Protectionism in the United States facts for kids

Protectionism in the United States is an economic idea where a country tries to protect its own industries. It does this by adding taxes or limits on goods coming in from other countries. In the U.S., this idea was very popular in the 1800s. Back then, it mostly helped factories in the Northern states. Southern states, which grew a lot of cotton, wanted free trade to sell their crops easily.

Protectionist rules included tariffs (taxes on imports) and quotas (limits on how much could be imported). They also used subsidies (money from the government) to help local businesses. The goal was to make it harder for foreign goods to compete. This encouraged people to buy things made in the U.S.

After the 1930s, the U.S. started to use fewer protectionist measures. After World War II, the country strongly supported free trade. It helped create the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). This group wanted to make trade easier among all capitalist countries. In 1995, GATT became the World Trade Organization (WTO). Its ideas of open markets and low tariffs became very popular around the world.

Contents

- A Look Back: How Protectionism Started

- North vs. South: Different Views on Trade

- From Colonies to a New Nation (Before 1789)

- Early Years of the Nation (1789–1828)

- Political Parties and Tariffs (1829–1859)

- From Civil War to Early 1900s (1860–1912)

- From 1913 to Today

- Leaders Who Supported Protectionism

- How Globalization Affects the U.S.

- What People Think About Trade

A Look Back: How Protectionism Started

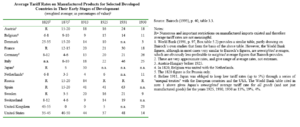

Britain was one of the first countries to protect its new industries. But the U.S. used this idea even more. One historian called the U.S. "the home and stronghold of modern protectionism."

Britain didn't want its American colonies to become industrial. So, it stopped them from making valuable goods. The American Revolution was partly a fight against this rule. After winning independence, the U.S. quickly passed the Tariff Act of 1789. This law put a 5% tax on most imported goods. President George Washington signed it.

Many American thinkers and leaders felt that Britain's free trade ideas weren't right for the U.S. They wanted to protect their own growing industries.

Early Ideas: Alexander Hamilton's Plan

Alexander Hamilton was the first Secretary of the Treasury. He feared that Britain's policies would keep the U.S. as just a producer of farm goods. Washington and Hamilton believed that being truly independent meant being economically independent too. Making more goods at home, especially war supplies, was important for national safety.

Hamilton argued that new industries, called "infant industries," needed help to start. They couldn't compete with foreign companies right away. He suggested using import taxes or even banning some imports. He also thought taxes on raw materials should be low. Hamilton believed that even if prices went up at first, they would become cheaper once a local industry became strong.

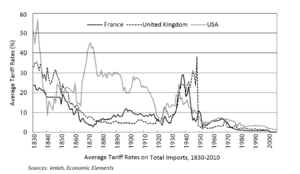

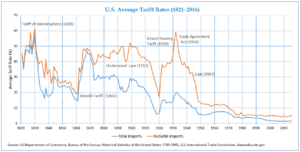

The first tariff law in 1789 set a 5% tax on imports. Between 1792 and 1812, the average tariff was about 12.5%. In 1812, tariffs doubled to 25% to help pay for the war with Britain.

A Big Change in 1816

In 1816, a new law kept tariffs high, especially for cotton, wool, and iron goods. American industries that had grown because of these tariffs wanted them to stay. By 1820, the average U.S. tariff was 40%.

According to historian Michael Lind, protectionism was the main U.S. policy from 1816 until World War II. The U.S. only fully switched to free trade after 1945.

There was a short time of lower tariffs from 1846 to 1857. But after some economic problems, tariffs went up again with the Morrill Tariff in 1861.

Leaders like Senator Henry Clay continued Hamilton's ideas. They called it the "American System."

Tariffs and the Civil War

The American Civil War (1861-1865) was mainly about slavery. But tariffs also played a part. Southern states, which were mostly farms, didn't want protectionism. Northern states, with their factories, did.

Abraham Lincoln, a leader of the new Republican Party, strongly opposed free trade. During the Civil War, he put a 44% tariff on imports. This helped pay for railroads and the war. It also protected American industries. Lincoln once said, "Give us a protective tariff, and we shall have the greatest nation on earth."

From 1871 to 1913, the average U.S. tariff was never below 38%. During this time, the U.S. economy grew very fast. It grew twice as fast as free-trade Britain.

The protectionist period was a "golden age" for American industry. The U.S. changed from a farming country to the world's biggest economic power.

North vs. South: Different Views on Trade

Historically, Southern states didn't need many machines because they had enslaved labor. They sold raw cotton to Britain, which supported free trade.

Northern states wanted to build factories. They needed protection to help their new businesses compete with more advanced British ones. Throughout the 1800s, Northern politicians like Henry Clay supported Hamilton's ideas.

Southern Democrats often fought against high tariffs. But the North had more people, so Northern politicians usually won. One Southern state, South Carolina, even threatened to ignore federal tariff laws. This was called the Nullification Crisis.

When the Whig Party broke apart, Abraham Lincoln's Republican Party took its place. Lincoln, who supported Henry Clay's tariff ideas, was against free trade. He put a 44% tariff in place during the Civil War. This helped build the Union Pacific Railroad and pay for the war.

By Lincoln's time, the Northern states had much more economic power than the South. This helped the North win the war. After the North won, Republicans controlled U.S. politics for many years.

President Ulysses S. Grant once said that England used protectionism for centuries to become strong. He thought the U.S. would do the same. He believed that after 200 years, the U.S. would also adopt free trade, once protectionism had done all it could.

From Colonies to a New Nation (Before 1789)

Before 1775, most American colonies had their own tariffs. British goods often had lower taxes. There were also taxes on ships, enslaved people, and alcohol. Britain wanted to control trade, so only British ships could trade with the colonies. Some American merchants smuggled goods to get around these rules.

During the American Revolution (1775-1783), Britain blocked trade. After the war, from 1783 to 1789, each state made its own trade rules. This often caused problems between states. The new U.S. Constitution, which started in 1789, stopped states from taxing each other's goods. It also banned state taxes on exports.

Early Years of the Nation (1789–1828)

The U.S. Constitution gave the federal government the power to collect taxes and control trade with other countries. It also said that trade between states must be tax-free.

The first U.S. Congress and President George Washington quickly passed the Tariff of 1789. This law put taxes on imported goods. It was needed to raise money for the new government. It also aimed to protect new American industries that had grown during the war. These industries were now threatened by cheaper imports, especially from England.

Tariffs were the main source of money for the federal government until the 1860s. Alexander Hamilton, the first Treasury Secretary, suggested these taxes. He wanted to pay off the country's debts from the Revolutionary War. He also wanted to encourage American manufacturing.

Early on, the U.S. had almost no textile industry. Britain tried to keep its lead in textile manufacturing. It banned the export of textile machines and people who knew how to use them. But Samuel Slater, who knew about textile machines, came to the U.S. illegally in 1789. He helped build the first successful textile factory in the U.S. in 1790. The tariff helped protect this new industry.

After the War of 1812, leaders like Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun pushed for higher tariffs. They said that having home industries was important during wartime. New factories in the Northeast also wanted higher tariffs to protect them from more efficient British producers.

As factories grew, manufacturers and workers wanted even higher tariffs. They believed their businesses needed protection from lower wages and more efficient factories in Europe. The Tariff of 1828, called the "Tariff of Abominations," had very high import taxes. This angered Southern states, especially South Carolina. They had few factories and had to pay more for imported goods. They tried to "nullify" the federal tariff. President Andrew Jackson said he would use the army to enforce the law. A compromise eventually lowered the tariffs over ten years.

Political Parties and Tariffs (1829–1859)

Tariffs became a big political issue. The Whig Party and later the Republicans wanted high tariffs to protect Northern industries. Southern Democrats, who had little industry, wanted lower tariffs. Each party changed tariffs when they were in power.

In 1834, the U.S. paid off its national debt. President Andrew Jackson, a Southern Democrat, cut tariff rates by about half. He also removed almost all federal sales taxes.

Henry Clay and the Whig Party wanted high tariffs to help factories grow quickly. They argued that new "infant industries" were less efficient than European ones. Also, American factory workers earned higher wages. These arguments were very popular in industrial areas.

The Walker Tariff

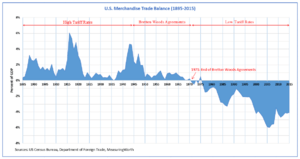

In 1844, James K. Polk became president. He was a Democrat. He passed the Walker Tariff of 1846. This law lowered tariffs by bringing together farmers from all over the country. They wanted tariffs that only raised enough money for the government, without favoring any one part of the country. The Walker Tariff actually increased trade and brought in more money than the higher tariffs.

Low Tariffs in 1857

The Walker Tariff stayed until 1857. Then, tariffs were lowered again to 18%. This happened after Britain removed its own protectionist laws.

Democrats in Congress, mostly from the South, kept lowering tariffs in the 1830s, 40s, and 50s. By 1857, rates were about 15%. This boosted trade so much that government income actually went up. The low rates made Northern factory owners and workers angry. They wanted protection for their growing iron industry. The Republican Party, formed in 1854, also wanted high tariffs. This was part of their plan for the 1860 election.

The Morrill Tariff, which raised tariffs a lot, was passed in March 1861. This was possible because Southern senators left Congress when their states seceded.

Some historians say tariffs were not a main cause of the Civil War. But some documents from Southern states that left the Union did mention tariffs.

From Civil War to Early 1900s (1860–1912)

Civil War Tariffs

During the Civil War, the government needed much more money. So, tariffs were raised again and again. Other taxes, like income taxes, were also added. Most of the money came from loans, not taxes or tariffs.

The Morrill Tariff started a few weeks before the war. It was not collected in the South. The Confederate States of America (CSA) made their own tariff of about 15%. They thought they could pay for their government with tariffs. But the Union Navy blocked their ports. This stopped trade, and the Confederacy got very little money from tariffs.

After the War: Reconstruction

Some historians argued that high tariffs were kept after the Civil War to help Northern factory owners. They said these owners used the Republican Party to keep Southern whites, who wanted low tariffs, out of power.

However, later historians showed that Northern business people had mixed views on tariffs. They were not using Reconstruction policies just to support tariffs.

The Politics of Protection

The iron, steel, and wool industries were strong groups that wanted high tariffs. They usually got them by supporting the Republican Party. Factory workers in the U.S. earned much higher wages than in Europe. They believed this was because of tariffs, so they voted Republican.

Democrats were divided on tariffs. President Grover Cleveland, a Democrat, made low tariffs a main goal in the late 1880s. He argued that high tariffs were unfair taxes on consumers. The South and West generally wanted low tariffs. The industrial East wanted high tariffs. Republican William McKinley was a strong supporter of high tariffs. He promised they would bring wealth to everyone.

After the Civil War, high tariffs stayed because Republicans were in power. They said tariffs brought wealth to the whole country.

U.S. Industry Grows Strong

By the 1880s, American industry and farming were very efficient. They were leaders in the Industrial Revolution. They were not really threatened by cheap imports. No other country could compete with the U.S. in its own large market. In fact, British companies were surprised when cheaper American products started selling in Britain.

Still, some American manufacturers and union workers wanted high tariffs to continue. For example, railroads used a lot of steel. Tariffs made steel more expensive, but this allowed U.S. steel companies to invest a lot of money. They built bigger factories and used new methods. Between 1867 and 1900, U.S. steel production grew more than 500 times. By 1897, American steel rails were cheaper than British ones. The tariff had helped the industry become competitive. Then, the U.S. steel industry started selling steel to England. During World War I, the largest American steel company, U.S. Steel, made more steel than Germany and Austria-Hungary combined.

Republicans were good at making complex deals. This meant that in each area they represented, more people were happy with the tariffs than unhappy. After 1880, the tariff became more of an old idea than an economic need.

Cleveland's Tariff Policy

In 1887, Democratic President Grover Cleveland attacked tariffs. He said they were corrupt and unfair. He argued that high tariffs were an "extortion" and a "betrayal of American fairness." The 1888 election was mainly about tariffs, and Cleveland lost. Republican William McKinley said that free trade gave money and jobs to other nations. He argued that protectionism kept money and jobs at home for Americans.

Democrats campaigned against the high McKinley Tariff of 1890. They won many seats and put Cleveland back in the White House in 1892. But a severe economic downturn in 1893 split the Democratic party. Cleveland wanted much lower tariffs. But many Democrats from industrial areas wanted to keep tariffs high. The Wilson–Gorman Tariff Act of 1894 did lower rates, but it still had many protectionist parts. Cleveland refused to sign it.

McKinley's Tariff Policy

McKinley ran for president in 1896 promising that high tariffs would end the economic downturn. He won a big victory. Republicans quickly passed the Dingley Tariff in 1897, raising rates back to 50%. Democrats said high rates created monopolies and higher prices for consumers. McKinley won reelection easily. He then started talking about trade agreements where countries would lower tariffs for each other. But this idea didn't go anywhere yet.

The Republican Party split over the Payne–Aldrich Tariff of 1909. President Theodore Roosevelt (1901–1909) saw that tariffs were dividing his party. So, he avoided the issue. But under Republican William Howard Taft, the issue exploded. Taft campaigned in 1908 for tariff "reform," which people thought meant lower rates. The House lowered rates, but the Senate, led by Nelson Aldrich, raised them again. Aldrich was a businessman who understood tariffs well. The Midwestern Republicans, who were lawyers, thought tariffs were "sheer robbery."

The Payne–Aldrich Tariff Act of 1909 lowered protection on Midwestern farm products. But it raised rates that helped Aldrich's Northeast. This made the Midwestern Republicans feel tricked. This split led to a big division in the Republican Party in 1912.

By 1913, a new income tax was bringing in money. Democrats in Congress were able to lower tariffs with the Underwood Tariff. But World War I started in 1914. This made tariffs much less important. When Republicans came back to power, they raised rates again with the Fordney–McCumber Tariff of 1922. The next big increase was the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, at the start of the Great Depression.

Tariffs with Canada

The Canadian–American Reciprocity Treaty increased trade between 1855 and 1866. When it ended, Canada started using tariffs. Canada's "National Policy" in 1879 used high tariffs to protect its factories.

Efforts to bring back free trade with Canada failed in 1911. Canada feared American influence. Taft tried to make a trade agreement with Canada that would lower tariffs. Democrats supported it, but Midwestern Republicans were against it. Taft said that North American economies would naturally become more connected. This angered Canadians who wanted to stay close to Britain. Canada's Conservative Party won the election and rejected the agreement.

From 1913 to Today

Woodrow Wilson wanted to lower tariffs a lot when he became president. The Underwood Tariff of 1913 cut rates. But World War I changed trade patterns. Also, the new federal income tax (started in 1913) made tariffs less important for government money.

The Wilson administration also created the Federal Reserve Act in 1913. This centralized the banking system. The income tax and the Federal Reserve changed how the government got its money.

When Republicans returned to power after the war, they brought back high tariffs with the Fordney–McCumber Tariff of 1922. When the Great Depression hit, international trade dropped sharply. The government tried to raise tariffs again with the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act of 1930. But other countries responded with their own tariffs. American imports and exports both fell sharply.

Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Dealers promised to lower tariffs with other countries. They hoped this would increase foreign trade. But it didn't. By 1936, tariffs were not a big political issue anymore. During World War II, trade was mostly handled through special programs like Lend-Lease.

Tariffs and the Great Depression

Most economists believe that the Smoot-Hawley tariff of 1930 did not cause the Great Depression. Many think it only had a very small effect. Some argue that trade was only a small part of the world economy. So, tariffs couldn't have caused such a huge drop in economic activity.

Some economists even think tariffs were helpful. They say tariffs protected local demand from falling prices and outside problems. They point out that local production fell faster than international trade. This suggests that the decline in trade was a result of the Depression, not the cause.

Making Trade Easier

Before 1934, Congress set tariffs after many discussions. In 1934, Congress gave the president power to negotiate tariff reductions with other countries. The idea was that easier trade could help the economy grow.

Between 1934 and 1945, the U.S. made over 32 trade agreements. The belief that low tariffs lead to a richer country is now very common. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), created in 1947, aimed to reduce tariffs worldwide. In 1995, GATT became the World Trade Organization (WTO). This group helps set fair tariff rates for everyone.

Today, only about 30% of goods imported into the U.S. have tariffs. The average tariffs charged by the U.S. are at a very low level.

After World War II

After World War II, U.S. industry and workers did very well. But after 1970, things got harder. There was strong competition from countries with lower production costs. Many industries, like steel, TVs, shoes, and textiles, struggled. Japanese car companies like Toyota and Nissan started to compete with American car makers.

In the late 1970s, Detroit and car worker unions fought for protection. They got "voluntary restrictions" on imports from Japan. These limits had a similar effect to high tariffs. But they didn't cause other countries to retaliate. By limiting the number of cars, these rules actually pushed Japanese companies to make bigger, more expensive cars. This challenged American car makers.

Other agreements were made with countries like Japan, South Korea, and European nations. These agreements limited imports of textiles, steel, electronics, and other goods.

The "chicken tax" was a special tariff from 1964. President Lyndon B. Johnson put a 25% tax on imported light trucks. This was a response to Germany taxing U.S. chicken imports. It also helped President Johnson get support from a major auto workers union.

From the 1980s to Today

During the Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush presidencies, Republicans stopped supporting protectionism. They favored low trade barriers. Free trade with Canada started in 1987. This led to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994. NAFTA aimed to create a larger market for American businesses in Canada and Mexico. President Bill Clinton, with Republican help, passed NAFTA in 1993. This happened despite strong opposition from labor unions.

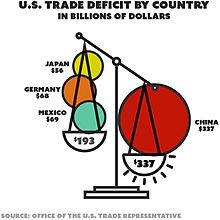

In 2000, Clinton also worked with Republicans to allow China into the WTO. This gave China "most favored nation" trading status. This meant China got the same low tariffs as other WTO members. Supporters of NAFTA and the WTO believed free trade would bring lower prices for consumers.

However, labor unions opposed free trade. They argued it meant lower wages and fewer jobs for American workers. These unions had less political power and often lost these debates.

Studies show that people's economic struggles can make them support protectionism. For example, Donald Trump received strong support in the "Rust Belt" (areas with old factories) in the 2016 election. However, other studies suggest that support for protectionism is more about politics than personal finances.

Even with overall lower international tariffs, some tariffs have been harder to change. For instance, U.S. farm subsidies have not decreased much. This is partly due to tariffs from Europe.

Leaders Who Supported Protectionism

From 1871 to 1913, the average U.S. tariff was never below 38%. During this time, the U.S. economy grew very fast. One expert noted that it grew twice as fast as Britain's.

In 1896, the Republican Party promised to support protectionism. They called it the "stronghold of American industrial independence." They said it taxed foreign goods and helped home industries. They believed it secured the American market for American producers and supported American wages.

George Washington's View

President George Washington said he only used American-made products. He believed they were "of an excellent quality."

