Black petrel facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Black petrel |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Procellariiformes |

| Family: | Procellariidae |

| Genus: | Procellaria |

| Species: |

P. parkinsoni

|

| Binomial name | |

| Procellaria parkinsoni Gray, 1862

|

|

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The black petrel (Procellaria parkinsoni), also called Parkinson's petrel, is a medium-sized petrel with black feathers. It is the smallest bird in the Procellaria family. These birds are special because they only breed in New Zealand, specifically on Great Barrier Island and Little Barrier Island. When they are not breeding, they fly far across the ocean, sometimes reaching Australia and Ecuador.

Contents

Understanding the Black Petrel

What is a Black Petrel?

The black petrel was officially named in 1862 by George Robert Gray, an English zoologist. He gave it the scientific name Procellaria parkinsoni. The name 'Procellaria' comes from a Latin word meaning "storm," because petrels are often seen during stormy weather. The second part, 'parkinsoni,' honors Sydney Parkinson, an artist and collector. This species is considered 'monotypic,' meaning there are no different types or subspecies of black petrels.

How to Identify a Black Petrel?

The black petrel has completely black feathers. Its legs and beak are also black, but its beak has some lighter parts. It is a medium-sized petrel. Males usually weigh about 720 grams, and females about 680 grams. They are about 46 centimeters long and have a wingspan of about 115 centimeters.

Where Do Black Petrels Live?

Black petrels are native to New Zealand. They used to live all over the North Island and parts of the South Island. Sadly, predators like wild cats and pigs caused them to disappear from the mainland by the 1950s.

Today, they are mostly seen in the outer Hauraki Gulf from October to May. They now only breed on Great Barrier Island, where about 5,000 birds gather in summer. A smaller group of about 250 birds lives on Little Barrier Island.

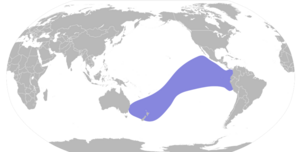

Besides the breeding birds, there are likely another 6,000 young or non-breeding birds at sea. Black petrels can travel from the east coast of Australia all the way to South America, near Mexico, Peru, and the Galapagos islands. It is interesting that male and female birds often look for food in different places.

Black Petrel Behaviour

How Do Black Petrels Breed?

Black petrels breed from October to June in the Hauraki Gulf. Adult birds return to their nesting colonies in mid-October. They clean their burrows and find their mates. Most pairs stay together, but about 12% of them "divorce" each year. Males will return to the same burrow every year.

After mating, the pairs go on a "honeymoon" trip. They return to the colony in late November, and the females lay a single egg. Both parents take turns sitting on the egg for about 57 days (around 8 weeks). The chicks hatch from late January through February.

Chicks stay in the nest for about 107 days (15 weeks). They leave the nest from mid-April to late June. About 75% of chicks survive to leave the nest.

Where Do Young Black Petrels Go?

Adults and chicks fly to South America for the winter, usually to the coast of Ecuador. Only about 10% of young birds survive their first year. Young birds stay at sea in the West Pacific for 3 to 4 years until they are ready to breed. Their survival rate during this time is about 46%. Birds older than 3 years have a much higher survival rate of 90%.

When they are about four years old, young birds fly back to the colony to find a mate. This search might take one or two breeding seasons.

How Do Black Petrels Find Food?

Black petrels can find food both at night and during the day. They are known to follow fishing boats and dive for bait. They can dive up to 20 meters deep to catch food. Black petrels can travel incredible distances to find food. The longest recorded trip for a bird from Great Barrier Island was 39 days.

Protecting the Black Petrel

The black petrel is classified as "Vulnerable" by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). This means their population is decreasing and they are at risk of extinction. Studies since 1995 show that their numbers are dropping by at least 1.4% each year. A young bird has only a 1 in 20 chance of reaching breeding age. To keep the population stable, each breeding pair needs to successfully raise 20 chicks.

Threats at Sea

Black petrels are often accidentally caught by commercial and recreational fishers, both in New Zealand and other countries. The Ministry of Fisheries in New Zealand estimates that between 725 and 1,524 birds might have been killed each year from 2003 to 2009 by commercial fishing.

Petrels can drown if they get caught on longline hooks, either when the lines are put into the water or pulled onto boats. Fishing for snapper and bluenose with bottom longlines poses the biggest risk. This is especially true where fishing areas overlap with where breeding birds look for food.

Even though many birds are likely caught, fishers report very few deaths. Since 1996, only 38 birds have been reported caught and killed by local commercial fishers in New Zealand waters. This is mainly in tuna longline and snapper fisheries. Less than 0.5% of boats in these high-risk fisheries had observers on board to record catches. The number of deaths in fisheries outside New Zealand is unknown. Recreational fishers also report catching birds, especially in the outer Hauraki Gulf.

Threats on Land

On Great Barrier Island, wild pigs dig up burrows and eat eggs and chicks. For example, in 1996, pigs destroyed 8 burrows in one incident. Wild cats can kill adult birds on the ground or at their nests, as well as chicks. The Department of Conservation tries to control cat numbers in some areas, but there has been no specific protection for the black petrel colony itself.

Rats are also present on Great Barrier Island. While they do eat some eggs and chicks, their impact is smaller, usually between 1% and 6.5% of nests each year. The native kiore cannot even break through a black petrel egg.

Because almost all black petrels breed in one main area on Hirakimata on Great Barrier Island, a single big event like a fire, a severe storm, or a large invasion of predators could be very dangerous for the species.

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |