoe, plural) came from *sċohes.

- fēos (money, plural) came from *feohes.

Vowels Merging Together

When two vowels were next to each other without a consonant in between, they often merged into a single long vowel. This is called vowel assimilation. This happened a lot after the 'h' sound disappeared.

- frēond (friend) came from *frijōndz.

- sǣm (sea, plural) came from *sǣwum.

Palatal Umlaut (Another Umlaut)

Palatal umlaut is when short 'e', 'eo', 'io' became 'i' (or sometimes 'ie') before 'ht', 'hs', or 'hþ' at the end of a word.

- riht (right) is an example.

- cniht (boy, modern knight) is another.

Unstressed Vowels Changing

Vowels in unstressed syllables (syllables that aren't emphasized) changed a lot. They often became shorter or disappeared completely.

- Long vowels became short.

- Many short vowels disappeared.

- The remaining vowels in unstressed syllables mostly became 'u', 'a', or 'e'.

Diphthong Changes Over Time

In early West Saxon Old English, the diphthongs io and īo merged with eo and ēo. Also, the diphthongs ie and īe became an "unstable 'i'" sound, which later merged into a 'y' sound in late West Saxon.

All the remaining Old English diphthongs eventually became single vowel sounds in the early Middle English period.

Old English Dialects

Old English had four main dialects: West Saxon, Mercian, Northumbrian, and Kentish.

- West Saxon and Kentish were spoken in the south, below the River Thames.

- Mercian was in the middle of the country.

- Northumbrian was in the north, from the Humber River up to Scotland.

Mercian and Northumbrian are often grouped together as "Anglian" dialects.

The biggest differences were between West Saxon and the other dialects, especially in the front vowels and diphthongs. Northumbrian was special because it had much less palatalisation. This is why some Modern English words have a hard 'k' or 'g' sound where you might expect a soft one from Old English. This could be because of Northumbrian influence or direct borrowing from Scandinavian languages.

The early Kentish dialect was similar to Anglian. But around the 9th century, all its front vowels ('æ', 'e', 'y', long and short) merged into 'e'.

Modern English mostly comes from the Anglian dialect, not the standard West Saxon dialect. However, because London is located where the Anglian, West Saxon, and Kentish dialects met, some words from West Saxon and Kentish also made their way into Modern English. For example, the word "bury" has its spelling from West Saxon but its pronunciation from Kentish.

The Northumbrian dialect is the ancestor of the Scots language spoken in Scotland. The lack of palatalization in Northumbrian is still seen in pairs of words like Scots kirk (church) and brig (bridge).

Summary of Vowel Changes

This table shows how some West Germanic vowels changed into Old English vowels, and how they were affected by i-umlaut. This is mainly about stressed syllables. Unstressed vowels changed much more, often becoming shorter or disappearing.

| West Germanic | Condition | Process | Old English | i-umlaut | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *a | Anglo-Frisian brightening | æ | e | *dagaz > dæġ "day"; *fastaz > fæst "fast (firm)"; *batizǫ̂ > betera "better"; *taljaną > tellan "to tell" | |

| +n,m | a,o | e | *namǫ̂ > nama "name"; *langaz > lang, long "long"; *mannz, manniz > man, mon "man", plur. men "men" | ||

| +mf,nþ,ns | Ingvaeonic nasal spirant law | ō | ē | *samftijaz, samftô > sēfte, *sōfta >! sōfte "soft"; *tanþs, tanþiz > tōþ, plur. tēþ "tooth"; *gans, gansiz > gōs "goose", plur. gēs "geese" | |

| (West Saxon) +h,rC,lC | breaking | ea | ie | *aldaz, aldizǫ̂ > eald "old", ieldra "older" (cf. "elder"); *armaz > earm "arm"; Lat. arca > earc "arc"; *darniją > dierne "secret"; *ahtau > eahta "eight" | |

| (Anglian) +h | breaking, Anglian smoothing | æ | e | *ahtau > æhta "eight" | |

| (Anglian) +lC | retraction | a | æ | *aldaz, aldizǫ̂ > ald "old", ældra "older" (cf. "elder") | |

| (Anglian) +rc,rg,rh | breaking, Anglian smoothing | e | e | Lat. arca > erc "arc" | |

| (Anglian) +rC (C not c,g,h) | breaking | ea | e | *armaz > earm "arm"; *darniją > derne "secret" | |

| (West Saxon) +hV,hr,hl | breaking, h-loss | ēa | īe | *slahaną > slēan "to slay"; *stahliją > stīele "steel" | |

| (Anglian) +hV,hr,hl | breaking, Anglian smoothing, h-loss | ēa | ē | *slahaną, -iþi > slēan "to slay, 3rd sing. pres. indic. slēþ "slays"; *stahliją > stēle "steel" | |

| (West Saxon) k,g,j+ | palatal diphthongization | ea | ie | Lat. castra > ċeaster "town, fortress" (cf. names in "-caster, -chester"); *gastiz > ġiest "guest" | |

| before a,o,u | a-restoration | a | (by analogy) æ | plur. *dagôs > dagas "days"; *talō > talu "tale"; *bakaną, -iþi > bacan "to bake", 3rd sing. pres. indic. bæcþ "bakes" | |

| (mostly non-West-Saxon) before later a,o,u | back mutation | ea | eo | *alu > ealu "ale"; *awī > eowu "ewe", *asiluz > non-West-Saxon eosol "donkey" | |

| before hs,ht,hþ + final -iz | palatal umlaut | N/A | i (occ. ie) | *nahtiz > nieht > niht "night" | |

| *e | e | N/A | *etaną > etan "to eat" | ||

| +m | i | N/A | *nemaną > niman "to take" | ||

| (West Saxon) +h,rC,lc,lh,wV | breaking | eo | N/A | *fehtaną > feohtan "to fight"; *berkaną > beorcan "to bark"; *werþaną > weorðan "to become" | |

| (Anglian) +h,rc,rg,rh | breaking, Anglian smoothing | e | N/A | *fehtaną > fehtan "to fight"; *berkaną > bercan "to bark" | |

| (Anglian) +rC (C not c,g,h); lc,lh,wV | breaking | eo | N/A | *werþaną > weorðan "to become" | |

| +hV,hr,hl | breaking, (Anglian smoothing,) h-loss | ēo | N/A | *sehwaną > sēon "to see" | |

| + late final hs,ht,hþ | palatal umlaut | i (occ. ie) | N/A | *sehs > siex "six"; *rehtaz > riht "right" | |

| (West Saxon) k,g,j+ | palatal diphthongization | ie | N/A | *skeraną > sċieran "shear" | |

| *i | i | i | *fiską > fisċ "fish"; *itiþi > 3rd sing. pres. indic. iteþ "eats"; *nimiþi > 3rd sing. pres. indic. nimeþ "takes"; *skiriþi > 3rd sing. pres. indic. sċirþ "shears" | ||

| + mf,nþ,ns | Ingvaeonic nasal spirant law | ī | ī | *fimf > fīf "five" | |

| (West Saxon) +h,rC | breaking | io > eo | ie | *Pihtôs > Piohtas, Peohtas "Picts"; *lirnōjaną > liornian, leornian "to learn"; *hirdijaz > hierde "shepherd"; *wirþiþi > 3rd sing. pres. indic. wierþ "becomes" | |

| (Anglian) +h,rc,rg,rh | breaking, Anglian smoothing | i | i | *stihtōjaną > stihtian "to establish" | |

| (Anglian) +rC (C not c,g,h) | breaking | io > eo | i | *a + firrijaną > afirran "to remove" (cf. feorr "far") | |

| (West Saxon) +hV,hr,hl | breaking, h-loss | īo > ēo | īe | *twihōjaną > twīoġan, twēon "to doubt" | |

| (Anglian) +hV,hr,hl | breaking, Anglian smoothing, h-loss | īo > ēo | ī | *twihōjaną > twīoġan, twēon "to doubt"; *sihwiþi > 3rd sing. pres. indic. sīþ "sees" | |

| before w | breaking | io > eo | i | *niwulaz > *niowul, neowul "prostrate"; *spiwiz > *spiwe "vomiting" | |

| before a,o,u | back mutation | i (io, eo) | N/A | *miluks > mioluc,meolc "milk" | |

| *u | u | y | *sunuz > sunu "son"; *kumaną, -iþi > cuman "to come", 3rd sing. pres. indic. cymþ "comes"; *guldijaną > gyldan "to gild" | ||

| + mf,nþ,ns | Ingvaeonic nasal spirant law | ū | ȳ | *munþs > mūþ "mouth"; *wunskijaną > wȳsċan "wish" | |

| before non-nasal + a,e,o | a-mutation | o | (by analogy) e | *hurną > horn "horn"; *brukanaz > brocen "broken"; *duhter, duhtriz > dohter "daughter", plur. dehter "daughters" | |

| +hV,hr,hl | h-loss | ū | ȳ | *uhumistaz > ȳmest "highest" | |

| (*ē >) *ā | Anglo-Frisian brightening | (West Saxon) ǣ | ǣ | *slāpaną > slǣpan "to sleep", Lat. strāta > strǣt "street"; *dādiz > dǣd "deed" | |

| (Anglian) ē | ē | *slāpaną > slēpan "to sleep", Lat. strāta > strēt "street"; *dādiz > dēd "deed"; Lat. cāseus > ċēse "cheese"; *nāhaz, nāhistaz > nēh "near" (cf. "nigh"), superl. nēhst "nearest" (cf. "next") | |||

| (West Saxon) k,g,j+ | palatal diphthongization | ēa | īe | *jārō > ġēar "year"; Lat. cāseus > ċīese "cheese" | |

| +n,m | ō | ē | *mānǫ̂ > mōna "moon"; *kwāniz > kwēn "queen" | ||

| (West Saxon) +h | breaking | ēa | īe | *nāhaz, nāhistaz > nēah "near" (cf. "nigh"), superl. nīehst "nearest" (cf. "next") | |

| +w;ga,go,gu;la,lo,lu | a-restoration | ā | ǣ | *knāwaną, -iþi > cnāwan "to know", 3rd sing. pres. indic. cnǣwþ "knows" | |

| *ē₂ | ē | ē | *mē₂dą > mēd "reward" | ||

| *ō | ō | ē | *fōts, fōtiz > fōt "foot", plur. fēt "feet" | ||

| *ī | ī | ī | *wībą > wīf "wife"; *līhiþi > Anglian 3rd sing. pres. indic. līþ "lends" | ||

| (West Saxon) +h | breaking | īo > ēo | īe | *līhaną, -iþi > lēon "to lend", 3rd sing. pres. indic. līehþ "lends" | |

| *ū | ū | ȳ | *mūs, mūsiz > mūs "mouse", plur. mȳs "mice" | ||

| *ai | ā | ǣ | *stainaz > stān "stone", *kaisaraz > cāsere "emperor", *hwaitiją > hwǣte "wheat" | ||

| *au | ēa | (West Saxon) īe | *auzǭ > ēare "ear"; *hauzijaną > hīeran "to hear"; *hauh, hauhist > hēah "high", superl. hīehst "highest" | ||

| (Anglian) ē | *auzǭ > ēare "ear"; *hauzijaną > hēran "to hear" | ||||

| (Anglian) +c,g,h;rc,rg,rh;lc,lg,lh | Anglian smoothing | ē | ē | *hauh, hauhist > hēh "high", superl. hēhst "highest" | |

| *eu | ēo | N/A | *deupaz > dēop "deep"; *fleugǭ > flēoge "fly"; *beudaną > bēodan "to command" | ||

| (Anglian) +c,g,h;rc,rg,rh;lc,lg,lh | Anglian smoothing | ē | N/A | *fleugǭ > flēge "fly" | |

| *iu | N/A | (West Saxon) īe | *biudiþi > 3rd sing. pres. indic. bīett "commands"; *liuhtijaną > līehtan "to lighten" | ||

| (Anglian) īo | *biudiþi > 3rd sing. pres. indic. bīott "commands" | ||||

| (Anglian) +c,g,h;rc,rg,rh;lc,lg,lh | Anglian smoothing | N/A | ī | *liuhtijaną > līhtan "to lighten" |

How Old English Led to Modern English

The way we speak English today comes from the changes that happened between Old English and Middle English. Modern English spelling often shows how words were pronounced in Middle English.

Many vowels changed in complex ways, especially before the 'r' sound. New diphthongs also appeared in Middle English.

Modern English comes mostly from the Middle English spoken in London. This was a mix of Anglian Old English, with some West Saxon and Kentish influences.

One big difference between the dialects was how the Old English 'y' sound was handled.

- In Kent, 'y' became 'e'.

- In Anglian, 'y' became 'i'.

- In West Saxon, 'y' stayed as 'y' for a long time.

When words with this 'y' sound were borrowed into London Middle English, the 'y' was often changed to 'u'.

- Words like "gild," "did," "sin," "mind," "dizzy," and "lift" show the normal Anglian development.

- "Much" comes from the West Saxon development.

- "Merry" comes from the Kentish development.

- "Build" and "busy" have West Saxon spelling but Anglian pronunciation.

- "Bury" has West Saxon spelling but Kentish pronunciation.