One of the first laws he signed was a tariff to "encourage and protect manufactures." In 1790, Washington said that for national security, the U.S. should make its own goods. This would make the country "independent of others for essential, particularly military, supplies."

Thomas Jefferson's Evolving Views

President Thomas Jefferson once wrote that economic ideas can change over time. He said that "no one axiom can be laid down as wise and expedient for all times."

After the War of 1812, Jefferson's views became more like Washington's. He believed some protection was needed for the nation's independence. He said, "manufactures are now as necessary to our independence as to our comfort."

Henry Clay's "American System"

In 1832, Senator Henry Clay said that "free trade" was really just the "British colonial system." He warned that if it succeeded, it would make the U.S. like a colony again.

Clay said that true free trade should be "fair, equal and reciprocal." He believed this kind of trade "never has existed; it never will exist." He warned against buying foreign goods without thinking about American industry.

Andrew Jackson's Support

President Andrew Jackson, a rival of Clay, also supported tariffs. He said, "It is time we should become a little more Americanized." He believed the U.S. should feed its own workers instead of Europe's.

James Monroe's Thoughts

In 1822, President James Monroe said that "unrestricted commerce" (free trade) needed conditions that "has never occurred and can not be expected." He felt there were "strong reasons" to support American manufacturing.

Abraham Lincoln's Arguments

President Abraham Lincoln famously said, "Give us a protective tariff and we will have the greatest nation on earth." He warned that abandoning protection would bring "want and ruin among our people."

Lincoln also argued that a tariff would eventually make domestic goods cheaper. He believed that any temporary price increase would go down as American factories made more.

Lincoln saw tariffs as a fair tax. He said the burden fell mostly on "the wealthy and luxurious few" who bought foreign goods. He thought it was less intrusive than other taxes.

William McKinley's Stance

President William McKinley supported tariffs. He rejected the idea that "cheaper is better." He said, "Under free trade the trader is the master and the producer the slave." He believed protectionism helped people and made the country stronger.

McKinley also said, "Buy where you can pay the easiest." He meant that people should buy where labor earns the most. He believed protectionism "elevates the producer." He argued that tariffs made American lives "sweeter and brighter."

Theodore Roosevelt's View

President Theodore Roosevelt believed that protective tariffs helped America's economy grow and industrialize. In 1902, he said that "great prosperity in this country has always come under a protective tariff."

Donald Trump's Policies

Many people have called President Donald Trump's economic policies protectionist. In 2017, he said that other countries make the U.S. pay high tariffs. But the U.S. charges them "nothing, or almost nothing." He said he believed in free trade, but it "also has to be fair trade."

How Globalization Affects the U.S.

Some thinkers believe that globalization has created a gap between rich and poor in the U.S. They say that wealthy people, who can move their money and businesses anywhere, no longer live in the same world as regular citizens.

These "new elites" are like tourists in their own countries. They feel more connected to an international culture. They might not care as much about their own country's problems. Instead of supporting public services, they invest in private schools and security for their own neighborhoods. They have "withdrawn from common life."

This means that political discussions often only involve the powerful. They might lose touch with the problems of everyday people. This can lead to big arguments about issues without real solutions. The working class faces problems like job losses and a shrinking middle class. But the elites are often protected from these issues.

What People Think About Trade

Opinions on trade have changed over time. Recently, people's views often depend on their political party. In 2017, 67% of Democrats thought free trade agreements were good for the U.S. But only 36% of Republicans agreed.

The 2016 election, with Donald Trump's focus on protectionism, marked a shift. Trump voters had a more positive view of protectionism than other Republican voters. However, after the election, support for free trade agreements increased in both parties.

Experts say that public opinion on trade is easily influenced by politicians. This is because trade is a complex issue. So, people often look to their party leaders to form their opinions.

From 2005 to 2018, more Americans started to like NAFTA. In 2018, 48% thought it was good for the U.S., compared to 38% in 2005.

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |